Andrew Violette's hour long Sonata for Guitar, here performed by Daniel Lippel, is one of three recent solo unaccompanied string works, all of which share a neo-Baroque emphasis on counterpoint and formal design.

| # | Audio | Title/Composer(s) | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time | 01:02:34 | ||

| 01 | I. Moderato II. Colorfield | I. Moderato II. Colorfield | 33:02 |

| 02 | I. Intermezzo II. Fuga a 3 voci: Homage to Joaquin Rodrigo III. Chaconne after Britten (Andante) IV. Lullaby | I. Intermezzo II. Fuga a 3 voci: Homage to Joaquin Rodrigo III. Chaconne after Britten (Andante) IV. Lullaby | 29:32 |

Composer, pianist, and organist Andrew Violette is a fascinating figure in New York's musical ecosystem. A former composition student of Elliott Carter and Roger Sessions and counterpoint student of Otto Luening, Violette's journey as an artist has been rich. Through his student days at Julliard steeped in post- war modernism, a period of intense multi-disciplinary collaboration in the downtown New York scene, a several years foray into Benedictine monastic practice, and his eventual return to the New York scene, Violette has constantly sought to remain true to his own instincts and unique voice. His Sonata for Guitar, written in 2007, is part of a series of works he wrote for solo, unaccompanied string instruments, including large scale works for solo violin and solo cello. All three are vast in scope and length, and represent a revisiting of fundamental musical principles from earlier musical eras, particularly from the Baroque. The Sonata for Guitar is inspired by Benjamin Britten's canonic work, Nocturnal after John Dowland op. 70, and is in six movements, all of which flow seamlessly into one another except for a break between the second movement and the third. After an expansive "Moderato" covering wide harmonic ground, the work narrows into a 25 minute "Colorfield" movement, inspired by the mid-century school of abstract American painting. The music meditates on one harmony, subtly shifting accents and syntax to produce similar lines with different semantic and metric meaning. A short and lyrical "Intermezzo" breaks the piece in half, before a three voice fugue whose quick, three note motive pays homage to the music of Joaquin Rodrigo, reminiscent as it is of castanets. The "Chaconne" that follows is the most direct reference to Britten's epic passacaglia that closes the Nocturnal, and a lilting "Lullaby" closes the hour long sonata with a similarly focused treatment of material as the "Colorfield."

- D. Lippel

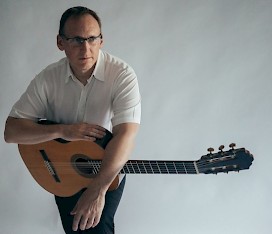

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

My earliest memory is reaching for a ball which faded into the sun. I never did catch the ball but, boy, I really tried. I don't think a day goes by when I don't remember that moment.

Always, when I've started a piece I wanted somehow to attain some sort of perfection--and the great thing is sometimes I get close. But then, once I finish a piece, it's over, it's no longer mine. I lose interest in it and start thinking of the next. I think if I didn't write I'd go crazy.

I was born in Brooklyn in the fifties. I went to High School of Music and Art and learned how to screw, drink and read Hesse. High school was my John Cage period. There was one piece I wrote which had twenty radios going at the same time with different performers running around the theatre--old hat now but fun when you're a teenager.

I studied with Roger Sessions and Elliott Carter when I went to Juilliard. Sessions was like a father to me. He would almost constantly pack tobacco in his pipe but hardly ever smoked. He treated all his students to dinner once a year at a local pasta place.

He would say, "Garlic is sign of civilization." He taught me about the value of the long singing line, the importance of the human voice in music. He trained me to think like a composer. He used simple words in a deep way.

Carter I found difficult. He taught me technical things like the importance of clear notation and the integrity of the line but he was never the warm presence Sessions was, probably because he was old money and I wasn't.

Otto Luening and I spent a wondrous term doing Fux counterpoint exercises.

I had a Master Class with Pierre Boulez that was so publicly humiliating that it strengthened my resolve for the rest of my life. He didn't like some things I did in a piano piece so I took them out.

Ten years later I looked at the piece and realized the things I took out were the only truly original things in the piece. That's when I realized the impossibility of making contemporary judgments about music.

