Guitarist Daniel Lippel’s newest release, Adjacence, is a compilation of several chamber works recorded with various ensembles and collaborators (International Contemporary Ensemble, counter)induction, Flexible Music, Bodies Electric, and various freelance colleagues) that integrate varied aesthetics into one programmatic arc. The program highlights music across the stylistic spectrum, incorporating microtonality, improvisation, timbral experimentation, and carefully managed ensemble textures to create a broad snapshot of chamber repertoire with guitar by many of the community’s prominent composers. All but two of the works (Davidovsky and León) are heard in their premiere recordings and all but two others (Speach and Ko) were written for the ensembles heard on this recording.

Adjacence highlights music involving guitar that invests in a variety of musical parameters, including Ken Ueno’s exploration of a just intonation scordatura, Tyshawn Sorey’s deft balance between intricately through-composed material as a springboard for improvisation contrasted with Tania León’s structured open form score, Mario Davidovsky and Charles Wuorinen’s tightly argued modernism, Nico Muhly and Peter Adriaanz’s personal approaches to minimalism, Sidney Marquez Boquiren and Peter Gilbert’s programmatic expressionism, Bernadette Speach’s timbral exploration, and Tonia Ko and Carl Schimmel’s instrumentation driven invention. The album is both a compendium of several avenues in contemporary guitar chamber music as well as an expression of a conviction that underlying musical components bind together diverse aesthetics more than they separate them.

Initially conceived as a short overture to the included recording of Tyshawn Sorey’s Ode to Gust Burns, Utopian Prelude fulfills a dual role as an invitation to the album as a whole. Taking loose inspiration from selected material in Sorey’s guitar part, the short work combines through-composed material with a short improvisation.

Mario Davidovsky wrote Cantione Sine Textu in 2001 for the UC Davis based Empyrean Ensemble, wryly choosing the title itself as the text for this “wordless song.” He treats the soprano largely like one of the instruments, weaving it into his characteristically intricate ensemble mechanisms. This recording was made four days after Davidovsky passed away, his profound impact on the music world and infectious spirit very present in the hearts of everyone involved in its production.

Read MoreKen Ueno’s Ghost Flowers was commissioned by the International Contemporary Ensemble for a performance on Lincoln Center’s Out of Doors Festival in 2017. The piece grows out of an overtone based guitar scordatura Ueno developed where each open string is tuned to partials of a detuned low C string. Opening with non-pitched scratching sounds that are punctuated by percussive accents, Ueno slowly reveals the pitch language of the piece as if opening petals of a flower.

Peter Gilbert’s Neñia (Canción Fúnebre), written in 2004, sets a poem by Carlos Guido y Spano about South America’s cataclysmic War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870). Gilbert’s setting captures the wrenching history through driving irregular rhythms, poignant leaps in the soprano line, powerful dissonances, and ethereal resignation.

Nico Muhly’s Wedge was written for percussionist Jeffrey Irving and guitarist Daniel Lippel’s Irving Lippel Project in 2003. Interwoven passagework between vibraphone, marimba, and guitar is punctuated by accents that outline irregular groupings on bass drum and metals. Sections guided by long lined cantus firmi (as well as an embedded Purcell quote) are filtered through a nuanced approach to managing repeated minimalist cells.

Tonia Ko’s Moments is a collection of five miniatures for piccolo and guitar that evoke the subtleties and elegance of French music of different eras, from Poulenc to Couperin.

Peter Adriaansz' Serenades II to IV (No. 23) for three electric guitars and electric bass is a Sonic Youth inspired addition to the repertoire for layered guitars. Written for the Catch Electric Guitar Quartet, the opening serenade juxtaposes modular, repetitive cells that are colored with microtones and timbral variations, the second is an expansive chorale, and the final futuristic serenade features a soaring melodic line on ebow over a series of dense vertical harmonies with varying delay speeds and durations.

Tyshawn Sorey’s Ode to Gust Burns pays homage to the iconic Seattle based improvising pianist through its extended keyboard feature, while placing it in dialogue with the other three instruments through complex rhythmic interplay. The score includes three open sections for improvisation based on the composed material.

Carl Schimmel's The Alphabet Turn'd Posture Master, or The Comical Hotch-Potch was written for the Flexible Music quartet in 2008. It is inspired by an illustrated print from 1782 portraying a "posture master", or contortionist, forming the letters of the alphabet with his body.

Sidney Marquez Boquiren’s Five Prayers of Hope was premiered on March 7, 2020, in a concert just days before the beginning of the Covid-19 lockdown. Through the piece, Boquiren addresses distinct, pertinent issues of justice in our time, from migration to sexual violence to environmental stewardship. The music is graciously eclectic, from the timbral experimentation of the opening and closing movements, through the Messiaen influenced expansiveness of “Sanctuary,” to the fierce determination of “Silence Breakers.”

Tania León wrote Ajiaco for the Schanzer/Speach Duo in 1992. León’s open form score allows for freedom in the performance, providing a road map with several motivic fragments and encouraging the players to spontaneously decide on some aspects of their sequence. Characteristic Latin American rhythms establish an infectious groove which provided a springboard for further improvisation in this performance.

Bernadette Speach’s Échange explores extended techniques for an uncommon instrumentation of guitar, piano, and percussion. The percussion part is performed entirely inside the piano, placing the focus of the sound world of the piece within the extended keyboard timbre and its interaction with the sonic palette of the guitar.

Charles Wuorinen’s Electric Quartet, written for Bodies Electric, navigates through a mix of contrapuntal and unison passages, with two notable sections that suspend the prevailing percolating activity in favor of elastic glissandi and obscured pitch.

Dystopian Reprise is a fusion-inspired improvisation using the final minutes of Peter Adriaansz’ Serenade IV as a canvas.

– Daniel Lippel

Executive producer: Daniel Lippel

Session producers: Ryan Streber, all tracks except: Ryan Streber and John Link (Davidovsky), Bernadette Speach (Speach), David Crowell and Daniel Lippel (Adriaansz III and IV, Adriaansz/Lippel, Lippel), Flexible Music (Schimmel), Peter Gilbert (Gilbert), Sidney Boquiren and Ryan Streber (Boquiren)

Recording engineer: Ryan Streber, all tracks except: David Crowell (Adriaansz III and IV, Lippel, Adriaansz/Lippel), Scott Fraser (viola on Ueno), Christopher Jacobs (Schimmel)

Editing: Ryan Streber, all tracks except: David Crowell (Adriaansz III and IV, Adriaansz/Lippel, Lippel), Peter Gilbert (Gilbert), Daniel Lippel (guitar on Ueno)

Editing producer: Daniel Lippel, all tracks except: Peter Gilbert (Gilbert), Ryan Streber and Daniel Lippel (Muhly, Sorey), David Crowell and Daniel Lippel (Adriaansz III and IV, Adriaansz/Lippel, Lippel)

Mixing engineer: Ryan Streber, except David Crowell (Adriaansz Serenades and Dystopian Reprise)

Mastering engineer: Ryan Streber (Oktaven Audio, Mt. Vernon, NY)

Artwork, Design and Layout: Kate Gentile

This recording has been funded in part by support from the Aaron Copland Fund for Music Recording Program, University of California at Berkeley Music Department (Ueno), the International Contemporary Ensemble (Sorey), University of New Mexico Music Department (Gilbert), and the Roger Shapiro Fund (Wuorinen). Many thanks to Pete Harden, Bernadette Speach, Neil Beckmann, and Jeffrey Irving for assistance with obtaining and collating scores and clarifying performance details; Ken Ueno, William Anderson, Peter Gilbert, Karola Obermueller, Ross Karre, Peter Adriaansz, Bernadette Speach, and Jeff Irving for facilitating funding support; Jessica Slaven, Eric Huebner, and Scott Fraser for help coordinating recording logistics; Haruka Fujii, John Chang, the International Contemporary Ensemble, and counter)induction for creating the circumstances that allowed for the creation of some of these works; Marc Wolf and Neil Beckmann for behind the scenes label collaboration; Kate Gentile for bringing so much to the design; David Crowell for artful and enthusiastic work on sessions which didn’t have a template; Ryan Streber for ever inspiring virtuosity and musicianship behind the controls; and of course to the composers and performers, thank you so much for lending your inspiring artistry to this project and sharing it with all of us.

