Abandoned Time was the International Contemporary Ensemble's second full length cd, and the first entirely programmed and curated by members of the group. It features several pieces that have become core parts of ICE's repertoire, and highlight the group's energetic, physical style of playing. The physicality of the music binds the program together, as the five pieces eschew dogmatic schools of composition in favor of intuitively driven, sensual approaches to sound and energy.

| # | Audio | Title/Composer(s) | Performer(s) | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time | 59:26 | |||

| 01 | Abandoned Time | Abandoned Time | International Contemporary Ensemble, Daniel Lippel, electric guitar, Matthew Ward, conductor | 8:52 |

| 02 | Festino | Festino | Daniel Lippel, guitar, Kivie Cahn-Lipman, cello, Maiya Papach, viola, Randy Zigler, bass | 10:18 |

| 03 | Adjö | Adjö | Tony Arnold, soprano, Claire Chase, flute, Daniel Lippel, guitar | 10:33 |

| 04 | Visissitudes No. 1 | Visissitudes No. 1 | Cory Smythe, piano, David Reminick, saxophone, David Schotzko, percussion, Kivie Cahn-Lipman, cello, Daniel Lippel, guitar, Randy Zigler, bass | 14:19 |

| 05 | Linea d'ombra | Linea d'ombra | Claire Chase, flute, Daniel Lippel, guitar, Joshua Rubin, clarinet, David Schotzko, percussion | 14:58 |

THOUGHTS ON THE REPERTOIRE

ICE's relationship with Dai Fujikura traces back several years, and it is a special one. Dai was one of the first winners of ICE's Young Composer Call for Scores, an international solicitation that has been at the core of ICE's mission as an organization. As Dai's career skyrockets in Europe and across the world, we at ICE can happily say we knew him when. In 2005, we learned that Dai had a piece for electric guitar and ensemble that had yet to be performed in the United States. ICE performed the piece in Chicago in May 2006, and Dai came from London to attend the performance and rehearsals. It was a fantastic experience for us, and the idea for this recording was actually launched at Schubas Tavern on the North Side over late night beers after the concert. Abandoned Time is one of the only pieces I know to truly integrate rock guitar and chamber ensemble in a modernist aesthetic. It clearly uses rock techniques, but does so in a language that eludes guitar cliches. One key decision Dai made in balancing these worlds was to amplify each instrument in the ensemble in performance. The quality of an amplified sound versus an acoustic sound is quite different spatially and sonically, so micing the acoustic instruments really helps to homogenize the sound of the ensemble with the electric guitar. We achieved a similar effect in the recording by putting up a battery of close microphones on the ensemble to blend with the microphones further back in the hall. In fact, during the mixing process of the recording, Dai consistently asked for more of the close mics, pushing the boundaries of a "realistic" sounding recording. We obliged, at first hesitantly and then with more enthusiasm, as the process began to reveal that this hyper-real sound world was central to the impact of the piece. One of the primary motives driving the piece is the volume swell. It shows up in several incarnations: in the distorted guitar swells, in the breathy ensemble sighs, and later, in the coda, in the strings steady modulating underneath the plaintive guitar. Is the "abandoned time" of the piece its yearning end? Or is it the inexorable build up to the climax, when all restraint is abandoned in the face of a wave of energy? Perhaps it is both, but in considering "Abandoned Time" for the title of the recording, we realized that each piece on the album ends quietly, despite their considerable activity levels. Maybe there is a realization that we are abandoning time every moment, whether we are throwing ourselves full throttle into physical catharsis, or reflecting pensively afterward. Or maybe it's just a cool sounding name for an album.

