John Aylward's chamber opera Oblivion tackles questions of memory, self-knowledge, and meaning through its rich, colorful score for four voices, viola, cello, double bass, electric guitar, and electronics. Inspired by the writings of Dante and Joseph Campbell, Aylward grapples with self-inquiry, crafting a fantastical tale that prompts timeless existential conundrums that we all face.

| # | Audio | Title/Composer(s) | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time | 64:35 | ||

Oblivion |

|||

| 01 | I. Prologue | I. Prologue | 4:13 |

| 02 | II. Scene 1 | II. Scene 1 | 6:29 |

| 03 | III. Scene 2 | III. Scene 2 | 8:21 |

| 04 | IV. Scene 3 | IV. Scene 3 | 6:05 |

| 05 | V. Scene 4 | V. Scene 4 | 12:48 |

| 06 | VI. Scene 5 & Interlude | VI. Scene 5 & Interlude | 12:19 |

| 07 | VII. Scene 6 | VII. Scene 6 | 14:20 |

John Aylward’s chamber opera Oblivion grapples with issues of remembering, destiny, and self-knowledge. His score for four voices, viola, cello, double bass, electric guitar and electronics is beguiling and mysterious, accompanying the opera’s protagonists through a labyrinthine journey loosely based on Dante’s Purgatory but taking cues from Joseph Campbell and a range of other historic and modern philosophers and theologians. Ultimately, Aylward has created a piece that teems with existential wonder and pathos.

Musically, Aylward’s language is grounded in a harmonic palette indebted to Olivier Messiaen and Henri Dutilleux, with an instrumentation that skews towards the low register so as to entertain possibilities of unique spectral timbres. There is a strong presence of certain versatile intervallic constructions in the chordal language, particularly all-interval tetrachords that often hint at octatonic collections that Aylward often filters into whole-tone fragments. Aylward uses large scale polyrhythm and rhythmic displacements, indicative of Christophe Bertrand’s orchestrations, to expand sections, creating a kind of spectral undulation of a single harmony, as heard in the opening of Scene 1. Aylward uses electronics primarily atmospherically, fashioning ambient spaces within which action of the voices and ensemble unfolds.

The Prologue opens with exactly such material: a foreboding windscape out of which the ensemble comes to life with anxious starts. Ponticello gestures and harmonics in the strings along with a chorus-effected electric guitar set the haunting scene beautifully. The first scene finds the first of the two protagonists, the First Wanderer (baritone Tyler Boque), coming upon the lair of an enigmatic Hunter after wandering in the wilderness. The Wanderer’s disorientation is captured in the halting vocal part and the juxtaposed material in the ensemble. A bound man lurks in the corner, characterized by the Hunter as dangerous. Scene 2 introduces the Second Wanderer (soprano Nina Guo) who is also disoriented and unsure of how she arrived at the Hunter’s lair. Aylward captures the characters’ befuddlement by virtuosically intertwining spoken and sung texts with angular figures in the instruments.

Read MoreScene 3 finds the two Wanderers processing all they’ve taken in from such an otherworldly landscape. Their dialogue unfolds over woozy glissandi and delicate trills. Throughout the piece, Aylward sets these philosophical ruminations off by stripping down the instrumentation. We hear a recitative-like duo between soprano and electric guitar in the middle of this scene, or, later, a duet between viola and baritone. Through Scene 4, Aylward continues to deftly use the ensemble to press the momentum forward as the Bound Man transforms into a King and promises the Wanderers salvation if they follow him and vanquish the Hunter. The King’s arias here are dramatically underscored with virtuosic contrabass writing that is rarely heard in operatic settings.

The action in the plot pauses in Scene 5 as the Wanderers come to terms with their plight, and observe how the journey has transformed their understanding of themselves and each other. Aylward paints their evolving comprehension with pensive harmonies and timbres that evoke an intimate and personal melancholy. The final scene unleashes much of the previous scenes’ pent-up energy with emphatic tutti accents as the Wanderers and the King confront the Hunter. Aylward’s setting of the rhetorical sparring, as the characters accuse each other of deception, has a classic operatic feel to the vocal counterpoint. These climactic four-way interactions are set with dense orchestrations of swooping glissandi, chordal swells, and technically masterful ensemble singing.

As the piece ends and the fog lifts, we are left to wonder if the King has in fact duped the First Wanderer. The closing material in the ensemble has an ethereal and disembodied ambience, as if the musical figures themselves are circles in Purgatory. Aylward’s hollow Lynchian windscape from the opening returns, a dark echo of a world perhaps bereft. How can we learn the truth of our lives? How do we distinguish reality from illusion, or worse, deception, especially in an era of untruth? What, if any, meaning can we take away from our time on the earth if our understanding is clouded by circumstance and obfuscation? Aylward’s opera elegantly raises these questions and ruminates on the enigma, as they are, for the honest among us, unanswerable.