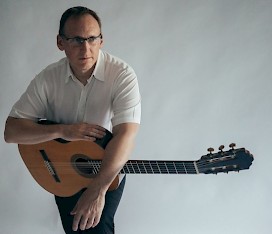

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

Adjacence is the new album from guitar virtuoso Dan Lippel, playing solo as well as in the company of individual players and chamber groups of various sizes. The selection here is very rich: fourteen compositions by thirteen recent and contemporary composers, including two composed or co-composed by Lippel.

The stylistic diversity of the album’s music clearly demonstrates Lippel’s versatility as a performer. For example, there is Ken Ueno’s Ghost Flowers, a mostly sound-based work of scraped strings and plucked notes in just intonation, for guitar, viola (Wendy Richman), and dulcimer (Nathan Davis); Moments, the elegant five-movement duet for acoustic guitar and piccolo (Roberta Michel) by composer Tonia Ko; Tyshawn Sorey’s darkly atmospheric Ode to Gust Burns for small ensemble, which combines composed and improvised passages; Carl Schimmel’s The Alphabet Turn’d Poster Master for electric guitar, tenor saxophone (Timothy Ruedeman), piano (Eric Huebner), and percussion (Haruka Fujii), a work of fragmentary motifs and intricate unison lines; the dissonant minimalism of Peter Adriaansz’s Serenades II-IV, with Lippel overdubbed on electric guitars and electric bass; and Tania León’s dramatic Ajiaco for piano played inside and out (Cory Smythe) and Lippel’s reverb-soaked electric guitar, spinning out deconstructed jazz-like lines.

Among the album’s many highlights is Charles Wuorinen’s Electric Quartet (2013) for four electric guitars. The piece was commissioned by the guitar quartet Bodies Electric, of which Lippel is a member; the performance here is theirs. The piece contains a complex skein of lines, as one would expect from Wuorinen; Bodies Electric’s realization is a model of polyphonic clarity. Another is Nico Muhly’s propulsive Wedge, which features Lippel on classical guitar and Jeffrey Irving on vibes and other percussion playing additive and subtractive variations on short motifs over shifting time signatures.

In a bit of structural symmetry Lippel’s Utopian Prelude, which features the composer on electric guitar and microtonal classical guitar and Ryan Streber on electronics opens the album; Dystopian Reprise for Lippel on solo guitar, co-composed by Lippel and Adriaansz, closes it.

Adjacence is a fine survey of what the guitar is capable of at this moment in musical time.

— Daniel Barbiero, 11.09.2024

Also out yesterday, this sprawling, adventurous, *essential* collection of new chamber works for guitar. Featuring 14 pieces and 12 premiere recordings, this will become a bible for new music guitarists!

— Jeremy Shatan, 11.16.2024

American guitarist Daniel Lippel has premiered more than fifty new solo and chamber music works, many of which were written for him. He has recorded several of these on the independent label New Focus Recordings, which he co-founded and runs.

With this album, he offers good insights into the contemporary guitar repertoire, including works for solo guitar, acoustic guitar and tape and electric guitar as well as chamber music.

The energetic and minimalist Wedge by Nico Muhly, the original and interestingly composed Moments by Tonia Ko and the sonically exciting Serenades by Peter Adriaansz with its electronic treatment stand out from the first part.

In the second part, the atmospheric Five Prayers of Hope by Sidney Marquez Boquiren, which is so different in its moods, deserves attention. Sophisticated interpretations and good sound recordings are further plus points of the double album.

— Norbert Tischer, 11.22.2024

Adjacence is the recent release from New Focus Recordings of solo and chamber compositions featuring guitar from a variety of contemporary classical composers. The one hundred and twenty-eight minute double album is available in both CD and digital format, and it includes a booklet with liner notes by Daniel Lippel, a guitarist on all the pieces showcased in the album. In addition to Lippel, the album features an extensive group of performers, specifically guitarist Oren Fader, guitarist John Chang, guitarist William Anderson, soprano Nina Berman, soprano Elizabeth Weigle, bassist Randall Zigler, clarinetist Amy Advocat, flautist Roberta Michel, dulcimerist Nathan Davis, violist Wendy Richman, violist Jessica Meyer, percussionist Jeffrey Irving, percussionist Haruka Fujii, percussionist Clara Warnaar, pianist Eric Huebner, pianist Karl Larson, pianist Cory Smythe, pianist Renate Rohlfing, saxophonist Timothy Ruedeman, violinist Nurit Pacht and bassoonist Rebekah Heller.

This double album highlights works by composers from across the landscape of 'contemporary artists', to use Lippel's terminology, though it appears to focus specifically on the established academy-supported subgenre of contemporary classical music in the United States that often identifies itself as 'New Music', based on the composers and sonic profiles included. (Lippel himself does not use this identification here.) This idiom is, one might say, characterized by a kind of maximalism in miniature. There has evolved within academy-adjacent circles a compositional vernacular which intentionally and regularly brings to the fore the full range of modern and contemporary sonic innovations in Western art music, compressed in scale for the purposes of cohesive presentation and study in an intimate studio setting by would-be contemporary composers. It is this New Music vernacular which is audibly present throughout this album. Within this audible context, Lippel articulates the goal of this guitar project as 'a chronicle of an attempt to make music not in opposition to any one credo or in uncritical embrace of another, but on an adjacent path', the implication being that the art form in question otherwise trends toward ideological motivations which remain unnamed in the booklet essay. In any case, such ideological associations are what this project seemingly aims to transcend by reframing these pieces of music through a novel perspective of pure sonic focus. To this end, Lippel has assembled an astonishing diversity of creative voices contributing to the guitar repertoire in the New Music context.

The album opens with Daniel Lippel's Utopian Prelude for electric and microtonal classical guitar, a freely atonal piece juxtaposing polyphonic and homophonic textures.

This is followed by Cantione Sine Textu (meaning 'song without text') for soprano, clarinet, bass clarinet, flute, piccolo, alto flute, bass and guitar, composed by Mario Davidovsky on the text of the piece's title itself. Another freely atonal work, the piece continuously alternates between dense and sparse ensemble textures.

Next is Ghost Flowers for violin, dulcimer and guitar, composed by Ken Ueno. This composition showcases a fast landscape of scraping glissando gestures punctuated by accented plucked single notes. Gradually the plucked notes themselves emerge as the dominant landscape material before further developing into masses of melodic imitation. The following piece is Peter Gilbert's Neñia (Canción Fúnebre) for guitar and soprano, a lyrical and comparatively diatonic setting of a poem by Carlos Guido y Spano which recounts the War of the Triple Alliance in South America. This is followed by Nico Muhly's Wedge for percussion and guitar, a quasi-minimalistic pandiatonic piece for guitar and percussion in which a looped motif gradually transforms its melodic and metrical content in various registers.

Next is Moments for piccolo and guitar, a piece in five movements composed by Tonia Ko.

Movement one, 'Momentum', is fast-moving and freely atonal, while the next movement, 'Légèreté (on two cadences by Couperin)', is slow, quiet and hesitant. Movement three, 'Interlude', is slower and quieter, while movement four, 'Crossing Paths', proceeds with a medium tempo and an imitative texture. The fifth and final movement, 'Memento', has a slightly louder dynamic at medium tempo with the piccolo leading the guitar.

The first disk closes with Serenades II to IV (No 23) for electric guitars and electric bass, composed by Peter Adriaansz. 'Serenade II', the first of these three, is a medium-tempo minimalist movement made up of alternating blocks of sound. Here the frequency of transitions between the blocks of sound itself becomes a centrally expressive composition parameter. 'Serenade III' is a slower movement with a similar conceptual structure to the previous one using dense pandiatonic harmonies. The last of the three movements, 'Serenade IV', has a medium tempo and a two-against-three polyrhythm.