Read MoreFestino is an ideal window into Mario Davidovsky's style. It contains all of the facets of his characteristic voice: rhythmic ingenuity, constant equalization of extreme expressive worlds, flaunted expectations, and an internal identity struggle within the piece. Davidovsky wrote Festino shortly after finishing his first guitar piece, Synchronisms #10 for Guitar and Electronic Sounds. In both instances, he creates a larger-than-life guitar, with the tape sounds in the Synchronisms and with the string trio in Festino. Davidovsky is well known for his pioneering role in the world of electronic music, as the composer of the Synchronisms series and as a path-breaking faculty member at the Columbia University Electronic Music Studio. As much as Davidovsky is associated with electronic music, he has never been a technocrat; his interest in technology was strictly driven by a desire to achieve musical means than he felt were not possible with acoustic instruments. In many of his more recent acoustic works, like Festino, he brought the language of electronic music full circle, incorporating characteristically electronic gestures into his acoustic writing. The tightly coordinated rhythmic machines that punctuate so many of the phrases in Festino are an outgrowth of this retranslation. More often than not, these quirky ensemble mechanisms are used in a wry, comical context, frequently to break the tension of a serious passage. Davidovsky's expressive world is meticulously balanced. Moments of raw emotion are balanced by clever humor. Moments of visceral impetuosity are balanced by poignant nostalgia. As Davidovsky related in an interview, "I have this kind of valve inside, it's almost automatic inside myself, I am always two places at the same time, or nowhere." His music reflects this simmering existential anxiety--how can we construct uncomplicated identities when we live in such a complicated age?

Throughout his body of work, Davidovsky flaunts expectations, particularly with respect to his handling of instrumentation. In his Synchronisms for percussion ensemble, he flaunts the expectation of a loud drum ensemble but avoiding non-pitched percussion for almost the first half of the piece, opting instead to emphasize quite rolls on mallet instruments. In the guitar Synchronisms, the tape part doesn't enter until five minutes into the piece, long enough for the listener to forget that it's an electro-acoustic work. Similarly, in Festino he effectively neuters the low string trio (viola, bass, cello) by asking the players to imitate the guitar with plucks, pops, and body hits (watch out vintage Cremona viola!). He saves the more traditional string writing for string tutti sections without guitar, which alternately explode with pathos (timing) and whisper with a mournful calm. The string trio augments the guitar to create a hybrid instrument, "a big guitar", mirroring the role of the electronic part in Synchronisms #10. The texture emphasizes accents, and diminishing decays, just as the guitar's sound is loudest at the attack and decays immediately. Davidovsky calibrates his use of the ensemble based on his goals for the piece, reinventing the string trio in the process.

In some ways, Davidovsky's music is very traditional. It proceeds linearly, introducing motives that develop and later reconcile with each other. What is new in his narrative process is how he juggles several "strata" in the piece, almost as if the protagonist is struggling with multiple identities all inside one personality. "I will begin the piece, more often than not, with a statement like a motive. I try to make a statement like how Beethoven would present a theme in a symphony-- very consistent and cohesive and natural and elegant. In my case, I construct that kind of statement out of motives that are essentially very different from each other. You could say that each of those motives have their own implied rhythm, their own implied harmony, even character. Then what I do, more or less looking back at Beethoven, I take those motives, and actually generate a different piece of music. Instead of voice leading things, I will develop a strata. You could say that Carter does that stratification as well, but the difference is that Elliot seems to talk about each instrument as a different person. In a way, my stratification involves one person telling four stories-- the one person is the remnant of the voice leading. What I like to think I do is develop a trajectory for each of those motives, it's almost like super glorified voices that develop a simultaneous story-- though they might seem completely unrelated, eventually the four voices come together." Festino is a perfect example of this stratification of motives, indeed, of multiple "stories" within a piece. The juggled identities in Festino include several moods: clever/clownish, melodramatic/passionate, awkward/apologetic, nostalgic/wistful, and focused/resolute. In almost all of these passages, the primary motive of the piece, the short three-note figure that opens the work in the viola appears, dressed in different expressive garb. This little motive (the same motive that drives Synchronisms #10 in fact) is the part of oneself that we carry through all the different spaces of our lives. As we wear many hats, that core marker of our persona shifts, but it is never left entirely behind. This style of stratification is a hallmark of Davidovsky's music, and allows him to musically capture something about the layered process of how the mind works, and how we perceive our complicated identities. The title "festino" refers to a work like a serenade, with the character of an opera buffa perhaps. I've often felt that Davidovsky's Festino is a deep portrait of a clown, with the virtuoso trickster outside hiding the loneliness and longing underneath. It was recently pointed out to me that the piece would work in collaboration with a live performance by a mime. I totally agree. Anyone know a great mime?