In Juilliard I read Babbitt's writings, the entire Der Reiher of the Darmstadt group, group theory, number theory, explorations of the golden section. Students go through this phase. They write like their teachers. All the poly-rhythms, metronomic modulations, total serialization, hexachordal inversional combinatoriality--it wasn't very original but it was a necessary phase.

I graduated with a Masters and started to knock around NYC as a freelance musician. I invented my own six-note modal system based on the tri-chord and my music started to sound like my own.

Other than a few trips to the MacDowell Colony I had almost no contact with other composers but I did have a lot of contact with dancers and artists and wrote music for a few of them--Paul Sanasardo, Battery Dance. I started to produce my own concerts to good reviews.

Suddenly, in my thirties I felt called to become a contemplative Benedictine monk. It was not a logical decision but the result of a deep inner need.

After a period I left, enriched immeasurably. I had learned various dead languages and Gregorian chant, which the brothers sang seven times as prayer. Chant still permeates my music. Its timeless quality is reflected in my approach to my work.

To me writing is a form of prayer and I, as a composer and musician, am an instrument of God on earth. I have no idea if my writing is good or not but I am sure that, in writing, I am serving the Lord.

http://www.andrewviolette.com/bio.htmI once again find myself in the super-privileged position to be able to be invited to listen to, review and share with you some wonderful music written for our wonderful instrument.

This week I’ve been listening to the very first recording of a work by an American contemporary composer I’ll admit to being completely unfamiliar with, Andrew Violette. This work is his Sonata for Guitar written in 1997 and what an epic it is! The fact that has remained, until now, unrecorded is no slight on the music – it’s a very interesting, well thought out, exploration of harmony and melody. I would imagine it is because it clocks in at just a couple of minutes over the 1 hour mark – that’s a heck of an undertaking for a solo guitarist when we normally see 20 to 25 minutes as a lengthy piece of work!

The guitarist that committed to taking on and recording this mammoth work (and I am so glad that he did) is US guitarist Daniel Lippel. Lippel recorded and released the Sonata through his own label New Focus Recordings (co-founded with compose Peter Gilbert in 2004 to release recordings with maximum creative control). To date Lippel’s recordings have garnered him critical acclaim from Gramophone, American Record Guide, Classical Review of North America, American Record Guide, Guitar Review, Music Web International, Sequenza21, and several other publications.

The Sonata, inspired by the hazy memories of being enthralled by Benjamin Britten’s Nocturnal and making thematic references to that piece, is divided into six movements:

(1) Moderato – setting the melodic and harmonic outlines for the piece. There are some beautiful melodic lines in this movement, some beautiful musical shapes, that I could imagine singing. Rhythmically, like the rest of movements in the piece, this is very straightforward with the interest very much coming from the melodic shapes and treatment of the harmonies – a harmonic rhythm if you will – and interweaving of lines.

(2) Colorfield – my joint favourite of the movements, which surprised me when I read that it was all based on the one harmony. 25 minutes of the one harmony. “Hmmm interesting” I thought and interesting listening it certainly is. This is all about meditating on one musical colour, really understanding and getting to grips with what can be achieved with just one part of the palette, a true musical exploration. In Violette’s words it makes use of “subtly shifting accents and syntax to produce similar lines with different semantic and metric meaning“. Spellbinding.

(3) Intermezzo – This lush and beguiling little Intermezzo opens the second half of the sonata and re-introduces harmonic movement, which is gently refreshing on the ear following the hypnotic harmony of the Colourfield, before moving on quickly into the Fuga.

(4) Fuga a 3 voci: Homage to Joaquin Rodrigo – my other joint favourite movement. We still hear the same harmonic and melodic themes here, but the Spanish elements reminiscent of Rodrigo add a spicy flavour and new aural twist to material we’ve experienced to date. A really nice nod to the type of material that sits so well on the instrument too. Possibly the most guitaristic of the movements.

(5) Chaconne after Britten (Andante) – The penultimate movement references the Passcaglia from Britten’s Nocturnal, and makes use of some very beautiful melodic lines that sing so well on the guitar. Actually I retract my statement above about the Fuga being the most guitaristic of the movements – this is highly guitaristic music and would have to be next in line in order of preference of the movements. Wonderful stuff.