Disk two opens with Ode to Gust Burns for bassoon, percussion, piano and electric guitar, composed by Tyshawn Sorey. Here, masses of sound glacially unfold with varying internal organization of textural, timbral and dynamic material. This is followed by The Alphabet Turn'd Posture Master, or The Comical Hotch Potch for percussion, piano, tenor saxophone and electric guitar, composed by Carl Schimmel. Here we hear rapid alternation among numerous ensemble textures, such as monophony, polyphony and homophony.

Next is Five Prayers of Hope for violin, viola, piano and guitar, a piece in five movements composed by Sidney Marquez Boquiren. The first movement, 'Beacon', is characterized by an undulating landscape of tremolo and glissando. Movement two, 'Bridges', showcases a lyrical layering of notes emphasizing diatonic subsets within freely atonal pitch collections. The third movement, 'Silence Breakers', is fast-paced, showing imitative polyphonic interplay between instruments. Movement four, 'Sanctuary', is a comparatively long and slow-pulsing movement with an aria-like melodic line.

The piece ends with the fifth movement, 'Home', in which a single vibrant sound mass emerges and then subsides.

Ajiaco follows, a piece for piano and electric guitar composed by Tania León. Here, we hear an undulating sound mass with an imitative polyphonic internal structure. Next is Échange for piano, percussion and guitar, composed by Bernadette Speach. This is a medium-slow piece in which various textural and rhythmic organizational methods morph into one another, including free rhythms, polyrhythms and pointillism. This is followed by Electric Quartet for four electric guitars, composed by Charles Wuorinen, a medium-tempo piece with an imitative and freely evolving textural structure. The album closes with Dystopian Reprise for solo electric guitar, an improvisation by Daniel Lippel on one of the previously heard Adriaansz Serenades. Here we hear Lippel's improvisation unfolding over multiple layers of sustained chords.

In an era when much music created by - and for - academy-adjacent circles is done so in service to ideological debates through aesthetic avatars, a release like this stands out for its openness of pure sonic expression. It is, in effect, a collection whose message celebrates the toolbox of the musical rhetorician without the teleological constraints of rhetoricism itself. While the individual pieces featured on this album have diverse origins with original circumstances necessitating different purposes, Lippel's curation and presentation of the collection has the effect of transcending these circumstances. In this way, the album highlights their shared flexible and virtuosic vernacular of New Music using the guitar as a focal point. For this reason I consider this release a valuable and necessary addition to the recorded discography of compilation albums in the medium.

— John Dante Prevedini, 1.22.2025

Elsewhere in these pages you will find reviews of guitar-centric discs featuring “classical” composers Graham Flett and Tim Brady, and jazz guitarists Jocelyn Gould and the late Emily Remler. Each of those discs showcases, primarily, one style of music, albeit there is quite a range in each of the presentations. The next disc also focuses on guitar, but in this case it appears in many forms and contexts.

ADJACENCE – new chamber works for guitar (new focus recordings FCR 423 danlippel-guitar.bandcamp.com/album/adjacence) features the talents of Dan Lippel on traditional and microtonal classical guitars, electric guitar and electric bass in a variety of ensembles and settings. The 2CD set features the work of a dozen living composers and includes pieces by the late Mario Davidovsky (Cantione Sine Textu for wordless soprano, clarinet/bass clarinet, flutes, guitar and bass) and Charles Wuorinen (Electric Quartet performed by Bodies Electric in which Lippel is joined by electric guitarists Oren Fader, John Chang and William Anderson). There are works for solo guitar, multi-tracked guitars, an unusual string trio comprised of guitar, viola and hammer dulcimer, a variety of duets such as piccolo and guitar and percussion and guitar, and a number of quartets of varied instrumentation.

One of my favourites is Tyshawn Sorey's homage to a Seattle-based pianist/composer. Titled Ode to Gust Burns it is an extended work scored for bassoon, guitar, piano and percussion, with the bassoon adding a particularly expressive note to the tribute. Another is Lippel’s own Utopian Prelude that opens the set, on which he plays both electric guitar and a micro-tonally tuned acoustic instrument. Ken Ueno’s Ghost Flowers is another extended work, composed for the unusual trio mentioned above. It begins with eerie string rubbing sounds from the guitar before droning viola and percussive dulcimer join the mix.

The next ten minutes get busier and busier with overlapping textures and rhythms before subsiding gradually into gentle harmonics. Peter Adriaansz’s Serenades II to IV (No.23) for electric guitar and electric bass ends the first disc, with Lippel playing both parts. Sidney Marquez Boquiren’s Five Prayers of Hope is performed by counter)induction, a quartet consisting of violin, viola, guitar and piano. The haunting opening prayer "Beacon" is juxtaposed with a variety of moods in the subsequent "Bridges," "Silence Breakers," "Sanctuary" and "Home." The second disc ends with Dystopian Reprise which Lippel describes as “a fusion-inspired improvisation using the final minutes of Adriaansz’s "Serenade IV" as a canvas.” Throughout the more than two hours of Adjacence Lippel and his colleagues kept me enthralled with the breadth and range of an instrument it is all too easy to take for granted.

— David Olds, 2.08.2025

The breadth of America’s contemporary music scene is captured in Adjacence, the latest release from Brooklyn-based guitarist Daniel Lippel. The double album brings together an eclectic group of 14 chamber works for ensembles large and small, ranging from music by established composers like Charles Wuorinen, Tania Léon, and Nico Muhly to pieces by important newer voices. As a soloist with groups like International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) and as co-founder of the indefatigable New Focus Recordings, Lippel has probably done more to introduce audiences to the diversity of modern guitar repertoire than anyone else in his generation.

There are too many works here to comment on each individually, but suffice it to say there are no duds and a range of textures to suit every ear. At one end of the spectrum sits Lippel’s haunting Utopian Prelude, combining the sounds of microtonally fretted classical guitar with electric guitar. Ditto Ken Ueno’s intricate Ghost Flowers, which uses a guitar scordatura technique to create a unique sound world of plucked and agitated strings.

At the other are works like Muhly’s feel-good, percussion-enhanced Wedge; Tonio Ko’s elegant, baroque-flavored Moments (for the unusual combination of guitar and piccolo); or Carl Schimmel’s cartoonish The Alphabet Turn’d Posture Master, or The Comical Hotch-Potch for saxophone, guitar, piano, and percussion. My personal favorite: Peter Adriaansz’s Sonic Youth-inspired Serenades II to IV for three electric guitars and electric bass, all performed by Lippel in a hypnotic soundscape destabilized by tonal shifts, reverb, and delays.

— Clive Paget, 3.04.2025

Guitarist Daniel Lippel has put together a program of contemporary chamber music centered on his instrument that celebrates the unprecedented aesthetic and stylistic diversity of our time. As he puts it in his program notes, his intention is to embrace an “either and” approach rather than an “either or” one. He opens the large collection with his own music, a solo work written for a microtonally fretted guitar. That unusual feature, as well as the eerie nature of the music, suggests the influence of Harry Partch. The late Mario Davidovsky is represented by a delicately constructed chamber work for guitar, clarinet, double bass, flute, and a wordless soprano (thus the title, Cantione sine textu). The playfulness and careful construction is typical of this master, who died just days before this recording was made. With Ghost Flowers by American composer Ken Ueno, Lippel returns to a prepared guitar in work that gradually increases in intensity during the course of 13 minutes, featuring a unique texture created by a harsh guitar timbre combined with viola and dulcimer.

Peter Gilbert’s Neñia is a setting of a poem by Carlos Guido y Spano for soprano and guitar about a bloody war in 19th-century South America. The music balances folkloric elements in both the singing and the guitar accompaniment, which is peppered with dissonance that seems to reflect the horrific nature of the poem. Nico Muhly is one of the most admired composers of his generation, known for his flowing melodic work and strong emotional content. Wedge is an earlier work (2003) written in his student days, and has more of a Minimalist quality than his current work, perhaps as a result of his stint as an assistant to Philip Glass beginning around this time. Tonio Ko’s music might also be considered Minimalist, but in an entirely different way. Her five Moments for piccolo and guitar are short and spare, and although she ascribes French music as her muse in this work, a certain Asian quality of concision and sheer beauty is also present. Disc 1 concludes with an otherworldly set of serenades for three electric guitars and electric bass by Peter Adriaansz, all played by Lippel via the magic of over-dubbing. There is melodic and rhythmic interest in these works, and a beguiling use of microtonality, but it is above all the rich, exotic sonority of this combination of electronic instruments that makes this music so compelling.

Tyshawn Sorey is one of the most fascinating musicians on today’s New Music scene. He is probably best known as a jazz drummer (I was recently dazzled by his playing at a concert with Prism Quartet, the superb saxophone foursome), but he is also a daring and deeply thoughtful composer, as heard in this 2012 tribute to a kindred spirit, the experimental jazz pianist and composer Gust Burns. Sorey’s music, at least what I have heard to date, is distinguished by rich sonorities and careful timbre blending, lending his sound a contemporary Gallic signature. Ode to Gust Burns is scored for electric guitar, piano, bassoon, and percussion. The title of Carl Schimmel’s 2008 work for electric guitar, piano, tenor sax, and percussion, The Alphabet Turn’d Posture Master, or The Comical Hotch Potch, seems to promise qualities of humor and adventure, and that is what we get. The work was inspired by an 18th-century print depicting a contortionist, which is aptly reflected in the rollicking, intensely rhythmic score.

The mood of Sidney Marquez Boquiren’s Five Prayers of Hope returns the program to a somber spirit, with reflections of the contemporary aura c. 2020 (just before the pandemic lockdown), with music for guitar, piano, violin, and viola. The five sections are entitled “Beacon,” “Bridges,” “Silence Breakers,” “Sanctuary,” and “Home,” with each one honoring the emotional sense of these words. The concluding piece, “Home,” offers the sense of hope and determined optimism that is harder to draw from the often bleak preceding music. Tania León’s 1992 work for electric guitar and piano takes its name, Ajiaco, from a Latin American soup or stew. León’s musical palette is very eclectic, and includes music with a folkloric inspiration, drawn from her Cuban heritage, but she also writes much harmonically inventive works of a more intellectual nature. Ajiaco falls into the latter category, although it is anything but dry; on the contrary, it is quite tasty. The rich textures and fascinating twists and turns whetted my appetite, and inspired me to look up a recipe for Ajiaco. Bernadette Speach’s Échange, from 1982, is the oldest work here, and the only one from the 20th century. The music is odd, but in a good way, exhibiting an unshowy quirkiness that conveys a stealthy sense of joy. A very unusual aspect of the piece for piano, percussion, and guitar is that the piano is shared by both the keyboardist and the percussionist, whose work takes place exclusively under the instrument’s lid. The late Charles Wuorinen, that serialist stalwart, is represented by a typically complex yet paradoxically lyrical composition for four electric guitars. Lippel’s impressive omnibus concludes with his jazzy riff on the closing section of last serenade of Peter Adriaansz heard previously.

In all, this is a feisty, eclectic review of the current state of New Music for guitar, most certainly leaning in an avant-garde direction. Daniel Lippel’s ambitions are lofty, but he pulls it off in with a program that is full of surprises, a gamut of emotions, innovation, and not a little bit of grunge.

— Peter Burwasser, 4.03.2025

The Romantic tradition of the Spanish guitar and the raucous rock world of the electric guitar provide sounds our ears are familiar with almost by second nature. In their pure form the two instruments have entered classical music in a limited way. Performers can be grateful, then, to New Music composers like the 13 represented in this striking and varied collection, for re-imaging much wider uses—one might even say new personalities—for the acoustic and electric guitar. All but two pieces are world premiere recordings. The span of dates is more than a generation, from 1982 to 2020. Guitar fanciers should proceed eagerly, especially those with a taste for contemporary music.

General listeners might wind up picking and choosing, guided by samples from online listening sites after reading this review—that’s my practice with unfamiliar music. At the center of this project is Dan Lippel, the proprietor of the artist-driven label, New Focus, who is also a guitar virtuoso. As Lippel comments in his program notes, which provide succinct, cogent descriptions of the 13 pieces on the program, this two-CD set offers a snapshot of diverse styles (i.e., all over the map), giving the listener a vivid representation of how the guitar figures in contemporary chamber music. All but two pieces are performed by the artists who commissioned them.

I’m averse to laundry-list reviews, believing that readers will get more out of some impressions and highlights. My first impression was surprise at pieces where the guitar appears in tonal or tonally-inclined works; I expected tougher harmonies. My expectation of sending up pink flags was unwarranted. There’s almost pure entertainment in Wedge, a duo for guitar and percussion by Nico Muhly, beginning with his synthesis of moto perpetuo and Minimalism that offers scope for Lippel to demonstrate his bravura technique. The same is true of percussionist Jeffrey Irving, who manages a flurry of brilliant passagework on vibraphone, marimba, metals, and drum. Wedge could hardly be rivaled for cleverness.

Just as accessible is Moments, a suite for piccolo and guitar by Tonia Ko. Its five miniature movements aim to evoke the subtleties of French music from Couperin to Poulenc. I couldn’t detect that, but the suite as a whole seems French in being a light-as-air divertissement. Imagination and easy assimilation are combined in The Alphabet Turn’d Posture Master, or The Comical Hotch Potch, a mixed quartet (piano, percussion, saxophone, electric guitar) by Carl Schimmel. New Music has a hard time expressing well-defined emotions, but Schimmel’s piece is cleverly funny. He was inspired by an 18th-century print of a contortionist twisting his body into the letters of the alphabet (the “posture master” in the title). This led to a musical hodge-podge of antic, at times zany, musical ideas that romp before our eyes and exit before they have worn out their welcome.

Sidney Boquiren’s Five Prayers of Hope, which premiered just before the pandemic lockdown, is also a mixed quartet for violin, viola, piano, and guitar, the lineup of acoustic instruments providing a warm, familiar sonority. There are some restless, agitated parts, but on the whole the soulful, melody-driven music serves the welcome purpose of genuine consolation.

Lippel plays in all 13 works, so it’s reasonable to highlight the pieces where he is most prominent, in solos and duos. The first of these, composed by Lippel himself, is Utopian Prelude for microtonal guitar and electric guitar. The piece is atonal and abstract, but it continues the free-form tradition of the prelude, which originated with Renaissance lutenists. The piece also introduces us to the two broadly defined functions of the guitar on this album, either playing through-composed music or improvising. Utopian Prelude illustrates both; the improvised part is quietly meditative for a time. The program closes in the opposite mood with Dystopian Reprise, an unsettling improvisation from Lippel on material from another piece here, Peter Adriaansz’s Serenade IV. I’d call it a kind of atonal hard-rock blast for electric guitar that is played with suitable abandon for its dark mood.

The three disarmingly titled Serenades II to IV by Adriaansz exemplify music that doesn’t simply come at you; it comes for you. Aggressive drive and manic motor rhythms propel the two outer Serenades, while the middle one’s long sustained tones are a respite, perhaps a recovery period. It must have been a fantastic workout for Lippel to coordinate himself on layered electric guitars and bass as an overlapping ensemble. Somewhat opaquely, Tania León titled her duo for electric guitar and piano Ajiaco, after an earthy meat-and-potatoes stew popular in South America. The score is in open form, with indications of certain gestures while leaving large scope for improvisation. Latin American rhythms are embedded in some thematic fragments. I must admit that I wasn’t able to tell the difference between this atmospheric, evocative performance and a through-composed one.