It is interesting to compare the two Finnish pieces on the recording, Linea d'ombra and Adjo. Both place considerable emphasis on extended techniques; percussive effects on the instruments, extra percussion instruments on stage, a large role for key-clicks on the wind instruments, vocalizations for the instrumentalists as well as the soprano. They also use text in a similar way, often fragmenting words into syllables and milking them for their sonic effect even if it risks obscuring their meaning. Even the use of the guitar is similar--both pieces employ an alternate tuning of the bottom string to Eflat, a fairly rare scordatura.

That said, the two works could not be more different. While Linea is extroverted to the point of occasional aggression and brashness, Adjo is sensuous and introverted. The same percussive techniques that are punctuated in Linea are lyrical in Saariaho's piece. The work is divided into three large sections, with a concluding coda. The first section is taut and rhythmic, with a lilting triplet motive that seems to float in the air at the extremely slow tempo (quarter=30). Phrases come out in little starts and stops, as if they are being stifled by an arctic cold. The soprano's bursts of fragmented text are mirrored in the soft whispers in the flute part, as if they have been picked up by the wind. A spacious guitar solo follows, most notable for the intensity of its silences and the white noise background provided by flute and sandblock. The voice reenters gloriously, finally soaring in the high register with freedom. The ice from the early section seems to have melted, at least enough for the lyricism of the piece to become full-throated and long-lined. In contrast to the rigorous rhythmic notation of the opening, this entire section employs graphic notation, with events occurring variably one after another, instead of relating to a fixed pulse. The choice of a loose rhythmic notational style for this section licenses the performers to inject an expansive sense of liberation into these phrases. After a soaring vocal climax, there is a far away coda, on the syllable "ah". We used some very mild recording trickery here--Tony Arnold turned her back to the hall to recreate the otherwordly effect.

Du Yun has been an integral part of ICE since its inception at Oberlin Conservatory in 2000. Not only has she written countless works for ICE and its members, but she has served on the group's advisory board and as a composer-in-residence for years. She has had an enormous influence on the creative direction of the ensemble, and the group's willingness and enthusiasm for taking artistic risks. The working relationship that ICE has cultivated with Du Yun is unique. As a group, ICE generally is interested in getting beyond the surface of the notation, and inside the composer's motivations for their musical choices. With Du Yun, the group has been able to take that one step further, as the notation is primarily a springboard for the all-important last stage of composition--that stage that happens between composer and performer during working sessions. Du Yun brings her sound out of players, through singing, wild gestures, and the sheer force of her personality. While it's not implicitly stated, it is always clear from working with her that the player should bring something of her energy to the piece. And so, even though there is some wiggle room left for the players to interpret portions of Du Yun's scores, all of her pieces have the immediately distinguishable mark of her artistic voice. This belief in the artistic value of the collaborative process, to say nothing of the communal one, is one of the reasons that the relationship between Du Yun and ICE has remained so exciting for so many years. Vicissitudes no. 1 was first written while Du Yun was a doctoral student at Harvard and the Bang on a Can All Stars came to Cambridge to do a residency with the student composers-- hence the unusual instrumentation (originally) for guitar, bass, cello, piano, clarinet, and percussion. Du Yun created an optional version with saxophone which became ICE's staple performance line-up for the piece. The piece actually features three instruments prominently: the saxophone, percussion, and guitar. The saxophone is given the role of projecting the emotional desperation that pervades the piece. The wails and cries on the sax are set off by frenetic improvised lines, almost in a "free jazz" vein (in quotes because the term "free jazz" doesn't really describe a sound... or at least by definition it shouldn't). The percussion part, with its piercing cowbells and primal tom-toms, lays the foundation for the persistent anxiety expressed by the other instruments. In performance, the guitarist waits off stage for the first half of the piece, and comes on after the dramatic percussion solo. The first few notes of the guitar solo radiate a centered wisdom previously unheard in the work. Du Yun mentioned that she was intentionally evoking East Asian plucked string instruments in this passage, specifically the Japanese shamisen and later the Chinese pipa. The contrast of these simple phrases meant to evoke ancient instruments with the stridency of the earlier material in the other instruments is striking, and focuses this moment in the piece. It is as if the timeless lessons of tradition are being offered as salvation from desperation and alienation. As the guitar solo unfolds, however, it is swept up in an uncontrollable frenzy of its own, washing away any salvation in a tsunami of energy. The ensemble returns later, as a stain washing over a wound, and the piece ends much as it began, with a profound sense of dismay.

In many ways, the overall concept for the album Abandoned Time grew out of ICE's relationship with Magnus Lindberg's Linea d'ombra. The process of learning, performing, and eventually absorbing this piece was a challenging and perpective-shifting experience for the ensemble, and came to embody a certain raw, physical style of performing new music that has become a hallmark of ICE concerts. One thing that an audio recording sadly cannot capture is how visually dynamic this Lindberg piece is in performance. The individual parts in themselves are quite virtuosic, so watching a performance is a little like watching a high wire act, or a boxing match (depending on your inclination).The piece not only is instrumentally demanding, it makes demands beyond the instruments themselves; the clarinetist and guitarist flail maracas and sandblocks in the air, drawing out every drop of sound; the flutist and clarinetist feverishly click the keys of their instrument creating unsettling insect-like noises, all four players put aside their modesty and turn their voices into sonic weapons in a panoply of vocal techniques (full-throated screaming, punctuated shouts, palatal clicks, meditative chants, and syllabic whispers in a hybrid of Finnish, Italian, and gibberish). During the clarinet cadenza, the other three players gingerly leave their places, and converge on a face-up tam-tam cymbal. In the ICE performance of this work, the tam-tam is set on the front of the stage in the corner, to suggest that this section of the piece is delivered as from a podium, perhaps as a reflective soliloquy. The jangly tam-tam fanfare after the clarinet cadenza (ca. 12:10) is played by the percussionist, guitarist, and flutist, as they huddle around the large cymbal. Lindberg mischievously writes several mallet changes for all three parts here, so the flutist and guitarist learn a bit what it is like to be a percussionist, as they scramble to switch between wood, rubber, and metal sticks, chains, and cardboard tubes. Eventually, stage whispered gibberish syllables take over, and the piece ends with a fragmented reading of a mysterious passage from an Italian poem by Walter Valeri: "Sorridi, sospira, sospendi la morte, giura che un melo di freddo da fiori stasera" (Laugh, sigh, defy death, but be warned that the apple tree of cold will bloom tonight). When ICE worked with Lindberg in preparation for our Miller Theatre performance of Linea, he was reluctant to offer any facile explanation for why he chose these words. My interpretation (though it may be facile) is that there are an admonition that the youth, freedom and liberation that the piece celebrates don't cease the flow of time. The cold apple tree will bloom, we will get old and die, etc...

Linea d'Ombra is musically idiosyncratic in many ways. One of its unifying characteristics, for instance, is that the four players only play in rhythmic unison on a couple of occasions in the work. Instead, many of the close ensemble moments are deliberately notated in such a way that the players play ever so slightly apart. Perhaps this is a reference to the title, which translates to "shadow line", as the instruments shadow each other closely throughout the piece, but in any event it contributes to the sense of organized chaos. The four lines in Linea are all vying for prominence; no clear primary or accompanimental voices emerge. The three solo cadenzas in Linea give the listener a chance to focus on the specific personalities of the instruments and their players. All in all, Linea is a charisma driven piece, from its composition to its performance.

-Dan Lippel

Executive producers: Daniel Lippel and Claire Chase

Engineered, Edited, and Mastered by Ryan Streber

Session Producers: Peter Gilbert (Lindberg, Saariaho, Du Yun) and Jacob Greenberg (Davidovsky, Fujikura)

Editing Producers: Daniel Lippel (Fujikura, Lindberg, Davidovsky) and Jacob Greenberg (Saariaho, Du Yun)

Score supervision: Peter Gilbert (Davidovsky), Jacob Greenberg (Lindberg, Saariaho)

Recorded 1/07, 7/07, and 8/07 in Sweeney Auditorium, Smith College, Northampton, MA except Vicissitudes No. 1 which was recorded in Paine Hall, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA on 3/07.

"Abandoned Time" was partially funded by a grant from FIMIC, the Finnish Music Information Centre.

Mix supervision: Daniel Lippel, Jacob Greenberg (Saariaho)

Liner Notes by Daniel Lippel and Peter Gilbert

Design by Aaron David Ross

Cover image by Roma Koshel

Personnel:

Fujikura: David Bowlin, violin; Maiya Papach, viola; Katinka Kleijn, cello; Randall Zigler, bass; Claire Chase, flute; Joshua Rubin, clarinet; David Schotzko, percussion; Cory Smythe, piano; Daniel Lippel, electric guitar; Matthew Ward, conductor

Davidovsky: Kivie Cahn-Lipman, cello; Maiya Papach, viola; Randall Zigler, bass; Daniel Lippel, guitar

Saariaho: Tony Arnold, soprano; Claire Chase, flute; Daniel Lippel, guitar

Du Yun: David Reminick, saxophone; David Schotzko, percussion; Cory Smythe, piano; Randall Zigler, bass; Daniel Lippel, steel-string guitar

Lindberg: Joshua Rubin, clarinet; Claire Chase, flute; David Schotzko, percussion; Daniel Lippel, guitar

Celebrated as a “luminary in the world of chamber music and art song” (Huffington Post), Tony Arnold is internationally acclaimed as a leading proponent of contemporary music in concert and recording as a “convincing, mesmerizing soprano” (Los Angeles Times) who “has a broader gift for conveying the poetry and nuance behind outwardly daunting contemporary scores” (Boston Globe). Her unique blend of vocal virtuosity and communicative warmth, combined with wide-ranging skills in education and leadership were recognized with the 2015 Brandeis Creative Arts Award, given in appreciation of “excellence in the arts and the lives and works of distinguished, active American artists.” Arnold’s extensive chamber music repertory includes major works written for her voice by Georges Aperghis, George Crumb, Brett Dean, Jason Eckardt, Gabriela Lena Frank, Josh Levine, George Lewis, Philippe Manoury, Carlos Sanchez-Gutierrez, Christopher Theofanidis, Ricardo Zohn-Muldoon, John Zorn, and numerous others. She is a member of the intrepid International Contemporary Ensemble and enjoys regular guest appearances with leading ensembles, presenters, and festivals worldwide.

With more than 30 discs to her credit, Arnold has recorded a broad segment of the modern vocal repertory with esteemed chamber music colleagues. Her recording of George Crumb’s iconic Ancient Voices of Children (Bridge) received a 2006 Grammy nomination. She is a first prize laureate of both the Gaudeamus International and the Louise D. McMahon competitions. A graduate of Oberlin College and Northwestern University, Arnold was twice a fellow of the Aspen Music Festival as both a conduc- tor and singer. She currently is on the faculties of the Peabody Conservatory and the Tanglewood Music Center.

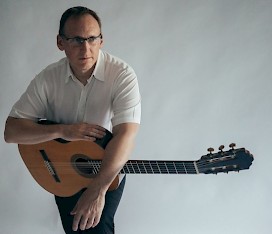

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

With a commitment to cultivating a more curious and engaged society through music, the International Contemporary Ensemble – as a commissioner and performer at the highest level – amplifies creators whose work propels and challenges how music is made and experienced. The Ensemble’s 39 members are featured as soloists, chamber musicians, commissioners, and collaborators with the foremost musical artists of our time. Works by emerging composers have anchored the Ensemble’s programming since its founding in 2001, and the group’s recordings and digital platforms highlight the many voices that weave music’s present.

Acclaimed as “America’s foremost new-music group” (The New Yorker), the Ensemble has become a leading force in new music throughout the last 20 years, having premiered over 1,000 works and having been a vehicle for the workshop and performance of thousands of works by student composers across the U.S. The Ensemble’s composer-collaborators—many who were unknown at the time of their first Ensemble collaboration—have fundamentally shaped its creative ethos and have continued to highly visible and influential careers, including MacArthur Fellow Tyshawn Sorey; long-time Ensemble collaborator, founding member, and 2017 Pulitzer Prize-winner Du Yun; and the Ensemble’s founder, 2012 MacArthur Fellow, and first-ever flutist to win Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Prize, Claire Chase.

A recipient of the American Music Center’s Trailblazer Award and the Chamber Music America/ASCAP Award for Adventurous Programming, the International Contemporary Ensemble was also named Musical America’s Ensemble of the Year in 2014. The group has served as artists-in-residence at Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival (2008-2020), Ojai Music Festival (2015-17), and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (2010-2015). In addition, the Ensemble has presented and performed at festivals in the U.S. such as Big Ears Festival and Opera Omaha’s ONE Festival, as well as abroad, including GMEM-Centre National de Création Musicale (CNCM) de Marseille, Vértice at Cultura UNAM, Warsaw Autumn, International Summer Courses for New Music in Darmstadt, and Cité de la Musique in Paris. Other performance stages have included the Park Avenue Armory, ice floes at Greenland’s Diskotek Sessions, Brooklyn warehouses, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and boats on the Amazon River.

The International Contemporary Ensemble advances music technology and digital communications as an empowering tool for artists from all backgrounds. Digitice provides high-quality video documentation for artist-collaborators and provides access to an in-depth archive of composers’ workshops and performances. The Ensemble regularly engages new listeners through free concerts and interactive, educational programming with lead funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Curricular activities include a partnership at The New School’s College of Performing Arts (CoPA), along with a summer intensive program, called Ensemble Evolution, where topics of equity, diversity, and inclusion build new bridges and pathways for the future of creative sound practices. Yamaha Artist Services New York is the exclusive piano provider for the Ensemble. Read more at www.iceorg.org and watch over 350 videos of live performances and documentaries at www.digitice.org.

The International Contemporary Ensemble’s performances and commissioning activities during the 2023-24 concert season are made possible by the generous support of the Ensemble’s board, many individuals, as well as the Mellon Foundation, Howard Gilman Foundation, Jerome Foundation, Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Aaron Copland Fund for Music Inc., Mid Atlantic Arts Foundation, Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts, The Cheswatyr Foundation, Amphion Foundation, The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, New Music USA’s Organizational Development Fund, Alice M. Ditson Fund of Columbia University, BMI Foundation, as well as public funds from the National Endowment for the Arts, New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, the New York State Council for the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature, the Illinois Arts Council Agency, and the Shuttered Venue Operators Grant (SVOG) from the U.S. Small Business Administration. The International Contemporary Ensemble was the Ensemble in Residence of the Nokia Bell Labs Experiments in Art and Technology from 2018-2021. Yamaha Artist Services New York is the exclusive piano provider for the International Contemporary Ensemble.

http://iceorg.org"Abandoned Time offers us another chance to hear modern-guitar polymath Dan Lippel, this time backed by the stellar International Contemporary Ensemble. Performing works by Dai Fujikura, Mario Davidvosky, Kaija Saariaho, Du Yun, and Magnus Lindberg, Lippel and ICE put their hearts into this project, delivering expressive, detailed, and precise interpretations. Standouts on the disc include Davidovsky's Festino for guitar, viola, cello, and bass, a playful piece full of rhythmic counterpoint and percussive guitar writing and string writing, and Saariaho's Adjo, a timbral tour de force featuring the exquisite soprano Tony Arnold.

Pieces like these remind us that the guitar can still function as an expressive centerpiece in contemporary composition. And while this release is by no means "easy listening," those willing to give this cd multiple listens will surely reap the benefits."

—Ian Antonio, Guitar Review, Summer 2009

"Visceral. Muscular. Sensual. Urgent. The language of contemporary music is physical..", so start the liner notes to this CD... and it's totally true in this recording. I'm sure there are those who dislike the disc already, so that's fine, you can stop reading now. If you are still with me, and you have the taste for extremely complex contemporary writing, writing with an almost old-fashioned unashamed atonality that at times does its best to screech the house down... then buy this recording. Lippel is present as the common element to all the pieces, and as a featured instrument rather than a listen-to-me mostly concerto soloist. The piece by Fujikura in fact has him playing an electric guitar, while in the Yun he seems to walk on from off stage playing a pipa or something. At all times all the players giver a tremendous account of these works, perhaps partly because they have had the chance to perform them live many times. Recommended at the highest level to those into this repertoire, or wanting to work in this field, or just to scare the hell out of the neighbors."

—Stephen Kenyon, Classical Guitar, May 2009

"The title track on Dan Lippel’s new CD with the International Contemporary Ensemble, Abandoned Time (New Focus), is scored for chamber group—strings, piano, flute, clarinet—so it’s a bit of a shock when his slithering, distorted electric guitar makes its first entrance. Written by young Japanese composer Dai Fujikura, the piece is packed with collar-grabbing stop-start transitions and dissonant strings that deliver choppy unison parts and ominous long tones, but Lippel’s guitar presides over the proceedings whether it’s screaming atop the din or weaving delicately through it. Also a longtime member of the post-rock band Mice Parade, he tackles a strictly modern repertoire on Abandoned Time, backed with sensitivity and verve by members of ICE, a partly local collective that’s emerged as one of the country’s boldest advocates of new music. Lippel plays acoustic guitar on most of the other compositions—by Mario Davidovsky, Kaija Saariaho, Du Yun, and Magnus Lindberg—and they’re just as demanding, filled with jagged lines, blistering rhythms, and explosions of energy."

—Peter Margasak, Chicago Reader, November 17, 2008

"International Contemporary Ensemble, which was founded in 2001, consists of over thirty musicians, but their performances generally draw on only a handful at a time; this recording features a dozen players, but most of the works are trios or quartets for unconventional combinations of instruments and voice. The unifying element in the repertoire on this CD is its unapologetic modernism -- this is music with a spiky, sinewy physicality that makes no concession to easy accessibility, and there is a good mix of pieces by established and emerging composers. Abandoned Time, by Dai Fujikura, includes almost the whole ensemble, and is essentially a small concerto for electric guitar, played here by Daniel Lippel. Its language may be modernist, but it's not the academic modernism of the late twentieth century; the piece is strongly flavored with a loose-limbed energy and grittiness that's reminiscent of Bang on a Can. Kaija Saariaho's Adjö, for voice, flute, and guitar requires the singer and instrumentalists to use a variety of extended techniques, and is notable for the sense of frantic disjunction that it creates with instruments that are most often used for their lyrical quality. Vicissitudes No. 1, by Du Yun, which includes both Western and traditional Chinese instruments, is characterized by frenzied anxiety, but has an expanse of serene equipoise at its center. The ensemble plays with exquisite precision, understanding, and fierce energy and engagement -- this is a group to watch out for. The sound is exceptionally clear, crisp, and well-defined."

—Stephen Eddins, All Music Guide 2009

"The performances of the International Contemporary Ensemble are staggeringly cool. Dai Fujikura's Abandoned Time is a post-rock soundtrack set to the horror movie of the 20th century. Electric guitar, tube amp, the familiar sound of haunting vibraphone chords, and sharp string eruptions inject a physicality into the work. In the same vein, Vicissitudes no. 1 by Du Yun is urgent, yet torn in identity. At first the saxophones rule the ensemble through free jazz, then a steel guitar centers the atmosphere before the percussion finally prevails. Mario Davidovsky's Festino is a playground for string trio members who have always wanted to imitate guitars with their instruments. Most of the piece is light, though somber in mood, with the real guitar leading the ensemble. The final work on the program is Magnus Lindberg's Linea d'ombra. The clarinet and flute are the early leaders, making their presence known with pointed articulations and light leaps and runs. The pitched percussion and guitar often act like an opposing duo. Breathy sounds and breathing are used in the piece's conclusion, and extended flute techniques and multiphonics from the clarinet appear in tasteful locations."

—Lamper, American Record Guide, January/February 2009