(6) Lullaby – I love the hypnotic feel of the descending thematic material with supporting background arpeggios, and final ascending and descnding harmonics lulling you into a dream world, in a spellbinding fashion reminiscent of the Colourfield. A wonderful way to end the piece.

Just one tiny thing mars the recording a little for me – I think perhaps also having each movement of the Sonata as a separate track , for me personally, would allow a great accessibility to the piece and explore each movement in isolation. Just a suggestion however, but perhaps not what Lippel nor Violette intended for the listener. In that case, perhaps time indications of where each movement begins?

Anyway, this is all just very minor stuff and these things aside this is a simply marvellous demonstration of some masterful playing, sensitive to the subtle nuances of the music wending and winding its way, developing over time through the various movements. It is also a marvellous recorded debut of what is a fantastic (and epic!) piece of the modern repertoire that undoubtedly deserves to be heard far and wide. Hats off to both Lippel and Violette!

Be sure to check it out for yourself. Head on over to the New Focus Recordings website where you can download the album for the very low price of just USD$8.99 – a bargain!

This album presents one piece: an hour long Sonata for Guitar by Andrew Violette. That is quite the undertaking by guitarist Dan Lippel. Just imagine emerging yourself in one piece, not only learning it but also recording it. The determination of both the composer and the guitarist really sparked my interest. New york born composer Andrew Violette studied with Elliott Carter and Roger Sessions and has been quoted as “an unsung maverick among New York composers” (New Yorker).

For this work Violette pays homage to Britten and Bach as well as Rodrigo and explores counterpoint and color while focusing on singable melody. As for the form, as the composer explains, “Why is the piece so long? The piece is long because I’m interested in thematic development. Thematic development takes time. Time I must have to wrench every last inflection from every last motif I put out there. I develop my material the usual classical ways: by counterpoint, texture, harmony and over-all form.” The result is a tapestry of expansive movements that curiously keep you listening. Some general listeners may zone-out but I suggest giving the work a careful but relaxed listen and let the composition take you on a thematic ride (if you have an hour to spare!).

The recording breaks the Sonata into two tracks: Track 1 (33:02), I. Moderato, II. Colorfield and Track 2 (29:32), I. Intermezzo, II. Fuga a 3 voci: Homage to Joaquin Rodrigo, III. Chaconne after Britten (Andante), IV. Lullaby. The music is thick with counterpoint yet singable as the composer suggests. I’m not sure who I would compare it to, maybe Hans Werner Henze and Britten if I had to make a comparison but Violette is more expansive and freer in form and language than Henze. Here’s a little synopsis of the work by New Focus:

After an expansive “Moderato” covering wide harmonic ground, the work narrows into a 25 minute “Colorfield” movement, inspired by the mid-century school of abstract American painting. The music meditates on one harmony, subtly shifting accents and syntax to produce similar lines with different semantic and metric meaning. A short and lyrical “Intermezzo” breaks the piece in half, before a three voice fugue whose quick, three note motive pays homage to the music of Joaquin Rodrigo, reminiscent as it is of castanets. The “Chaconne” that follows is the most direct reference to Britten’s epic passacaglia that closes the Nocturnal, and a lilting “Lullaby” closes the hour long sonata with a similarly focused treatment of material as the “Colorfield.”

The guitar playing is impressive mainly for Lippel’s focus and rhythmic drive due to the massive scope of the work. The piece does not let up in terms of playing. There is little in the way of guitar effects or fluffy textures. The first track is straight forward playing of notes in a texture of counterpoint and continuous movement which Lippel executes with focus and determination. The second track has moments of more space and variety in texture. Lippel also showcases some excellent motivic clarity and some pleasant coloristic touches.

Recording quality is good overall. It’s a bit on the ‘live’ side but I somewhat prefer that to the modern beefy sound of close mics. Regardless, it sounds like you are sitting close by in reverberant room and all the colors as well as articulations of the guitar are clear.

A huge undertaking by composer and guitarist! Andrew Violette’s work is impressively realized by Dan Lippel’s determined and focused guitar performance. From expansive movements thick with counterpoint to singable melodic work there is something for everyone in this modern but relatable work. Not to be overlooked.

- Bradford Werner, 10/21/2014

Essay on Violette's work including an analysis of the Guitar Sonata

http://www.furious.com/perfect/andrewviolette.html

— Daniel Barbiero, 12.03.2021