– Dan Lippel

Recorded at the Bombyx Center for Arts and Equity, Florence, Massachusetts, June 25th–30th, 2022

Produced by John Aylward

Joel Gordon, recording engineer

Peter Atkinson, recording assistant

Edited, mixed and mastered by Joel Gordon and John Aylward

Design, layout & typography: Marc Wolf, marcjwolf.com

Cover Image: Composite of stills from the August 2022 film production: Top image: Stage set; Bottom image: Nina Guo

Soprano Nina Guo is interested in the sounds of recent and ongoing times, and her performance practice includes interpreting notated music, improvising, and collaborating on interdisciplinary projects. As a contemporary music specialist, she has performed with groups like Ensemble Modern, Decoder Ensemble, and ECCE, and has been featured at festivals like Acht Brücken (Köln), Passion:SPIEL at the Deutsches National Theater (Weimar), and Music in Time at Spoleto Festival (Charleston). Nina’s personal projects include several duo collaborations. Departure Duo, a contemporary music soprano+double bass duo with Edward Kass, released its debut album 'Immensity Of' on New Focus Recordings in 2022. With artist Leonie Brandner, Nina made MOSSOPERA, a long duration installation opera for two voices, dictaphones, and ceramic resonators. In the last years, radio has become an important part of her practice, and her live comedy variety show, The Entertainment, is hosted by Cashmere Radio (Berlin).

Lukas Papenfusscline is a singer and performance-maker living in New York City. They specialize in medieval and contemporary song, working exclusively in collaborative environments and through the lens of queerness. A sought-after vocalist for concert, opera, and theatre, Lukas also leads a band, mammifères, that adapts music of the past through ethnic chaos. "Olema," the band's first album, explored American folk and "Bestiary" (upcoming) dives into medieval music. Lukas’ extensive performance experience has brought them all around the world to legendary venues like the Getty Villa Museum, NYPL’s Jefferson Market Library, La MaMa, Théâtre du Châtelet, and the Hirshhorn Museum.

Tyler Bouque is a baritone and composer born and raised in Troy, Michigan. As a performer, Bouque specializes in contemporary music, with a repertoire largely comprised of works from the last century. He is a firm believer in directly engaging with composers to realize their compositional visions, and among his repertoire, which spans solo, chamber, and operatic works, are several pieces specifically written for him. As a composer, his interests lie in the intersection of literature, linguistics, theater, and music . Bouque’s writing often turns to the “expression beyond language” — that which lies beneath text — as a primary informant. He is currently working on a musiktheater cycle after Dante’s Inferno. Also active in music research, Bouque is currently working on a book detailing the history of opera post-1925.

https://tybouque.comBaritone Cailin Marcel Manson, a Philadelphia native, has enjoyed an international career as an operatic/concert solo- ist, conductor, and master teacher with many organizations, including the Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart, SWR Sinfonieorchester, Taipei Philharmonic, Bayerische Staatsoper- Münchner Opernfestspiele, Choral Arts Society of Philadelphia, Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, Teatro La Fenice, Teatro San Carlo, Konservatorium Oslo, and the Conservatoire de Luxembourg. He has also been a guest cantor and soloist at some of the world’s most famous churches and cathedrals, including Notre Dame, Sacré-Coeur, and La Madeleine in Paris, San Marco in Venice, Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, San Salvatore in Montalcino, Santa Maria Maggiore and San Giovanni in Laterano in Rome, Thomaskirche and Nikolaikirche in Leipzig, and Wieskirche in Steingaden. Cailin has built a sterling reputation over an extensive 20-year career, encompassing both baritone and tenor repertoire, for his exceptional musicianship, keen dramatic instincts, and vocal flexibility. Critics have praised his performances roles as "arresting" and "revelatory," making consistent note of his "ringing projection," "commanding presence," and "ability to bring the internal drama of the music to life."

Laura Williamson is a string player in the Boston area. She received a masters degree from New England Conservatory following her undergraduate studies at Vanderbilt University. Her most influential teachers include Aaron Janse, Kathryn Plummer, and Marcus Thompson. Laura can be heard performing around Boston with the Boston Festival Orchestra, Eureka Ensemble, Cape Ann Symphony, and others. Laura teaches private lessons in violin and viola as well as violin ensemble classes and Suzuki Early Childhood Education at New England Conservatory Preparatory School.

Cellist Issei Herr is committed to a diverse array of music both old and new. A compelling soloist and a dedicated collaborator, Issei performs a scope of repertoire that ranges from the music of Bach, Babbitt, and Berio to Schubert, Schoenberg, and Stravinsky. Issei is a fierce advocate of the music of our time, working closely with living composers to develop emerging repertoire and presenting new works in the context of innovative concert programs.

Greg Chudzik is an active performer across numerous genres on the double bass and electric bass. Currently, he can be seen performing regularly with several new music groups, including Signal Ensemble, Wet Ink Ensemble, and Talea Ensemble. Greg is also a member of several bands, including Empyrean Atlas, Bing and Ruth, and The Briars of North America. He has worked with numerous influential figures in contemporary music, including Steve Coleman, Steve Reich, Brian Ferneyhough, Pierre Boulez, George Benjamin, Helmut Lachenmann, Charles Wuorinen, Alex Mincek and Tristan Perich. Greg’s recording credits include playing on the Grammy-nominated “Barcelonaza” by Jorge Leiderman, “Pulse / Quartet” by Steve Reich on Nonesuch records, “Morphogenesis” and "Synovial Joints" by Steve Coleman on Pi Recordings, “No Home of the Mind” and "Tomorrow Was the Golden Age" by Bing and Ruth on RVNG records, the album “Americans” by Scott Johnson (Tzadik records), multiple recordings with Signal Ensemble on New Amsterdam and Mode Records, the album “Grown Unknown” by Lia Ices (Secretly Canadian records), the album "Inner Circle" by Empyrean Atlas, and the album “High Violet” by The National on 4AD records. Greg's debut album "Solo Works, Vol. 1" was released in July of 2015 and features original pieces of music written for bass guitar and electronics.

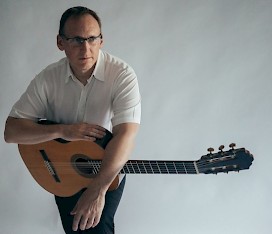

http://www.gregchudzik.com Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

John Aylward has been described by the Boston Globe as "A composer of wide intellectual curiosity" who summons "textures of efficient richness, delicate and deep all at once." His music is influenced by a range of modern and ancient literature and deeply affected by time spent in the deserts of Arizona and New Mexico. These streams of influence have led to a music that considers ancestral concepts of time, appropriations of indigenous cultures into surrealism, impressionism and post-modernism, and the connections between creative mythologies across civilizations.

John Aylward has been described by the Boston Globe as "A composer of wide intellectual curiosity" who summons "textures of efficient richness, delicate and deep all at once." His music is influenced by a range of modern and ancient literature and deeply affected by time spent in the deserts of Arizona and New Mexico. These streams of influence have led to a music that considers ancestral concepts of time, appropriations of indigenous cultures into surrealism, impressionism and post-modernism, and the connections between creative mythologies across civilizations.

Aylward's work has been performed internationally by a range of ensembles and soloists, and his own ensemble, Ecce, has served as a laboratory for his larger projects to take shape. Both as a pianist and as a director of the Etchings Festival, Aylward has supported new music of all kinds through commissions and performances.

Awards and fellowships include those from the American Academy of Arts and Letters (the Walter Hinrichsen Award and a Goddard Lieberson Fellowship) the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute at Harvard University, the Koussevitzky Commission from the Library of Congress, the Fromm Music Foundation, the Fulbright Foundation, the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, the MacDowell Colony, the Atlantic Center for the Arts, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, First Prize from the International Society for Contemporary Music, and many others.

Aylward holds composition degrees (MFA, PhD) from Brandeis University and a degree in piano performance (BM) from the University of Arizona. John lives in Northampton, Massachusetts, with his wife Kate, and teaches music composition at Clark University.

Born in China, Tianyi Wang is an award-winning composer, conductor, and pianist, whose music vocabulary is diverse and much inspired by subjects beyond music. Tianyi’s repertoire spans over solo, chamber, choral, orchestral, electroacoustic, as well as film scoring. His works have been performed by en- sembles and festivals around the globe, including Darmstädter Ferienkurse, Boston Modern Orchestra Project, impuls Festival, Festival Mixtur, Meitar Ensemble, ensemble blank, iNEnesemble, Audiograft Festival, Ashmolean Museum, Ensemble MISE-EN, and many others. He is the winner of 2020 MUSIQA Emerging Composer Commission Competition, 2018-19 New England Conservatory of Music Honors Composition Com- petition, 2018 BMOP/NEC Composition Competition, 2017 Longy Orchestral Composition Competition, and 2016 Sanya International Choral Festival. He is also a recipient of China National Arts Fund in 2017. Tianyi’s music has been released by Navona, Ablaze, and Petrichor Records.

Stratis Minakakis is a composer and conductor whose work engages memory, cultural identity, and art as social testimony; it also explores the rich possibilities engendered by the interaction between arts and sciences. As a composer, he has received commissions from and collaborated with leading performers and ensembles, such as the Grammy award-wining Crossing Choir, Prism Saxophone Quartet, and Partch Ensemble. Other notable partners include saxophonist Don-Paul Kahl, Ensemble du Bout du Monde, pianist Jihye Chang, soprano Nina Dante, flutist Dalia Chin, and cellist Annie Jacobs-Perkins. As a conductor, he has directed numerous ensembles in contemporary repertory, including world premieres by Ken Ueno, Mathew Rosenbaum and John Aylward, and the North American premiere of Sciarrino’s Quaderno di Strada. A highly sought-after studio instructor, he has taught in numerous institutions and festivals in the United States and Europe. Deeply committed to music pedagogy, he was awarded the Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching at the University of Pennsylvania and the Louis Krasner Award for Teaching Excellence at New England Conservatory. Stratis Minakakis studied composition, theory, and piano performance at the University of Pennsylvania, New England Conservatory, Princeton University, and Athenaeum Conservatory. He currently teaches Composition and Music Theory at New England Conservatory.

Two wanderers, a man and a woman, move through an otherworldly place reminiscent of Dante’s purgatory where they encounter two strange, archetypal figures – a hunter and a bound man who turns out to be a king. This is the basic storyline of John Aylward’s Oblivion, a one-act opera whose characters and scenario seem to have come from one of those obscurely symbolic dreams one sometimes has just before waking up.

In contrast to grand opera’s lush orchestration, Oblivion’s music is scored for an austere quartet of viola (Laura Williamson), cello (Issei Herr), double bass (Greg Chudzik), and electric guitar (Daniel Lippel). From this minimal ensemble Aylward derives a maximum of dramatic tension, often playing the strings’ long, dissonant tones against the guitar’s staccato broken chords. Both the size and the makeup of the ensemble lend the music a bracing clarity that brings the voices into focus. The opera’s characters, sung by soprano Nina Guo, tenor Lukas Papenfusscline, and baritones Tyler Boque and Cailin Marcel Manson, are sharply individuated. They, supported by the instrumental quartet’s precisely played accompaniment, bring this unsettling work vividly to life.

— Daniel Barbiero, 9.26.2023

Is it possible to have a genuine opera in which everybody is dead in the opening scene? Even if the characters need a scene or two to figure out that they’re in some sort of ‘next world’? John Aylward’s one-act Oblivion, obviously, is alt-opera, a 65-minute through-composed work that seems created more for the recording studio than for the stage in its atmospheric netherworld: it drifts towards No Exit, Waiting for Godot and Dante’s Purgatorio while recalling Pelléas et Mélisande with a magic-fountain plot point allowing characters to gain back memory of the lives they lost.

Not only do a man and a woman wake up in the afterlife, slowly remembering that one might have killed the other, but they don’t know if they should believe the two opposing ruling forces – a hunter and a self-proclaimed king – who give opposing accounts of the current existential realities. ‘A central question is what might be gained from remembering’, writes Aylward in the booklet notes. ‘Will remembrance bring them knowledge and perspective, or pain and regret?’

Whether or not such dilemmas are important to the listener, the composer-authored libretto carries the spare score that accommodates relatively narrow-range, non-operatic voices and implies more than it says. Mostly devoid of operatic histrionics, the vocal writing ranges from spasmodic exclamations (something like György Kurtág’s Endgame) to straightforward, conversational word-settings in the unostentatious spirit of Jonathan Dove. The music sometimes coalesces into philosophical mediations for the male First Wanderer (Tyler Boque), while vocal lines for Second Wanderer take on a fleeting lyricism that shows Nina Guo to have a lustrous, articulate soprano in an opera that rarely asks for such fine singing.

The chamber-ensemble instrumentation with electronic augmentation is spare but deployed with implied spaciousness. Racing and skittering viola- and cello-writing is anchored by drone effects as well as electronic white (or off-white) noise. Disembodied collages of sound are heard in distant proximity from each other. Serpentine bass glissandos and well-chosen electric guitar effects invade and retreat. Where the music sits on the tonal v atonal spectrum is part of the opera’s ambiguity – and keeps the ear moving forwards despite a lack of traditional harmonic momentum.

The piece holds one’s attention but has a significant component that’s yet to come: a film version that, as of this writing, is in post-production and heading for the film festival circuit. The scenes that I’ve seen present the afterlife as a visually grainy version of real life, with claustrophobic close-ups that elucidate the opera’s power dynamics – much needed in a piece whose characters lack specific names. No doubt the film will also suggest why nobody seems to find their way out of this purgatory. Aylward is an imaginative, resourceful talent who may be ready to consolidate his previous experimentation into something that could communicate beyond contemporary music circles.

— David Patrick Stearns, 10.05.2023

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/discover-music-with-anearful/id1588981051?i=1000629909693

— Jeremy Shatan, 10.05.2023

Two memory-stricken wanderers enter a shelter inhabited by a hunter and a gibberish-spouting bound man. At night and unseen by the hunter, the man and woman free the captive and, happening upon a fountain capable of restoring memory, determine that the bound man is, in fact, a king and the wanderers dead and in purgatory. Suffice it to say, the libretto John Aylward wrote for his opera, packed as the narrative is with mystery and revelations, is as gripping as the score. Works by the Northampton, Massachusetts-based composer have been performed by a number of ensembles, including his own Ecce, but in keeping with the intimate, even hermetic character of Oblivion, only five instrumentalists accompany the four vocalists on the sixty-four-minute recording. Credited with electronics, Aylward is one of the performers, violist Laura Williamson, cellist Issei Herr, contrabassist Greg Chudzik, and electric guitarist Daniel Lippel the others. Soprano Nina Guo (second wanderer), baritone Tyler Boque (first wanderer), tenor Lukas Papenfusscline (bound man), and baritone Cailin Manson (hunter) are the singers, with conducting by Stratis Minakakis and Tianyi Wang assisting with electronic sound design.

While text accompanying the release indicates that Aylward's musical language is indebted to Messiaen and Dutilleux, a third name could be added to theirs, specifically John Casken for his 1989 work Golem. Like Oblivion, the English composer's creation is a chamber opera featuring modest vocal and instrumental forces and incorporating electronic sound design. It's more the cryptic tone of the work, however, that identifies it as a complementary work to Aylward's. The libretto of Oblivion is riveting too, with exchanges between the wanderers calling to mind similar back-and-forth between Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot. Other literary references for Oblivioninclude writings by Dante and Joseph Campbell.

The wanderers are desperate to know where they've come from and the nature of the realm they've entered, such things emblematic of existential themes having to do with memory, identity, and destiny. The opera proper begins after a haunting “Prologue” with the male wanderer entering the lair of the enigmatic hunter and encountering the bound man. The visitor's condition is revealed early (“I can't remember anything of myself. I wandered for what seemed an eternity”) as he speaks with the hunter, the captive interjecting with seemingly nonsensical babble. Soon after, the female wanderer arrives, she as disoriented and mystified as to how she came to the hunter's lair, and their shared perplexity is conveyed in flurries of overlapping speech. If Beckett's protagonists are waiting for Godot, Aylward's are hoping to achieve some semblance of clarity.

Gradually they decide to leave the lair in the hope of determining who they are and how they've come to be there (the first wanderer: “Perhaps there is a reason we found this place, and each other. There must be a reason why”). Taking the bound man with them, they flee into a dreamlike passageway and come to a fountain, with contrabass playing mirroring the agitation of the bound man as his memory returns and his status as king recollected. Drinking from the fountain too, the first wanderer realizes that he and the second were lovers and begins to think that she perhaps killed him. The now-king argues that they must vanquish the hunter in order to reclaim their world, and in words reminiscent of Kafka's Before the Law, states, “He guards the doorway to ascension. He lets no one pass, turning them to the wild.” The final scene involves a climactic confrontation between the wanderers, king, and hunter, with accusations flung back and forth and vocal counterpoint reflecting the violence of the discourse. Though determining whose words can be relied upon proves challenging, the first wanderer nevertheless kills the hunter, an act that, in the king's eyes, fulfills the wanderer's purpose. A late twist invites a reconsideration of the story and leaves us with as many questions as answers about self-understanding and personal destiny.

Stylistically, Aylward eschews conventional opera practice for a score that's text-directed. No arias are present; instead, the four singers speak as much as sing, with the instrumental material taking its cues from the vocal design. Strings and guitar function as extensions of the singing, with instrumental gestures and commentaries as agitated as expressions by the characters. Aylward's use of electronics is tastefully handled, with the elements used to build atmosphere, in the foreboding “Prologue” especially, and create an overriding sense of disturbance and disorientation. The different shadings of the relationships between the characters are conveyed vividly through vocal performances that are deeply attuned to the libretto and sensitive to each other. The same could be said of the relationship between the singers and the instrumentalists when the latter complement so splendidly the emotional tone of the characters' expressions. Oblivion is a distinctive work, obviously; even better, the modest number of vocalists and musicians needed to perform it make it an all the more feasible piece for smaller opera companies to present.

— Ron Schepper, 11.07.2023

Oblivion is an opera in one act with music and libretto by the US-based composer John Aylward, recently released by New Focus Recordings in a performance featuring tenor Lukas Papenfusscline, baritone Cailin Marcel Manson, baritone Tyler Boque, soprano Nina Guo, violist Laura Williamson, cellist Issei Herr, contrabassist Greg Chudzik and guitarist Daniel Lippel. In addition, the performance - which was recorded in June 2022 at the Bombyx Center for Arts and Equity in Florence, Massachusetts - features Aylward on electronics, Stratis Minakakis as music director and conductor and Tianyi Wang as electronic sound design assistant. The sixty-four-minute album is available in CD and digital format and includes a substantial booklet featuring a composer's note on the opera, a synopsis of the scenes, production photographs and the entire libretto.

To paraphrase Aylward's synopsis from the liner notes, Oblivion reimagines the Purgatorio of Dante Alighieri in the form of a modern dramatic archetype with influences from the writings of Joseph Campbell. Over the course of an instrumental prologue and six scenes, the opera tells the story of two recently deceased souls who awaken to find themselves as wanderers (Boque and Guo) in a mysterious room, having no memory of their lives on earth. Here they meet a Bound Man (Papenfusscline) whom the Hunter (Manson), who rules the land, declares to be dangerous and has tied up. Knowing only these facts, the wanderers must then choose whom to believe and what to do next.

The opera opens with about one minute of Aylward's electronics playing a quiet sound evocative of distant wind. This is followed by the entrance of freely atonal string music gradually settling into a late-Romantic-style sound world of continually shifting diatonic centers. The strings and electronics then subside and the electric guitar emerges briefly before the four-minute prologue continues attacca into the first scene, in which the First Wanderer, Hunter and Bound Man are introduced.

From scene one on through the rest of the opera, the vocal music is essentially all recitative with distinctive rhythmic patterns differentiating the personalities of the characters. For instance, the Bound Man is always heard singing more staccato than the others. Meanwhile, the textural momentum of the instrumental music is continuously shifting. In scene one, this includes moments of tremolo and pizzicato in the strings and long spacious notes in the guitar. At the same time, the harmonic palette freely explores chromatic and whole-tone sonorities, with tritones seeming to take on a role of structural emphasis.

Scene two sees a continuation of this sound world first established in scene one, namely the constant fluctuation of harmony and the use of dynamics and rhythmic energy to embody the action of the plot. This is music which - like the wanderers themselves - seems to exist in, and for, the moment, without an obvious orientation toward either origin or destiny. This scene focuses on the introduction of the Second Wanderer into the story and the relationship between the two wanderers in the afterlife. By now it is apparent that it is primarily the emotion of the dialogue and plot that dictates the form of the music and its organization, mostly through the aforementioned scheme of dynamics and rhythmic energy.

The harmonies in scene three, however, gradually emerge as an additional parameter of expressive emphasis, converging into a kind of tonal resolution at the end of that scene before the music fades into silence. This rare pause between scenes seems to underscore the moment as significant in the opera, since the rest of the opera's scene transitions are attacca. For reference, the action at this dramatic midpoint sees the wanderers becoming aware of the Bound Man's pleas to be freed and eventually untying him.

In scene four, the bound man's voice becomes more like that of the wanderers - less of a hurried staccato and more of a slow legato - as he reveals himself to actually be the king of the realm, having been overthrown and held prisoner by the hunter. The instruments close out the scene with low registers in the strings and gentle, slow textures transitioning attacca into the next scene.

Scene five sees the wanders disagreeing about whether or not to expel the Hunter and restore power over the realm to the King (formerly known as the Bound Man). The music continues with the sonic premises previously established, ending with a five-minute instrumental interlude. Here, the music settles into a strikingly slow pace and quiet dynamic characterized by soft, rain-like pizzicatopassages on strings over sustained bass tones. The climax of the interlude features what appears to be a harmonic evocation of the natural overtone series, melding into a subtle tremolo sonority sustained on guitar. This leads attacca into the final scene.

In the sixth and final scene, the King promises the wanderers that he will grant them passage out of purgatory into paradise if they expel the Hunter, thus restoring his kingdom. Musically, the voices of the Hunter and the King reach their registral heights before both fall into silence. The First Wanderer expels the Hunter against the Second Wanderer's wishes and then sings in increasingly lower registers until he reaches the bottom of his vocal range. As the instrumental music concludes the scene, the electronic wind sound returns from the very beginning of the opera, adding a sense of symmetry to the whole arc of the story. While I will not spoil the conclusion of the plot, I will say that its musical treatment seems to underscore the sense that a kind of cycle has been completed over the course of the whole opera.

As an opera, Oblivion draws upon a sophisticated and fluid contemporary sonic palette to reflect both the drama and spirit of the libretto in every moment of the performance. Being so well integrated as a fusion of music and text, it seems most appropriate to assess the opera as a unified whole on its own terms. John Aylward arguably poses far more questions through the story than he answers, and these questions have profound implications in matters of deterministic causality, free will and personal responsibility and legacy. Who is more trustworthy: the Hunter, or the Bound Man? Did the wanderers make the right choice in setting the Bound Man free? Did the First Wanderer make the right choice in expelling the Hunter? Is there justice in this vision of purgatory? This is an enigmatic and philosophically challenging work of art - one which revisits some of humanity's oldest questions through some of opera's newest technical and aesthetic developments.

— John Dante Prevedini, 11.13.2023

Opera is an iffy enterprise in the domain of New Music, where a composer’s idiom typically needs specialized singers who can encompass extreme vocal gestures. Achieving that, there’s the question of how receptive an audience will be. John Aylward’s one-act, one-hour chamber opera, Oblivion, is quite accommodating on the second front. Audiences who have absorbed Lulu, or even Wozzeck, won’t be taxed—quite the opposite. The vocal lines generally exclude the wide leaps and stratospheric extremes of, for example, Thomas Adès’s The Tempest. Story and music match with appealing accessibility.

Aylward, who performs the electronics in the instrumental ensemble, wrote his own libretto, a modern allegory. Its ground plan is succinctly given in his composer’s note: “The protagonists in Oblivion are two Wanderers, loosely related to the eponymous first-person narrator of Dante’s Purgatory, the second part of his Divine Comedy. As in that famous depiction of the afterlife, my Wanderers confront allegorical figures who challenge them to more deeply understand themselves.”

That tells you enough to anticipate otherworldly atmospherics and a tendency toward low instrumental registers. The program notes tell us that Oblivion’s “language is grounded in a harmonic palette indebted to Olivier Messiaen and Henri Dutilleux.” (I won’t pretend to understand what is meant by “all-interval tetrachords that often hint at octatonic collections.”) The singers enunciate with perfect intelligibility, encompassing several vocal modes: singing, speaking, parlando, and some modernist vocal gestures like a kind of stuttering. The pace is often conversational, proceeding in single vocal lines, and there is transparent clarity in the scoring for four voices (soprano, tenor, and two baritones) and a quintet of viola, cello, double bass, electric guitar, and electronics.

The core of the story is existential searching in a blank Beckett-like space. The two young Wanderers, very ably performed by soprano Nina Guo and baritone Tyler Boque, are faced with a contemporary version of Dante’s purgation of the soul, in this case updated to self-knowledge. The Wanderers enter separately from the same wilderness (in the vein of Dante’s dark wood) and without memory. There are not-so-hidden literary references, such as the imitation of Waiting for Godot when the two Wanderers set off with the chained Bound Man in tow. When the Bound Man drinks from a fountain, his memory is restored, and he realizes that he is a king, a reversal of the waters of the River Lethe in Greek mythology that erase memory.

What one fears when composers write their own librettos is an embarrassing amateurishness, but Aylward does respectably, and his sincerity, drawing from his own religious upbringing as a Catholic, grounds the mixture of mythology and psychotherapy. The purgatorial element is revealed by the restorative powers of the fountain. The two Wanderers, lovers in life, have died, and the space they are wandering in was seized by the villainous Hunter, who is blocking the way to Heaven.

Without revealing the rest of the plot, its themes are guilt, remembrance, and rapturous awakening. All of this has convincing overtones for a wide, receptive audience, I think. Being oblivious to the possibility of awakening is a fraught spiritual issue that Aylward deals with beautifully. Christian redemption is replaced by awakened awareness. The risk of preachiness is avoided through plot twists and the ambiguity of whether any of these characters are really who they claim to be. Aylward’s musical tapestry keeps pace with every turn of fortune, skillfully underscoring each shifting mood with continuous ingenuity and a shimmering color palette. Every aspect of the performance, vocal and instrumental, is expert, including the electronica, which is atmospheric and never intrusive.

It’s a feature of Aylward’s accomplishment (and a rarity in New Music) that Oblivion tells its own story without an overlay of high concept and technical jargon. Once gripped by the music and libretto, your attention is held throughout, and every character is involving in a direct, human way. I came away much more impressed than I expected. Aylward has created that rarity, an accessible New Music opera with a human connection.

— Huntley Dent, 3.12.2024

This is a new chamber opera in one act, with a libretto by the composer. John Aylward, an associate professor at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, grew up in the Sonoran Desert, on the border of Arizona and Mexico. “My music,” he writes, “processes the impacts of that earlier life, filled with a deep sense of community, rich expressions of converging cultural histories, and the otherworldly landscapes of the desert.”

The opera is set in a “cavernous shelter” where The Hunter has imprisoned The Bound Man. Two Wanderers, both confused as to their whereabouts and their identities, separately enter the shelter in search of food and refuge from a storm. The Hunter provides them with both, but warns them not to speak to The Bound Man, and tells them that they must soon go back into “the wild.” As soon as The Hunter falls asleep, they defy him, and The Bound Man persuades them to release him. The three of them drink from a fountain which, one by one, restores their memory. The Bound Man, now The King, tells them that if they help him to overcome The Hunter, he will free them from this purgatory. By the end of the opera, the characters have changed places; now the First Wanderer’s reward is to be chained where The King was bound at the opera’s beginning. The Hunter then enters, presumably now as a new Wanderer. The story is influenced by Dante’s Purgatory, Joseph Campbell’s writings (The Power of Myth), and Aylward’s Roman Catholic upbringing. Aylward writes, “Ultimately, the opera asks if we can escape ourselves through forgetting and whether redemption, that highest of Catholic concepts, is worth seeking after all.”

Clearly, this is a lot of baggage for a one-act opera. Then one reads that the composer’s language “is grounded in a harmonic palette indebted to Olivier Messiaen and Henri Dutilleux.” I doubt that most listeners will pick up on that; I didn’t, anyway. We also read, “There is a strong presence of certain versatile intervallic constructions in the chordal language, particularly all-interval tetrachords that often hint at octatonic collections that Aylward often filters into whole-tone fragments.” Again, this is good to know, but I am wondering how many listeners will be aware of this, and of the relevance that it has to their experience of Oblivion.

Aylward’s vocal writing tends toward the declamatory, although there are lyrical sections too, particularly as the characters begin to uncover their identities. Don’t expect an aria or a vocal quartet, though. The writing reminds me, sometimes, of Robert Ashley, particularly his Improvement, an opera that I unreservedly love. Improvement, while it is anything but straightforward, has an impish sense of humor, a quality lacking in Oblivion, which is deadly earnest. One is drawn more to the words than to the music, and sometimes more to the instrumental writing than to the voices. That said, Aylward is quite skillful at giving a different musical profile to each of his characters. I’m intrigued by Oblivion, and I don’t doubt that there is more to the music, and to its meanings, than what is apparent after two or three hearings. Like any opera, it would be better to see it than merely to hear it, so I am going to stay on the fence, at least for now. There are several photos in the booklet that suggest either a live production or a video, but there is nothing to indicate that this opera has been performed, except in the studio during the making of this CD.

The singers are outstanding both as singers and as vocal actors, particularly Lukas Papenfusscline, whose nervously stammering Bound Man sets the scene. Aylward was an active participant in the making of this recording, and I hope he got what he was looking for. I have no reason to think that he didn’t.

— Raymond Tuttle, 3.12.2024

The doctrine of Purgatory, largely based on a few vague lines of apocryphal scripture, is an oft-misunderstood facet of Catholicism. The catechism never explicitly refers to it as a place. Rather, it’s described as a process of purification for dead believers who must be fully cleansed before entering heaven. Of course, this hasn’t kept artists and theologians from imagining purgatory as a physical space and speculating on how expiation is attained there. Dante conceived of it as a terraced mountain scaled by penitent souls. At its peak flows the River Lethe, which wipes their memories clean, followed by the Eunoe, which recovers only good memories.

John Aylward’s 2022 chamber opera “Oblivion,” released on New Focus Recordings, presents a vision of purgatory indebted to Dante. Only, the “rules” of Aylward’s afterlife are far less clear-cut than in the “Divine Comedy.” The composer’s self-written libretto opens on a scene redolent of “Die Walküre”: lost in a stormy wilderness, two amnesiac Wanderers—one male, one female—seek shelter in the hovel of a Hunter. Here they also encounter a madman held captive by their churlish host. These two figures offer the Wanderers conflicting routes to redemption. The Hunter contends that salvation is won by enduring the hardships of the wasteland beyond his door. But the madman, claiming to be the King of this realm, instructs them to drink from a memory-restoring fountain and atone for every sin they recall.

The opera is less a manual for the next life than an allegory for the present one. In response to his Catholic upbringing, Aylward examines the usefulness of atonement, even questioning whether it’s truly achievable. “Redemption is an allusion,” female Wanderer concludes. Indeed, at the opera’s outset, the two protagonists exist in a blissfully ignorant freedom, like Adam and Eve. But when the male Wanderer is tempted into tasting the mnemonic water, the knowledge of his prior transgressions only induces further wrongdoing. