Composer and Rome Prize winner Christopher Trapani releases Horizontal Drift, a collection of six works written for custom instruments that explore rich corners of microtonal tuning, timbre, and electronic processing. Featuring performers Maximilian Haft, Daniel Lippel, Amy Advocat, Marilyn Nonken, and Marco Fusi in music for vioara cu goarna ("violin with horn"), quarter-tone guitar, Bohlen-Pierce clarinet, piano scordatura, Midi-controlled Fokker organ, and viola d'amore, Trapani revels in sound worlds that challenge listener expectations and reveal new expressive possibilities.

| # | Audio | Title/Composer(s) | Performer(s) | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time | 59:00 | |||

| 01 | Târgul | Târgul | Maximilian Haft, vioara cu goarna, Christopher Trapani, electronics | 10:03 |

| 02 | Horizontal Drift | Horizontal Drift | Daniel Lippel, quarter-tone guitar, Christopher Trapani, electronics | 12:20 |

| 03 | Linear A | Linear A | Amy Advocat, Bohlen-Pierce clarinet, Christopher Trapani, electronics | 7:37 |

Lost Time Triptych |

||||

| Marilyn Nonken, piano scordatura | ||||

| 04 | I. Time is a Jet Plane | I. Time is a Jet Plane | 0:32 | |

| 05 | II. Time is Piling Up | II. Time is Piling Up | 2:08 | |

| 06 | III. Time is Beginning to Crawl | III. Time is Beginning to Crawl | 4:52 | |

| 07 | Forty-Nine, Forty-Nine | Forty-Nine, Forty-Nine | Christopher Trapani, electronics | 5:27 |

| 08 | Tesseræ | Tesseræ | Marco Fusi, viola d’amore, Christopher Trapani, electronics | 16:01 |

One of the consistent strains in Christopher Trapani’s work is his attraction to what one might call the archeology of sonic exploration. His interest in diverse music cultures as fertile territory to explore microtonality, timbre, and rhythm frees his music to pursue an essential expression beyond the conventional confines of concert composition. The works on Horizontal Drift zero in on this component of Trapani’s work, focusing on music he has written for unconventional instruments, some custom-made, others part of folkloric traditions typically found away from the concert stage. With the unique characteristics of these instruments as a frame, Trapani delves into a variety of tuning systems, from alternate fixed temperaments to just intonation, as well as a range of applications for electronics.

The opening work on the recording, Tārgul, is composed for the vioara cu goarna (“violin with horn” in Romanian), an instrument modeled after the stroh violin which was designed to help string instruments project for early recording technology. The vioara cu goarna has an edgy, brash sound; Trapani leans into its characteristic its clarion call, peppering Tārgul with unsettling short glissandi, sighing gestures, dry pizzicati, and angular riffs. The electronics are played through megaphones at the sides of the stage, imitating the brittle timbral quality of the instrument.

The title track is written for quarter-tone guitar and a Max module called the LoopSculptor which allows real-time manipulation of passages across several parameters. Trapani writes that the work was inspired by his hometown of New Orleans – indeed its languorous quality evokes the heavy, humid heat of the Delta and the paradox between the city’s timeless inertia and its constantly shifting topography. Trapani deconstructs some characteristic Delta blues guitar gestures – particularly grace note slides and hammer ons – to construct an otherworldly meditation enhanced by the quarter-tone pitch language and wafting electronic loops.

Linear A was written for a clarinet tuned to the Bohlen-Pierce scale, a microtonal system that repeats at the twelfth instead of the octave. Like the title track, the electronics are oriented around loops that manipulate the material played by the live performer. The instrumental material in Linear A exhibits a wide range from subdued to virtuosic, inward to extroverted. The flexibility of Trapani’s live electronics patch allows him to animate a soundscape with voices that create the illusion of independence, despite being generated from the same live sound source. This veneer of independence stands out even more so in relief when the final passage of the piece emerges, a four voice chorale harmonizing a wistful melody.

Lost Time Triptych was written as a companion piece to Gérard Grisey’s Vortex Temporum for piano scordatura, in which four pitches are detuned by a quarter-tone. The three movements of the piece, each with subtitles borrowed from Bob Dylan, examine three different temporal relationships in music that Grisey termed “the subjective layers of time.” The first is compressed, containing angular, stabbing chords. The second unfolds in “real” time, echoing the motivic play heard in Horizontal Drift, and ending abruptly. The third and final movement is spacious and resonant, inviting the listener to journey inside the exotic sonorities resultant from the detuned pitches.

Forty-Nine, Forty-Nine is the only work on the recording not performed by a human, though it is not strictly an electronic piece either. Instead, it’s a player organ piece, the 31 equal tempered Fokker organ to be specific, as controlled by a program called Open Music sending marching orders via Midi. Forty Nine, Forty Nine takes the deepest dive into microtonal theory on the album, organizing the work around highlighting the just intervals that the 31 EDO tuning system best approximates. The piece is dramatic and bracing, and evokes Nancarrow in its mechanical virtuosity.

Tessaræ returns to the bowed string sound world of Tārgul, this time featuring the viola d’amore, a unique instrument in the Western concert tradition due to its sympathetic strings. Trapani explores connections with bowed string instruments with sympathetic strings in other cultures in a work that engages with traditional music more than the other music on the album. Though no specific stylistic restrictions are adhered to, we hear allusions to the drone textures and unfolding melodic exploration of Indian music as well as Turkish music, and a general restrained gestural vocabulary that conjures ritual music’s patient pace of development.

– Dan Lippel

Produced by Christopher Trapani

Engineer: Ryan Streber (track 2) / Paul Geluso (tracks 4-6) / Camille Giuglaris (track 8) / Christopher Trapani (tracks 1, 3, 7)

Târgul recorded March 11, 2019 (Austin, TX)

Horizontal Drift recorded October 29, 2020 at Oktaven Audio (Mount Vernon, NY)

Linear A recorded May 14, 2021 (Providence, RI)

Lost Time Triptych recorded November 1, 2020 at James Dolan Music Recording Studio, NYU (New York, NY)

Forty-Nine, Forty-Nine recorded September 2, 2012 at Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ (Amsterdam, NL) Tesseræ recorded March 29-30, 2018 at CIRM (Nice, France)

Support for this CD has been graciously provided by the Alice M. Ditson Fund, a YoungArts Microgrant, and by the generous supporters of a Kickstarter campaign.

Thanks to: Ryan Streber, Daniel Lippel, Juuso Nieminen, François Paris, Camille Giuglaris, Ross Daly, Joël Bons, Diemo Schwarz, Sander Germanus, Jackie Delamatre, Ben Cooper, Maximilian Haft, Serge Vuille, David Poissonnier, Giuliano Bracci, Jean Bresson, Daniele Ghisi, Andrea Agostini, Marco Fusi, Rick Whitaker, Marilyn Nonken, Turgut Erçetin, Esin Pektaş

CD design and layout by Chazwald Jones (New Orleans, LA)

All photos © Christopher Trapani, 2022 except page 2 photo by Katerina Duda

Winner of the 2016-17 Luciano Berio Rome Prize, Christopher Trapani is a composer with a genuine international trajectory. He maintains an active career in the United States, in the UK, and in Continental Europe. Commissions have come from the BBC, the JACK Quartet, Ensemble Modern, and Radio France, and his works have been heard at Carnegie Hall, the Venice Biennale, Southbank Centre, Ruhrtriennale, IRCAM, Ravenna Festival, and Wigmore Hall.

Christopher’s music weaves American and European stylistic strands into an organic personal aesthetic that defies easy classification. Snippets of Delta Blues, dance band foxtrots, Appalachian folk, and Turkish makam can be heard alongside spectral swells and meandering canons. As in Christopher’s hometown of New Orleans, diverse traditions coexist and intermingle, swirled into a rich melting pot.

Christopher Trapani was born in New Orleans, Louisiana (USA). He earned a Bachelor’s degree from Harvard, then spent most of his twenties overseas: a year in London, working on a Master’s degree at the Royal College of Music with Julian Anderson; a year in Istanbul, studying microtonality in Ottoman music on a Fulbright grant; and seven years in Paris, where he studied with Philippe Leroux and worked at IRCAM with Yan Maresz. Since 2010, Christopher has lived in New York City, where he earned a doctorate at Columbia University, working with Tristan Murail, George Lewis, Georg Friedrich Haas, and Fred Lerdahl.

Christopher is the winner of the 2007 Gaudeamus Prize, as well as awards from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, ASCAP, and BMI, along with fellowships from Schloss Solitude and the Camargo Foundation. His scores have been performed by ICTUS, Yarn/Wire, ZWERM, Ekmeles, the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, and the Spektral Quartet, amongst others.

http://www.christophertrapani.comBelgian-American violinist Maximilian Haft resides in Geneva, Switzerland and has lived in Europe since 2009. A multifaceted musician, Max specializes in contemporary repertoire and improvisation. He has performed across Europe, North America, South America, and the Middle East in formal concert settings, theatrical contexts, and spatial installations. As a soloist, Max has performed and premiered contemporary violin concertos with the North Netherlands Symphony Orchestra, The Geneva Chamber Orchestra, Collegium Novum Zurich, and the Kiev Symphony Orchestra. In Switzerland, Max has held the position of violin solo with Ensemble Contrechamps since 2015 and is a founding member of Ensemble Proton Bern. Max has a Bachelor’s in Violin Performance from the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston where he studied with Masuko Ushioda†, and a Master’s degree cum laude from the Royal Conservatory of The Hague, having studied there with Vera Beths. He is a native of Sacramento California, where he returns in the summer to teach chamber music to young aspiring musicians of his former youth symphony and as a performer with the Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music Orchestra in Santa Cruz.

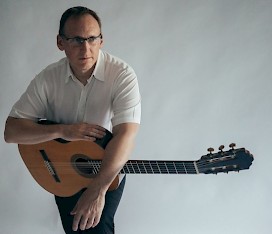

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

Sought out for her “dazzling” (Boston Globe) performances with “extreme control and beauty” (The Clarinet Journal), Dr. Amy Advocat has performed with Alarm Will Sound, Boston Modern Orchestra Project, Sound Icon, Guerilla Opera, Firebird Ensemble, Callithumpian Consort, Collage New Music, Dinosaur Annex, and The New Fromm Players. She is a founding member of the duo Transient Canvas, who have released three critically acclaimed albums on New Focus and have toured internationally, including performances at New Music Gathering, Red Note Festival, Alba Music Festival. Their second album, Wired, was praised as “an eloquent testament to the versatile imagination they both display and inspire in others” by the San Francisco Chronicle, and their third, Right now, in a second was named a top local album of 2020 by the Boston Globe. Dr. Advocat is a proud endorsing artist with Conn-Semer and Henri Selmer Paris.

Marilyn Nonken is one of the most celebrated champions of the modern repertoire of her generation, known for performances that explore transcendent virtuosity and extremes of musical expression. Upon her 1993 New York debut, she was heralded as "a determined protector of important music" (New York Times). Recognized a "one of the greatest interpreters of new music" (American Record Guide), she has been named "Best of the Year" by some of the nation's leading critics.

Marilyn Nonken's performances have been presented at such venues as Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Miller Theatre, the Guggenheim Museum, (Le) Poisson Rouge, IRCAM and the Théâtre Bouffe du Nord (Paris), the ABC (Melbourne), Instituto-Norteamericano (Santiago), the Music Gallery (Toronto), the Phillips Collection, and the Menil Collection, as well as conservatories and universities around the world. Festival appearances include Résonances and the Festival d'Automne 4both, Paris) and When Morty Met John, Making Music, and Works and Process (all, New York), American Sublime (Philadelphia), The Festival of New American Music (Sacramento), Musica Nova (Helsinki), Aspects des Musiques d'Aujourd-hui (Caen), Messiaen 2008 (Birmingham, UK), New Music Days (Ostrava), Musikhøst (Odense), Music on the Edge (Pittsburgh), Piano Festival Northwest (Portland), and the William Kapell International Piano Festival and Competition. Highlights of recent seasons have included performances of Hugues Dufourt's Erlkönig, Morton Feldman'sTriadic Memories,Tristan Murai's complete piano music, and Olivier Messiae's "Visions de'l Amen" with Sarah Rothenberg. Composers who have written for her include Milton Babbitt, Drew Baker, Pascal Dusapin, Jason Eckardt, Michael Finnissy, Joshua Fineberg, Liza Lim, and Tristan Murail.

She has recorded for New World Records, Mode, Lovely Music, Albany, Metier, Divine Art, Innova, CRI, BMOP Sound, New Focus, Cairos, Tzadik, and Bridge. Her solo discs include "American Spiritual," a CD of works written for her, “Morton Feldman: Triadic Memories,” “Tristan Murail: The Complete Piano Music,” “Stress Position: The Complete Piano Music of Drew Baker," and "Voix Voilees," music of Joshua Fineberg and Hugues Dufourt. She appears as concerto soloist in David Rakowski's Piano Concerto (Gil Rose and the Boston Modern Orchestra Project), Roger Reynolds's “The Angel of Death (Magnus Martensson and the Slee Sinfonietta), and Jason Eckardt's "Trespass" (Timothy Weiss and the Oberlin Contemporary Music Ensemble).

A student of David Burge at the Eastman School, Marilyn Nonken received a Ph.D. degree in musicology from Columbia University. Her writings on music have been published in Tempo, Perspectives of New Music, Contemporary Music Review, Agni, Current Musicology, Ecological Psychology, and the Journal of the Institute for Studies in American Music. She has contributed chapters to “Perspectives on French Piano Music” and “Messiaen Perspectives 2: Techniques, Influence, and Reception” (both, Ashgate) and is currently writing a monograph on spectral piano music for Cambridge University Press. Director of Piano Studies at New York University's Steinhardt School, Marilyn Nonken is a Steinway Artist.

http://www.marilynnonken.com/Marco Fusi is a violinist/violist, and a passionate advocate for the music of our time. Among many collaborations with emerging and established composers, he has premiered works by Billone, Sciarrino, Eötvös, Cendo and Ferneyhough. Marco has performed with Pierre Boulez, Lorin Maazel, Alan Gilbert, Beat Furrer, David Robertson, and frequently plays with leading contemporary ensembles including Klangforum Wien, MusikFabrik, Meitar Ensemble, Mivos Quartet, Ensemble Linea, Interface (Frankfurt), Phoenix (Basel) and Handwerk (Köln); Marco has recorded several solo albums, published by Kairos, Stradivarius, Col Legno, Da Vinci, Geiger Grammofon. Marco also plays viola d’amore, commissioning new pieces and collaborating with composers to promote and expand existing repertoire for the instrument. A strong advocate and educator of contemporary music, Marco teaches Contemporary Chamber Music at the Milano conservatory “G. Verdi” and is currently Researcher in Performance at the Royal Conservatoire of Antwerp.

Other than his name and email, the only thing on multiple-award-winning American/Italian composer Christopher Trapani’s business card is, “Mandolins and Microtones.” Both interests are reflected in the outstanding album, Horizontal Drift, featuring six of his compositions.

Trapani’s bespoke compositional approach taps the soundworlds of American, European, Middle Eastern and South Asian origin, blending them into his own musical palette. Certainly ambitious in its cultural diversity, Turkish maqam and South Asian raga rub shoulders with Delta blues, Appalachian folk and 20th-century-influenced electronically mediated spectral effects and canons. Horizontal Drift also reflects Trapani’s preoccupation with melody couched in microtonality and just intonation. Timbral diversity derived from the use of unusual instruments, retuning and preparation are other compositional leitmotifs.

Album opener Târgul (the name of a Romanian river) is scored for the Romanian horn-violin plus electronics. With a metal resonator and amplifying horn, it has a tinny, thin sound reminiscent of a 1900s cylinder violin recording. Trapani’s intriguing composition maps a modern musical vocabulary onto the instrument’s keening voice, his work interrogating its roots in the folk music of the Bihor region of Romania.

The track Tesserae features the viola d’amore, a Baroque-era six- or seven-stringed bowed instrument sporting sympathetic strings. After exploring multi-tonally inflected modal melodies with gliding ornaments, well into the piece Trapani engineers the musical analogy of a coup de théâtre. In Marco Fusi’s skillful and sensitive hands the viola d’amore unexpectedly morphs into a very convincing Hindustani sarangi. This magical moment of musical metamorphosis was so satisfying I had to play it several times.

— Andrew Timar, 7.04.2022

Really Coming Down, composition for electric guitar and live electronics from 2007, caused a rather important change in the artistic life of Christopher Trapani (1980), for several reasons. It is the first piece in which Trapani comes into contact with the aids of electronic composition; it is the first act of connection to the electric guitar, one of the most studied and rationally loved instruments by the composer; it constitutes the auspicious entry into the maze of the discoveries of microtonality; it expresses the full awareness of a musical journey made around the world, whose slags serve to constitute a tremendously unique compositional view, in which the traditions, rhythms and poetics of a place become part of the compositional material on which to act. Trapani comes from New Orleans but in reality he is a citizen of the world who mulls over the history of music and on some of the aspects that founded it and Really Coming Down is only the gateway to definitively settle his personality in the music that counts. The overall calibration of musical parameters leads to the foundation of a very personal concept of "consonance", which implies the partial dissociation of the instrument from its historical context: Trapani will explain this concept very well in Cognitive Consonance, a composition written a couple of years later after Really Coming Down, where he used a qanun, a 78-stringed instrument of the Arab tradition, and a hexaphonic electric guitar that at the time of creation exploited the innovation of selective pick-ups, able to feed into a separate channel managed by a software the signal of each string of the instrument; in the program notes of Cognitive Consonance Trapani states that:

"...Cognitive Consonance [is] internal harmony obtained by the reconciliation of two ideas initially perceived as contradictory...[...] is a manifesto for "cognitive" music (provoking thought; engaging the faculties of association and memory) as well as "consonant" (a notion whose expansion and redefinition will be the common thread of the a priori disjoint stages of the journey)...".

Trapani's sources of inspiration are transparent: the composer loves quodiblets, uses microtonality to modify the contexts in which the instruments have historically been recognized by the community of listeners (dissociation passes through any type of instrument used) and tries to establish new thought relationships through a new concept of musical consonance that derives from intervals and scordaturas: we recognize the "seeds" of a theme, of a timbre, or we recognize the selective uses made of instruments but the whole composition is compacted into new results obtained from navigation through micro intervals.

Trapani's research on unusual instruments and intonations treated with the use of electronic resources has been carried forward quickly in the last 10 years, often also supported by a targeted literary inspiration, but what is striking is the idiosyncratic possession of the elements and their reconversion into a renewed material: it would be utopian to make stylistic juxtapositions to people like Partch, Radulescu or Lang, just as it would be madness to think of an uncritical mixture of the musical combinations he created, without finding a personal definition of the musical objectives, a reason for them to exist; scordaturas, loops, delays and digital syntheses capable of influencing the characteristics of the instruments used, are variables that Trapani creates as a consequence of an intricate poetics, where it is difficult to find the classic reassurance of music. In Trapani there is no particular interest in the use of extended techniques or noise, a theoretical mediation that in most cases leads to a spasmodic exploration of the instruments in a compositional key, but a mere exploitation of the possibilities of those resources, that aims to provoke an emotional state: it is from here that his research develops, all attempts to find new transversal and careless sounds, perfectly suited to a state of tension or confusion, loneliness or detachment, a "researcher" of a color very different from that expressed by an impressionist or a music spectralist, conceived with microtonal tuning, which in turn is not a static or dronistic entity, but a multiplicative path of polyphonies.

2022 brings us a new CD published for New Focus Recordings, consisting of 6 compositions written between 2011 and 2021: Horizontal Drift offers another efficient overview of the research scenarios undertaken by Trapani, in the direction of the creation of possible cognitive consonances.

Târgul, is played on the vioara cu goarna, a violin where the acoustic body is replaced by a metal resonator joined to the bell of a horn. It is an instrument that is played above all in the north of Romania and which has obviously fascinated Trapani, who went to those places to obtain a perfect sense of it: he works on melodic hints, on pizzicato and on fragments of sound, with a part of electronics that create "movement", duplicative or spatial relations eviscerated in a special timbre, that of two megaphones; in the end the place is also revealed, when Negreni's field recording of the market appears. The piece is performed by Maximilian Haft, a violinist who seems to have had the same instinct as Trapani in finding charm and satisfaction in this traditional Eastern European instrument.

Horizontal Drift is the investigation of the acoustic guitar tuned in quarter tones. The guitarist produces notes and chords without a reference to dynamics, but measures himself with echoes and altered duplications of his work, loops and transpositions through software in a climate that incorporates "sliding", an effect that Trapani sensed in the compositional and practical development to express his emotional point of view on the terrible events of the floods in New Orleans. Although commissioned by Juuso Nieminen, the version we hear here is by Daniel Lippel, which gives us a lot of cognitive details.

Linear A is for solo clarinet, tuned according to the microtonal Bohlen-Pierce scale of 13 semitones, plus electronics. It is a question of evoking spiral pictograms of antiquity (the writing systems of the Minoan civilization) and even here the loops lend themselves very well to enrich the vaulting of the clarinet, definitely capable of creating a second part of equal importance. The score is entrusted to Amy Advocat and highlights Trapani's investigation into the harmonic realities of the Bohlen-Pierce clarinet which allows the performer to find harmonic turns not possible in the traditional 12-tone scale.

Lost Time Triptych, on the other hand, is the only piece without electronics and entrusted to pianist Marilyn Nonken, with whom Trapani has studied the possibilities of an emulation of the sound tempos proposed by Gérard Grisey in his Vortex Temporum through a particular scordatura of the piano, four notes of the octave changed to a quarter of their normal pitch. According to Grisey, time presents itself in three modalities, a current form which is time marked by the events of humans and two opposite forms, time dilated and time contracted, scans that Grisey carried in his theory from the animal kingdom (whales or insects for example) and that Trapani transfers to the piano through some targeted structures capable of enhancing the perception of differences.

Forty-nine, forty-nine is a composition on the Fokker organ, a 31-tone microtonal organ created by Adriaan Fokker on the instructions of the Dutch physicist Huygens: the organ is located at the Muziekgebouw aan't IJ, a building on the Amstel in Amsterdam which has become the place par excellence for contemporary music concerts (the Bimhuis of jazz, just to understand). The piece is short and very idiosyncratic, the Fokker organ has an anomalous keyboard made with stepped keys that support microtonal scales and a further innovation is used, an intelligent midi interface connected to an external computer.

Tesseræ, on the other hand, is designed for the viola d'amore and is the result of a collaboration with Marco Fusi. The title imposes a clear reference to the set of frequencies combed through on an instrument, but there is something more in the piece, a comparison of the viola d'amore with other traditional instruments (the kemence, the sarangi, the lira) in sympathetic terms. The score plays on the perspective of long microtonal introspections that perturb the waters, making us think of a West and an East placed in union or in immediate temporal succession, with electronics that expand the sounds; some strings of the viola d'amore are prepared with tinfoil so that the hum brings confluences, while a special wooden mute is used to make the sound of the instrument more obscure and elusive. Trapani's skill lies in having welcomed Fusi's meticulous experiments on the viola d'amore and in having shared the expressive details of the sound.

I came into contact with Trapani during his residence in Palermo. A few questions and some explanations are necessary for a conscious and ameliorative listening to Horizontal Drift.

EG: Thank you Christopher for agreeing to talk on Percorsi Musicali. The first thing I would like to ask you is simple and concerns your surname which is typically Italian. Where did your ancestors come from?

CT: My great-great-grandfather was born in Sciacca in 1880, and emigrated to New Orleans in 1896, where my family has stayed ever since. He was the last Italian-born member of my family, but I am the first to reverse the trend: I became an Italian citizen in 2018. I hold dual nationality now, and I would like to be known as both an American and Italian composer.

EG: In my profile I defined you as a "citizen" of the world who mulls over musical history. How true is this statement of mine?

CT: I would certainly like to believe that is true! To dovetail with my answer to the last question: I am proud to be both an American an a European citizen, and of the ways in which my life between two continents has nourished my work. I have also lived in Istanbul, studying microtonal inflections of Ottoman music there, and have taken lessons in Hindustani music from a teacher in Mumbai. The ideas of place, travel, and studying stylistic trends are crucial to me. I feel that my main task as a composer is to synthesize all of these disparate influences, creating new amalgams by recombining sources in a personal way.

EG: Microtonality is a fundamental element of your music. In your opinion, what kind of information can it produce? At its deepest, can there be a spiritual way?

CT: I was drawn to microtones for their immediate, expressive color. Maybe I noticed it first as a guitarist: from early on, I liked bending notes or playing with a slide to get off of the grid of equal temperament. I was aware of the role of microtones in the blues, and when I moved to Paris in 2003, I started to hear them more often in the spectral music I was discovering there. One very influential concert for me was a full performance of Grisey’s Les Espaces Acoustiques, conducted by Pierre-André Valade at the Cité de la Musique in late 2003. I started experimenting with microtones in my own music soon after, first with a piece called Blues Wrapped Around My Head (2004) for four clarinets, one of which is tuned down by a quarter-tone.

In the years that followed, I found myself working with the late French qanûn player Julien Jalâl Eddine Weiss, who had conducted his own personal exploration of microtonality, rooted in the history of Arabic treatises on tuning. Julien certainly believed that there was a spiritual dimension to just intonation, and the piece I wrote for him, Cognitive Consonance, tries to embrace this idea. At heart, it strives to be music that expands the definition of what is consonant, resonant, and harmonious beyond simple ratios, bypassing the dichotomy of consonance/dissonance and luxuriating in microtonal spaces.

EG: What is cognition for you? Can it affect a correct listening?

CT: In short, I look for an intellectually stimulating dimension to any work of music. Admittedly, this is a personal preference: I often find it hard to get lost in repetitive music that does not have some degree of stimulation or change. I hear that other listeners can feel entranced, lulled into a tranquil state by repeated motifs, but not me: I tend to like shorter pieces or music whose surface details are often changing. I have many pieces based on loops, but they are always flexible loops while timing and tuning can change dynamically. I feel I somehow need to have my attention drawn and repeatedly re-focused as a listener, and that’s the experience that I try to replicate for listeners when composing.

EG: In your music there are allusions that come from the entire musical world, with great consideration for traditional musical instruments or for the type of arrangements or creations built into popular and rock music. In Lost Time triptych, for example, there is a reference to Bob Dylan probably referring to his album Time Out of Mind: I understood in any case that you were attracted to the productions of Daniel Lanois. Is it possible to establish a connection between Grisey and Lanois, in your opinion?

CT: Let’s see: “Time is Piling Up” is a line from Dylan’s song “Mississippi,” which was an outtake from Time Out of Mind, and “Time is Beginning to Crawl” comes from the earlier song “Where Teardrops Fall” from Oh Mercy! — so yes, there are allusions to two Daniel Lanois productions. I admire the rich soundscapes that Lanois produces, distant layers overlaid with closer and quicker sounds, always atmospheric and engaging to the ear. In that kind of attention to sonic detail, and in his enveloping, lush sonorities, you could easily see a parallel with Grisey, I believe.

EG: Forty-Nine, Forty-Nine uses the midi-controlled Fokker organ, an eclectic microtonal instrument found in Amsterdam; in the past some Dutch composers have been interested in this instrument (I remember Badings among others). Can you explain better what kind of research did you put into your piece and above all the meaning of the two 49s?

CT: In fact, “4949” was just my street address when I was young. When writing for the Fokker organ, I noticed that with 31 tones to the octave, 49 tones approximated a perfect 12th. Also the low G which opens the piece is 49 Hz. It’s a bit of a numerological game, which is yet another approach I use when working with microtones, especially equidistant divisions: why not try the same kinds of combinatorial tricks that a dodecaphonic composer might? My ears have gotten a little bored of hearing intervallic relationships in twelve-tone music, but in a non-tempered system those games can sound refreshing.

EG: An extraordinary piece is Tesseræ with Marco Fusi on the viola d’amore. There is an incredible detail of harmonics and sounds, the result of a very in-depth study on the sonic consequences of the instrument's microtonal articulations. What was the biggest difficulty of that piece? How did you share the compositional matters with Fusi?

CT: The first idea for Tesserae came after a course that I took with Ross Daly at his Labyrinth workshop in Crete. I was entranced by the sound of the buzzing sympathetic strings on his instruments, the lyra and tarhu — and I immediately thought of how I could replicate those sounds both acoustically, with the viola d’amore, and electronically. I wanted to give myself the constraint of creating a primarily modal composition, a single voice with resonance, occasional forks, and drones, built around the stylistic language of modal traditions. I started by listening with careful attention to my sources: Derya Türkan and İhsan Özgen on the kemençe, Dhruba Ghosh on the sarangi… Then it was a question of how to best notate these gestures, and Marco came up with the idea of using a looser, proportional rhythmic notation, based on a system of Kurtag’s, to capture the meter-less freedom of an alap or taksim. This rhythmic approach gives the piece an organic flow that complements and underpins its wanderings between different modal centers, sonorities, and allusions to various traditions. Aside from the demanding precision of the tuning, which must be very carefully calibrated for the electronics to react properly, Marco also had to absorb the stylistic nuances via a playlist I made for him of the same masters. A lot of work, but the result is astonishing: his beautiful, subtle, and informed performance.

EG: What are you devoting your attention to right now?

CT: At the moment I am composing a song cycle for voice and piano, setting texts from Rebecca Solnit’s wonderful book A Field Guide to Getting Lost. After this, a longer piece for the electric guitar quartet Zwerm and two fantastic singers — Sofia Jernberg and Sophia Burgos — that will premiere in 2023. Beyond that, I am outfitting my studio in Palermo with a piano and some equipment, changing the tubes in my guitar amp and the skin on my tenor banjo, and setting it up for future collaborators with anyone who’d like to work in Sicily!

— Ettore Garzia, 6.14.2022

On the title track of Trapani's latest portrait album, Dan Lippel plays a quarter-tone guitar through software of the composer's own design called LoopSculptor. The piece incorporates tropes from Delta blues and other genres native to Trapani's hometown of New Orleans, resulting in a 10-minute trip through museum of hazy half-memories. The title seems to do double duty, referring both to American expansion and the interactions of various loops across the software's grid layout. The unusual instrument, the engineer's approach to sound, and the emotionally resonant results are paradigmatic of the whole album, which opens with Targul, a piece for vioara cu goarna, a horn-enhanced instrument similar to a Stroh violin. Played with seemingly casual mastery by Maximilian Haft, the sound is not unlike a gramophone, with a sharp, tinny edge that blends perfectly with the sketchy, truncated phrases of the music. Haft also finds himself in a sort of duet/competition with electronics played through megaphones, adding immersive depth to the attenuated sounds. Trapani also puts new-music piano maven Marilyn Nonken through her paces in Lost Time Triptych, a piece for scordatura-tuned instrument that manages to be inspired by both Gerard Grisey and Bob Dylan. The other works, including Linear A, for microtonal clarinet (Amy Advocat) and electronics, Forty-Nine, Forty-Nine, for a MIDI-controlled equal-tempered Fokker organ, and Tesserae, for viola d’amore (Marco Fusi) grab the attention as well. Trapani continues to prove himself to be smart, playful, and fearless explorer on this triumphant collection.

— Jeremy Shatan, 5.28.2022

For the six works on his album Horizontal Drift, composer Christopher Trapani chose an unusual array of instruments capable of producing a soundworld of microtones and extended timbres.

The album opens with a piece for Romanian horn-violin (played by Maximilian Haft), a violin with a metal resonator, and horn used for amplification. Its sound is tinny and thin, like an early 20th-century recording of a violin. Trapani’s writing for it consists of contemporary gestures, but even with the electronics that augment the instrument’s naturally unnatural voice, the piece conserves an echo of the folk milieu in which the horn-violin is usually encountered. Bookending the album is a second piece for bowed string instrument—Tesserae, written for the viola d’amore, a Baroque-era viola notable for its array of sympathetic strings. Trapani eschews an obvious, quasi-Baroque sound for a melody that incorporates gliding ornaments reminiscent of Hindustani vocal music. It’s sensitively played by Marco Fusi.

Three pieces were composed for unconventionally tuned instruments. Linear A, named for the still-undeciphered ancient Minoan script and performed by Amy Advocat, is for clarinet tuned to the 13-step Bohlen-Pierce scale, and live loops—a mechanism that sets in motion a swooping counterpoint of self-replicating melody. The tryptich Lost Time, for scordatura piano (played by Marilyn Nonken) is a kind of dialogue between Bob Dylan, whose lyrics provide the movements’ subtitles and hence emotional overtones, and spectralist composer Gerard Grisey, whose idea of the varieties of subjective ways of experiencing time in music set the agenda for the textural loading of each individual movement. Forty-Nine, Forty-Nine, for player organ tuned to a 31-step scale, keeps itself just this side of total harmonic chaos. For the title track, featuring guitarist Daniel Lippel on quarter-tone guitar, Trapani creates an intricately spatialized, electronically augmented sonic atmosphere built up of delayed and overlaid single-notes and harmonic fragments, which give the piece an undulating and beautifully unsettling, harp-like quality.

— Daniel Barbiero, 4.21.2022

Christopher Trapani is a USAmerican composer originally hailing from New Orleans. He has studied music, including a doctorate, at USAmerican universities and spent considerable time studying abroad (France) and composing and performing commissioned works in France, the UK, Germany, and Italy. His interests lie in string instruments - his website cites mandolines and microtones, folk music elements, and the concept of 'time'.

As it is not immediately audible, something that gets lost on the recordings is the mixing of instruments played live with electronic processing. Track 1 'Targul' is dedicated to the Romanian 'violin with horn', similar to the Stroh violin, able to amplify and project the violin sound. The piece plays with folk music elements, looping and repeating the live sound through speakers and a snippet of a marching band towards the end. The layering and movement of sound make for interesting listening, and you could not say whether this was composed or improvised. 'Horizontal Drift' uses a similar approach with a soloist guitar playing in quarter tones 'against' a backdrop of slowed loops. Unfortunately, this hardly kept my attention, sounding more like a noodling exercise.

What intrigued me was the centre Triptych piano piece 'Lost Time'. 3 'movements' with titles picked from Bob Dylan's songs show some wit, both in the compositions (music and length, the 'Time is a jet plane' fittingly only lasting 32 seconds) and the choice of titles. You could call the style somewhere between Impressionism and Expressionism, Debussy and Ravel. 'Linear A' (interestingly reading 'Linear A.mp3' on disk) is a wind instrument piece, as is 'Forty-Nine', and the final track 'Tesserae' returns to the violin. All of them are supported/complemented by electronics and exploring harmonics and the

essence of sound. The electronics are not recognisable as they are used to live-process the instrument sound - which, again, demonstrates some wit in handling 'sound'. Audio-wise I would say this is a release that is quite close to 'industrial' and 'electronic' approaches, thus building more of a bridge between the two (or three?) worlds than many other 'contemporary classical' releases.

— Robert Steinberger, 4.19.2022

Christopher Trapani’s latest portrait recording for New Focus features pieces for solo instruments, several with electronics. The composer’s work with microtones and hybrid tuning systems is spotlighted. Trapani has a compendious knowledge of microtonality, and he brings it to bear eloquently in the programmed pieces.

The album’s opener, Târgul, is written for vioara cu goarna, a Romanian variant on the stroh violin, a violin with an added horn to provide greater projection. It also can provide fascinating timbres, as Maximilian Haft’s performance illuminates. Dan Lippel plays the title track on quarter tone guitar, abetted by real time electronics edited by a Max patch. It is a standout piece, with sinuous passages of quarter tones and glissandos followed and morphed by electronics. The use of complex arpeggiations is riveting.

Linear A is performed by clarinetist Amy Advocat. It uses still another tuning, the Bohlen-Pierce scale, which repeats at the twelfth instead of the octave. The electronics provide clarinet duets that make the already surreal environment of the scale enhanced by buzzing overtones. Lots of florid playing, which Advocat executes with aplomb.

Lost Time Triptych is an amalgam of influences. Written as a companion piece for Gerard Grisey’s Vox Temporum, it has three detuned pitches that play a pivotal role in the music. Each of the Triptych’s movements is subtitled with a phrase from Bob Dylan. Marilyn Nonken plays the piece with detailed balancing of its intricate harmonies and supple dynamic shading. Forty-Nine, Forty-Nine is for a 31-tone equal tempered Fokker organ that is controlled by MIDI rather than an organist. With a feisty analog demeanor, it is reminiscent of some of the electronic pieces from the Columbia-Princeton Center,

The recording closes with Tessaræ, a piece written for the viola d’amore. This instrument has sympathetic strings, and Trapani deploys it to emulate folk music from Turkey and India that also has instruments with sympathetic strings. The viola d’amore’s capacities for harmonics and drones are set against a mournful mid-register melody. It is an affecting work that demonstrates Trapani’s capacity for emotional writing as well as technical innovation. Marco Fusi plays with a strongly delineated sense of the counterpoint employed in the piece.

Horizontal Drift is a compelling recording, demonstrating Trapani’s craft and imagination in equal abundance. Recommended.

— Christian Carey, 9.01.2022