The risk of a laundry list is looming, and I regret that I can’t detail the specialized techniques and sound worlds expressed in the remaining works. Radical gestures like the untuned strings at the basis of the scordatura tuning in Ken Ueno’s Ghost Flowers will strike some listeners as novel experimentation and others as abrasively alienating. Very little is so esoteric, however, that it requires a coterie audience to decipher it. I was totally bored by only one work, Charles Wuorinen’s uninspired Electric Quartet. The rest are genuinely imaginative works that repay the time and attention they ask for, and I don’t doubt that a sympathetic ear will find many sources of enjoyment. Dan Lippel is too young for this to be a legacy album, so let’s call it a legacy for the time being.

— Huntley Dent, 4.03.2025

Guitarist Daniel Lippel’s newest release is a diverse collection of solo and chamber works for both traditional acoustic and electric instruments on two CDs. These works span a period of nearly 40 years, all of them written during the guitarist’s lifetime. The oldest dates from 1982 and the most recent from 2024, and they vary greatly in compositional quality and musicality. More on that anon.

There are two common denominators to this collection, irrespective of one’s views of particular composers or particular compositions therein. The first is the manifestly high level of musicianship and technical proficiency among the 21 different performers with whom Lippel has collaborated to make this collection. The other is Lippel himself, whose virtuosity on acoustic and electric guitars is displayed throughout. His collaborators are, as the headnote reveals, a diverse array of extremely talented musicians; their performances highlight a number of different compositional styles (and, in some cases, fads), all within a musical aesthetic that emphasizes textures and sonic envelopes, sometimes for their own sake and sometimes in aid of a larger compositional vision.

This recent compilation of chamber works, recorded with various ensembles and collaborators—International Contemporary Ensemble, counter)induction, Flexible Music, Bodies Electric, and various freelance colleagues—bookended by solo guitar riffs on two of the compositions, integrates varied aesthetics into one programmatic arc. The program highlights music across the stylistic spectrum, incorporating microtonality, improvisation, timbral experimentation, and carefully managed ensemble textures to create a broad snapshot of chamber repertoire with guitar. All but two of the works (Davidovsky and León) are heard in their premiere recordings, and all but two of the others (Speach and Ko) were written especially for the ensembles heard on this recording.

A bit like a walk down memory lane are works by veteran composers of the postwar serial and early electronic music period. Mario Davidovsky and Charles Wuorinen were friends and contemporaries of one of my own mentors, Milton Babbitt, and, in the case of Davidovsky, collaborated in the creation of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center (back in the day when mainframe computers took up entire buildings), even though both of their works on this disc were composed much later: Davidovsky’s Cantione sine textu (which was recorded a scant four days after the composer’s death) dates from 2001 and Wuorinen’s Electric Quartet from 2013. Even those who do not appreciate that aesthetic will be able to discern that these are serious, well-conceived musical compositions. I also very much enjoyed:

(1) Échange (the oldest composition on the program), which was composed for guitar, piano, and percussion by Bernadette Speach (who was a student of Morton Feldman) back when she was starting to make a name for herself;

(2) Ajiaco, for electric guitar and piano, which was originally commissioned by the Schanzer/Speech duo from Tania León (who recently began a stint at composer in residence for the London Philharmonic);

(3) Tyshawn Sorey’s quirky but rhythmically interesting Ode to Gust Burns; and

(4) Tonia Ko’s elegant Moments, for piccolo and guitar.

A particular delight, bursting with humor, is Carl Schimmel’s The Alphabet Turn’d Posture Master, or The Comical Hotch-Potch, which was written for the Flexible Music quartet in 2008; this is the piece on these discs that I fancy I shall return to most often.

The other compositions were far less interesting musically, for particular reasons or combinations of reasons. Music can be noisy, but noise and music are not synonyms. Some of the pieces I dislike are those that seem gimmicky for the sake of being gimmicky; others are rather tedious examples of Minimalism. I confess my prejudices against works that are more noise than music and works that are repetitious, non-developmental, lacking in any semblance of musical complexity (or all of the foregoing) wrapped in one boring package. These may be some listeners’ cup of tea, but they are not mine.

Those listeners who are steeped in avant-garde classical music (a self-selecting group, perhaps) and those others who are adventurous may be attracted to this potpourri of seldom heard but well-performed solo and chamber works. Recommended especially for the compositions identified above.

— Keith R. Fischer

New Focus Recordings is an independent label devoted to contemporary music. From modest beginnings its catalog has grown to include almost 500 CDs, with more than 200 reviewed in Fanfare (visit the “Labels” section of the Archive to learn more). Cofounded by guitarist Daniel Lippel, composer Peter Gilbert, and composer/engineer Ryan Streber in 2004, the company steadfastly adheres to the premise that while “live performance will always be the most vital way to experience music … recordings offer an intimacy and a breadth of dissemination that is unique and essential.” One of the latest products of that philosophy, Lippel’s two-disc set Adjacence, brings adventurous listeners a selection of new chamber works for guitar performed with several of his ensemble colleagues, and curated to reflect a broad section of aesthetics in today’s contemporary music community.

Before getting to New Focus Recordings and Adjacence, tell us something about yourself.

I was born in Brooklyn in New York in 1976 and grew up in Montclair, New Jersey. I was lucky to have a pretty conventional suburban childhood, and went to school at Oberlin College Conservatory first, then the Cleveland Institute of Music to complete my bachelor’s and master’s degrees. I stayed in Cleveland for a few years, doing some adjunct teaching and playing freelance gigs, and then I went to the Manhattan School of Music for my doctoral degree. I’ve been in New York City since, performing in various contexts and getting more involved with recordings over time.

Are you from a musical family?

No, none of my immediate family members are musicians, but we had a decent amount of music playing at home when I was a kid. My mother played some piano when I was young and my father played a lot of recordings, first on vinyl and later on CD. On top of that, being close to New York City, I was lucky to attend concerts with my family, particularly at Lincoln Center, and Montclair also hosted some really fine performances locally, including a regular Orpheus Chamber Orchestra series at the local high school and a great jazz club called Trumpets that booked amazing musicians. By the time I was in my early teens, music had become something very central to my life.

Was guitar your first instrument?

I started with piano lessons briefly when I was a little kid. I didn’t get very far before I gave it up, and then later I played trumpet and euphonium briefly in middle school. I began playing guitar at age 11 and was pretty hooked right away. While I got more into the guitar, I also played French horn, double bass, and timpani in high school orchestra, sort of filling in where the teacher needed me as a utility player, though I never really became that proficient at any of them.

What was it about the guitar that got you hooked?

At first I was attracted to guitar for the same reason that a lot of American kids were drawn to it: I heard some rock bands on the radio and was transfixed by the electric guitar sound. This was during a heyday for hard rock on the radio, and that led me to discover some of the iconic classic rock bands in the process. But when I began lessons, it was initially on an acoustic nylon-string instrument, and I remember just being hypnotized by the resonance of the sound.

Were you immediately interested in classical music, or was it popular music that fueled your passion?

I had different interests developing concurrently. I was in a band with my friends, and we played a lot of classic rock and prog rock, covering Led Zeppelin, Rush, and similar bands, and writing some of our own songs. But I had early teachers at a local music studio called Music Magic who were really great and gave me some simple Bach arrangements, as well as introducing me to jazz guitarists like Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell, and I began to get really excited about both classical music and jazz soon after starting.

With whom were you studying before you went to Oberlin?

I began studying with Dr. Nicholas Goluses (currently the Guitar Department chairman at the Eastman School of Music) when I was a freshman in high school at age 14. I had been taking the guitar seriously before that, at least in my own mind, but I would mark meeting Dr. Goluses as the moment that I began more serious studies in earnest, and he offered me very inspiring, nurturing, and timely guidance.

Another of your teachers was David Starobin, well known to Fanfare as a guitarist and founder of Bridge Records. What led you to him?

As I was finishing my master’s degree in Cleveland, I discovered the breadth of David Starobin’s contributions to the music world as a guitarist and record producer. Prior to that I knew of him through the guitar world of course, but as I became more interested in contemporary music and was researching repertoire for the guitar, I came across many of his incredible recordings and works he had commissioned from several of the most important composers of our time. I was inspired by how he had made his career and had such a profound impact in the larger music world. At the time, I was co-directing a small contemporary chamber music series in Cleveland, and that experience had made me feel that a career which allowed me to be part of the larger musical community, playing chamber music with other instrumentalists, working with composers, etc., seemed to be a good fit for me. So I decided to apply to study for my doctoral degree at the Manhattan School of Music with David, and it turned out to be a formative period in my life. I’m very grateful to David and all of my mentors from MSM for encouraging me in my direction. Not only did David work with me on some of the pillars of the repertoire that he had commissioned, he also facilitated some of my most important collaborations that continue to this day, including introducing me to some of Nils Vigeland’s guitar music that previously had not been played. While I was finishing my dissertation, I worked at David and Becky Starobin’s label, Bridge Records, for a little over a year. I learned a lot from that experience, seeing how active they were in releasing important recordings and collaborating with so many influential musicians, and the dedication they brought to that work.

What was the subject of your doctoral thesis?

I wrote my DMA dissertation on the guitar music of Mario Davidovsky, specifically focusing on two pieces, his Synchronisms #10 for Guitar and Electronics and Festino for guitar, viola, cello, and bass, both of which he had written for David Starobin. My focus was on contextualizing Davidovsky’s guitar works within his oeuvre in general and seeing those pieces in light of his overall aesthetic interests as a composer. I was extremely lucky to have the chance to spend time with Mario, playing and getting coached by him on those pieces and interviewing him about his music. He had a very profound impact on how I understand music.

Are there other influential teachers or musicians you’d care to mention?

I have been exceedingly lucky to work with several really inspiring guitar teachers, as well as non-guitarist mentors. Aside from Nicholas Goluses and David Starobin, I met David Leisner as a student at the Bowdoin Chamber Music Festival in 1992, and continued to study with him until I finished high school and at the festival for summers after that. Leisner introduced me to the world of contemporary chamber music at Bowdoin and gave me great opportunities to work with other instrumentalists, as well as pushing me to refine my interpretive sensibilities and to think about tension in the body while I was playing. At Oberlin, I studied with Stephen Aron, who gave all of us in the guitar studio a real gift by encouraging us to focus on making a contribution to a specific area of the guitar repertoire as we developed our careers. I also took really beneficial secondary jazz guitar lessons with Bob Ferrazza while I was there.

When I studied at the Cleveland Institute of Music, I first worked with John Holmquist, who helped me to develop a more mindful approach to playing and shaped my understanding of larger formal structures. John left CIM as I was continuing into my master’s degree, and I got the opportunity to study with Jason Vieaux as he started his career teaching there. Jason gave me absolutely invaluable instruction on technique, effective practicing, and musical refinement. At the Manhattan School of Music, both Dr. Nils Vigeland and Dr. Reiko Füting were truly inspiring theory professors who gave me a totally new perspective on the many ways music can be constructed and understood, and I’ve been really lucky since then to collaborate with both of them on new pieces involving guitar and on recording projects. Of course, there are countless other musicians and mentors from whom I have learned an enormous amount, but in the interests of brevity I will leave it at the people who had the biggest impact on me during my years as a student.

Although you’re primarily a guitarist and record producer, Utopian Prelude, the first track on Adjacence, is a piece you wrote. When did you become interested in composition?

I wrote some original music in my first few years of playing guitar, but I still don’t really consider myself a Composer with a capital C. I’ve written some pieces, mostly for myself to play either solo or in ensembles, for classical guitar as well as electric, but I have never fulfilled a commission to send to other players to perform, and I’ve written very little that doesn’t involve guitar. Of the music I have written, some of the pieces are through-composed and fully notated, while some others are more in the vein of jazz tunes, with written material and sections for improvisation, sometimes in a conventional head-solos structure, and other times organized differently.

I can only speak for myself, but I see an important distinction between performers, who primarily write music for themselves to play, versus composers, whose primary writing activity is for other performers, especially on instruments that are not necessarily their own. Sometimes I prefer to call myself an “arranger of original material” as opposed to a “composer.” I may do more composing for other instruments and not include myself as a performer in the future, but up until now and currently, I’m primarily writing music for myself to play.

What were your first efforts like? Were you writing any electronic music?

It wasn’t until I had been in conservatory and studied some contemporary repertoire that anything I wrote reflected what we think of as new classical music; prior to that I wrote jazz tunes and rock songs. The only forays into composing electronic music I have really made involve using electric guitar pedals and limited layering of tracks. I’ve written some pieces making extensive use of the loop pedal (striving to subvert the typical additive looping default) and other timbral effects, and a couple of pieces that involve a pre-recorded track of my own playing that may or may not be subjected to limited processing. But I have yet to delve into any more involved electro-acoustic or electronic composition using some of the common software or processing platforms.

How has your style evolved over the years?

As a player, I would say that my style has been shaped deeply by my work with recording. The opportunity to really sculpt one’s interpretation, in preparation of a session, during a session, and in the editing process has really changed the way I hear music in general, especially as it pertains to detail and expressive subtlety, and that has influenced the way I play in live settings as well, despite the two contexts demanding a different orientation in the moment. Additionally, all the different kinds of repertoire I’ve encountered invariably have impacted me in ways I may not have initially expected. Studying and performing music with extended techniques like Lachenmann’s famous guitar duo Salut für Caudwell reshaped the way I hear timbral experimentation and gesture in general on the instrument, and really opened my ears (and perhaps challenged some biases), while working on highly specific traditional notation in music by composers like Babbitt pushed me to be much more aware of that level of specificity even in scores that don’t notate it explicitly. I think I could come to similar conclusions about other kinds of playing, from improvising, to process-based Minimalism and to music where the guitar is providing a rhythmic foundation. Despite aesthetic differences, I find that all music has the potential to inform my approach to other kinds of music in surprising and gratifying ways.

Not primarily thinking of myself as a composer, I feel a little strange thinking about how my compositional style has evolved. But if I’m able to have any objectivity about it, I’d say that as I’ve studied, performed, and been exposed to more repertoire and performing experiences as a guitarist, I think those aesthetic ideas have seeped into some of what I have written, or at least what I’m hearing and trying to articulate when I write new music.

Is the frequently expressed idea of finding one’s own “voice” as a composer important to you?

I’ll answer from the perspective of finding one’s voice as an artist, since I think I am more qualified to talk about this generally. I think it’s important to know who we are and what resonates with us, so that we can approach our art honestly. But sometimes actively seeking out one’s voice can risk becoming overly self-conscious, at least for me. We can’t help but be who we are as artists and as people, so I don’t necessarily think it always requires a special effort to find one’s voice so much as allowing it to be present. While some artists gravitate toward specializing either in their compositional language or their performing activities, others cast a wider net, trying out different frames or contexts. I count myself in the latter camp, as I’ve always been interested in playing and making a wide range of music. But regardless, I think an artist’s personality tends to show through either way, and while honing and refining what one has to say is of course crucial to growth, there is a certain degree to which an artist’s “voice” is something that is more apparent to others than to artists themselves.

Turning to New Focus, you’ve described it as “an artist-led collective label featuring releases in contemporary creative music of many stripes, as well as new approaches to older repertoire.” Does “collective” mean that each of the members collaborates in the funding and direction of the label?

The extent to which it is a collective is that artists retain control over their own projects to a large degree, as opposed to a collective management of the label as an operation. Each project is different and comes with a different set of factors in terms of funding, production planning, etc., but the vision of the label has always been to create a space where artists are making and curating their own recordings. While many of the submissions that come in to the label are referred by past artists who have released with New Focus, there isn’t any collective activity governing catalog approval or overall label management. So my use of the word “collective” might be misleading—I think my intent was simply to indicate that artists’ agency over their own projects is a priority, and to acknowledge the contributions of an amazing community of artists.

You cofounded New Focus with Peter Gilbert and Ryan Streber. How did you all meet? When did you decide to create your own label?

I met Peter Gilbert while we were master’s students at the Cleveland Institute of Music; he was a composition major and I was a guitar major. We worked together on directing the Mostly Modern Chamber Music Society, a small chamber music series featuring contemporary music in Cleveland that was active from 1999 to 2003. After both of us moved to the East Coast to do our doctoral degrees, we continued to collaborate on new pieces and projects. Peter composed Ricochet for guitar and electronics for one of my doctoral recitals at MSM, as a companion piece to Mario Davidovsky’s Synchronisms #10; Davidovsky was also Peter’s teacher at Harvard. Recording Ricochet, Synchronisms #10, and Nils Vigeland’’s La Folia Variants was the impetus for the first New Focus album, Resonance, which was an album of contemporary guitar repertoire that Peter and I coproduced in 2002 at the Harvard Music Department Electronic Music Studio.

I had met Ryan Streber through a new music quartet that I was a member of, Flexible Music, when Ryan recorded a demo for us in 2002. He was studying with Milton Babbitt at Juilliard and had recently become very interested in recording. Ryan joined the Resonance project for some editing and post-production, and the team was born. When it came time to release the album, Peter and I decided to slap a label name on the packaging, not entirely knowing at the time what the future implications might mean. Several of the next albums on the label involved all three of us on the production team.

Who were your colleagues in Flexible Music?

Flexible Music—Haruka Fujii, percussion; Eric Huebner, piano; Tim Ruedeman, saxophones; myself, guitars—was a New Music quartet that was active from 2002 to around 2014. The group recorded two pieces for my album Sustenance, which was the third release on the label and featured chamber repertoire for guitar. After that release, the quartet started to plan a full album of music written for us, which became FCR105, FM, and included music by Vineet Shende, Nico Muhly, John Link, Orianna Webb, and the piece that inspired our formation, Louis Andriessen’s Hout.

Meanwhile, starting in early 2006, I had begun to play with the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), which was an exciting group primarily based in Chicago that had started to establish a presence in New York. We developed a series of pieces that included guitar and subsequently recorded FCR104, Abandoned Time, which included recordings of pieces by Kaija Saariaho, Magnus Lindberg, Du Yun, Dai Fujikura, and Mario Davidovsky.

After releasing both of those projects, members from Flexible Music and ICE approached me about releasing their own recordings, something I hadn’t yet considered up to that point. So I had to consider what it would mean to release recordings that I was not performing on, or in some cases not involved with in a production capacity either. That was the beginning of building what ultimately became the broader label business of New Focus Recordings beyond my own projects.

Had you recorded for other labels before founding New Focus? If so, was that a less than satisfying experience, giving rise to your desire to “have creative control over all elements of the recording and post-production process?”

I had only released one self-produced album that was not on a label prior to the first New Focus project. So I wasn’t responding to any less than satisfying experience so much as recognizing that given the way the industry worked at the time, it would not have been accessible to me as a graduate student with limited resources to release with an established label.

As you’ve alluded to just now, New Focus now markets a variety of different labels. What prompted this expansion?

As New Focus grew, I saw the need to make internal distinctions within the catalog for various reasons. ICE’s TUNDRA imprint was a way to delineate albums that were clearly produced from within the infrastructure of what was a fast-growing and increasingly highly visible organization in the music world. The SEAMUS [Society for Electro-Acoustic Music in the United States] catalog is an archive of new and back-catalog recordings produced and curated within the SEAMUS organization, supporting electronic music composers. Minabel Records is composer Dai Fujikura’s own imprint for his compositions and recordings, and he handles all the production and post-production for those releases himself. Furious Artisans is co-directed by Marc Wolf and Jeremy Tressler—Marc Wolf has been the New Focus webmaster and primary album designer since around 2010, and his label needed a distributor, so it was a natural fit for us to facilitate this. We have collaborated with Furious Artisans in various capacities since then, distributing their catalog and sometimes working more closely on releases. Olde Focus is directed by ICE cellist and viola da gambist Kivie Cahn-Lipman, and features premieres of newly discovered early music scores.

Are New Focus albums available through streaming?

Yes. New Focus has been distributed by Naxos of America since 2012; it distributes our digital catalog worldwide and our physical catalog within North America. New Focus sells digital downloads via retail sites like iTunes, Presto Music, and Amazon, as well as through our website and Bandcamp, and our catalog is streaming on all the major platforms.

Why did you choose Adjacence as the title for your latest release?

I started with a closely related title, Adjacent Path. I adjusted it to Adjacence, which isn’t technically a word as far as I’m aware, because I have a few contemporary music albums with similar titles, Resonance and Sustenance. I saw this album as related to those other two in the sense that it is a collection of music which might not be superficially connected in terms of all the pieces belonging to one aesthetic or another, but which has an internal cohesion that I discovered while thinking more deeply about how the music worked together to form a whole. Aside from that, I’ve felt often over the last several years that there are some fairly strong polemical narratives in different corners in the contemporary music world that I’m simultaneously sympathetic to, while also not being 100 percent aligned with. So I’ve done my best to carve out what felt at times to me like an “adjacent path” for myself, walking alongside and feeling affinity for various aesthetic stances without necessarily being an uncritical member of any particular camp. I’m sure to a certain extent a lot of artists have instinctively found themselves in a similar position. I guess this is how I expressed it to myself, and it felt like it fit well with the curation on the album.

Having heard the music, I have to agree that the pieces don’t “superficially” adhere “to one aesthetic or another”; there’s considerable stylistic variety on display.

Extending on the notion of pursuing an “adjacent path,” I have always been attracted to a lot of different kinds of music-making, going back to my first years of studying the guitar. So the proximity on this album of modernist works by Charles Wuorinen, Mario Davidovsky, and Carl Schimmel, experimentation with timbre and pitch by Ken Ueno, Peter Adriaansz, and Bernadette Speach, more lyrical playing in pieces of Peter Gilbert, Sidney Boquiren, and Tonia Ko, and different kinds of integration of improvisation in pieces of Tyshawn Sorey and Tania Leon, all feel like different but related sides of my overall practice, even if they are very diverse stylistically. On top of that, several of those composers themselves are also engaged with a range of musical practices as well, beyond the frame of the pieces recorded on the album. That, and the fact that a lot of these types of music-making have become common practice in the lives of contemporary instrumentalists, led me to want to curate an album where they all lived together.

How do you decide what to record?

For my own recording projects, I think a variety of factors come into play, but primarily, the music I include tends to grow from relationships I’ve been lucky to cultivate with composers or other players. I feel a certain obligation to document the fruits of these collaborative relationships, I think both for the composers but also maybe for myself, a kind of chronology of what I have been doing artistically.

In general, I’m also very invested in the idea of documenting pieces for the guitar, whether they be solo or chamber works, that I feel are significant and can add in some meaningful way to the repertoire. But I also just find that there are some pieces in which I have invested, in that feel as if they deserve a recording, usually both because of the material itself but also because of the place that they have occupied in my own musical life. When I look at the track list for Adjacence, certain pieces jump out for the experiences I had performing them with colleagues and seeing them develop as pieces and as interpretations. Tyshawn Sorey’s Ode to Gust Burns, for instance, was one of the first of his many collaborations with the International Contemporary Ensemble and a landmark of the group’s ICE Lab program. Carl Schimmel’s The Alphabet Turn’d Posture Master was one of my favorite works written for the Flexible Music quartet; our recording hadn’t found its way onto another album, and it felt like it fit really well here. Ken Ueno’s Ghost Flowers is a piece that represents my growing interest in microtonality and alternate tunings, and I had been planning on recording it for several years. Whenever I have a chance to feature Peter Gilbert’s music I am thrilled, as we have been close colleagues for so many years. Neñia, which features the wonderful soprano Elizabeth Weigle, is a piece that I was very grateful to capture in the studio and include on this album, and I think it brought a lush lyricism and expressivity to the program that isn’t necessarily out front in many of the other pieces. Peter Adriaansz’ Serenades and Charles Wuorinen’s Electric Quartet are very different, but both are major contributions to the repertoire for music for multiple electric guitars.

Do you still perform?

Yes, I’m still very active as a performer, playing a lot of contemporary chamber music particularly, as a freelancer with several groups, and as a member of the International Contemporary Ensemble and the New Music ensemble counter)induction, and I play solo performances from time to time as well. I feel lucky to have been able to balance being involved in contexts where the focus is on substantial music for the guitar, either in chamber or solo settings, as well as ones in which the guitar is involved in larger projects, even if it understandably plays a more integrated role in those pieces.

Is there much of an audience for New Music? A loyal fanbase? Any ideas for how to expand it?

I do think there is a decent-sized audience for contemporary music, and it’s been growing over the last several years. Of course, the most adventurous repertoire will always tend to live on the fringes, but to a certain extent I feel like I’ve seen contemporary music gain a foothold more and more in the mainstream of classical music in the last two decades. I think there are a lot of advocates for the music who are doing great and creative things to expand the audience and reach out to new listeners, whether it be integrating elements of more popular styles or incorporating multi-media or other disciplines into performances.

I have found that I’m able to program pretty esoteric music in concerts for general audiences as long as I speak about the piece a bit to the audience, give them something to hold on to, and commit to it in my performance as music with the same expressive investment as any other repertoire. Since I really love this repertoire, that doesn’t feel like a chore to me; it feels natural and honest.

I think overall that New Music is such a broad term, and tells us more about the micro-economy it exists in than it does about what the music actually sounds like. I think this is ultimately a good thing, and results in a wonderful diversity of styles and sounds under the New Music umbrella. But that said, in my mind there’s a distinction between being an advocate for the ideals of contemporary music versus all of new music itself. Just as in any other era, there is a wide continuum of music being written and performed; some of it will stand the test of time, and other works deserve a solid hearing but might not become lasting pillars of the repertoire. Part of the job of those of us who are in the field is to provide pieces with that platform and then participate in and allow the process of evaluation to happen naturally over time.

From an ideological point of view, I was drawn to contemporary music as a student because of a conviction that a concert music world that didn’t center, or at least celebrate equally, the music of its own time would be inherently out of balance. It goes without saying that during Bach’s time, Mozart’s time, Beethoven’s time, etc., most music that audiences heard was newly composed music. But as the inheritors of this grand tradition (and so many others from around the world of course) and with the prevalence of recording technology, we have this rich trove of an almost museum-like archive of musical history that we can revive, and an industry which survives through that revival. That’s absolutely an amazing gift and we should be grateful for it. But while Bach still has so much to say to us about being human in any era, he can’t say anything specific to us about the unique experience of being human in 2025. So to the extent that art’s role is to elevate and help us understand our lives in a deeper way, we need the voices of contemporary artists to be part of the kind of conversation that can only exist in artistic spaces, one in which abstractions are sometimes better suited to illuminate core truths.

Have you performed in schools to expose children to contemporary music?

Yes, and it’s very gratifying. I find that children especially respond very well to contemporary music, often because they don’t have the prior knowledge to put any music in boxes to begin with. So they are just listening and responding to only what they hear, without comparing it to what they expect.

That’s an ideal state of mind with which to approach Adjacence, which offers listeners a smorgasbord of potentially unfamiliar sounds.

One of the enjoyable aspects of playing a lot of contemporary music on electric guitar, which is a fairly significant portion of the repertoire I play, especially in chamber settings, is the ever-growing battery of effects that are available to modulate the sound. On Adjacence, Peter Adriaansz’s Serenades makes extensive use of the ebow (a sort of electronic bow that uses magnets to sustain the guitar tone), delay, and distortion pedals. I used various combinations of those effects as well in some of the improvised sections of Tania León’s Ajiacoand Tyshawn Sorey’s Ode to Gust Burns, as well as a short section where I looped some material with a loop pedal. Carl Schimmel’s The Alphabet Turn’d Posture Master calls for a subtle delay effect in two sections. In the Wuorinen Electric Quartet, there are a couple of surprising and subtly humorous passages where he uses the whammy or tremolo bar to lower the pitch.

Since some of the pieces incorporate microtones. I was wondering how to play them on the guitar: unusual tunings, movable frets?

Both! Ken Ueno’s Ghost Flowers employs a unique tuning based on the overtones of a detuned low C-string, but it is played on a normal equal-tempered fretted guitar. I’ve played several pieces and written a couple as well that arrive at microtonality simply by retuning the open strings either to quarter-tones or some other microtonal division. I recorded my most recent Bach album, Aufs Lautenwerk, in a Baroque-period temperament using microtonal guru John Schneider’s moveable-fret Vogt guitar, in which each fret can be adjusted at each string to adhere to a fixed tuning system. More recently, I bought a great instrument from a company called Microtone Guitars: It has replaceable fretboards that are held in by magnets and can be swapped in less than 30 seconds. So I have fretboards in a few different tunings that I have been experimenting with.

Was the music on Adjacence conventionally notated?

Almost all of it is written in conventional notation. Two movements of Sidney Boquiren’s piece are written in proportional notation, with the different extended technique events in the various instruments indicated spatially within the time frame of the given section. The pieces that involve improvisation have different strategies for indicating that in the score. In the Sorey, the improvising is meant to be based on the materials in other sections of the piece, while the León is notated with different repeated boxes of material and a structural road map. In the latter, pianist Cory Smythe and I took some liberty with that score and treated it as a structural improvisation, adding quite a bit of our own material alongside the music in León’s original score. Utopian Prelude is a mix of notated material and improvisation over a pre-recorded loop, and Dystopian Reprise is an improvised solo over an excerpt from one of the movements of Adriaansz’s piece. But aside from those, all the other pieces are written in conventional notation, with any needed additional information about special techniques or tunings written into the score.

Vis-à-vis your Bach album, does it ever feel disorientating moving from Bach to New Music and vice versa?

I suppose occasionally it can involve a kind of mental gear shift, but I would say in general I don’t feel that much dissonance switching between Bach and a lot of contemporary solo repertoire. In fact, Bach and a lot of modernist repertoire seem to me to have more in common with each other than not: In both cases there is an unfolding argument being built out of pitches and rhythms, and one can track the narrative of the piece by listening to those melodic, gestural, and harmonic relationships. A bigger shift would be from the kind of contemporary chamber music on electric guitar that is focused on timbral sculpting, for instance, to Bach, where the pace of evolution in the music and the way into its expressivity are really very different from each other.

Your Bach album reminds me that in addition to contemporary music, New Focus supports “new approaches to older repertoire.”

It’s been exciting to delve into repertoire from the canon and explore it through a different lens and new approaches. For instance, on the album Song Cycle, I recorded several Schubert Lieder arrangements both for soprano and guitar (with the excellent Tony Arnold) and in solo versions (by 19th-century guitar composer Johann Kaspar Mertz) on a replica of a 19th-century instrument. It was a great experience studying those scores, both in the duo versions and solo versions, and really examining the relationship between text and music, one of the many components of Schubert’s songs that really sets them apart as masterpieces. I mentioned earlier the Aufs Lautenwerk recording I co-produced with John Schneider of MicroFest Records. Playing Bach’s solo music in period temperaments had been a dream of mine since graduate school; it opened up a whole world of pitch subtlety and color, and changed how I thought of modulation and harmonic return in Bach’s music.

The excellent four-hands piano duo, Duo Stephanie & Saar, has released several recordings of arrangements of iconic works for their ensemble on New Focus, and I was grateful to be involved as a coproducer on their fascinating and beautiful recording of Beethoven’s op. 130 String Quartet for four-hands piano, as well as their renditions of Bach’s The Art of Fugue and Győrgy Kurtag’s Bach chorale arrangements. I think this is really one of the strengths of the recording process, the opportunity to spend the time to really think carefully about how you want to approach repertoire, and then use the studio as a tool to realize that interpretation. So while repertoire from the core canon isn’t the focus of New Focus, pun intended I suppose, there are some notable projects that are great to have in the catalog.

How extensive is that catalogue?

We have 352 releases in the main catalog of New Focus, and then an additional 139 across the various other imprints.

What does the future hold for both you and New Focus?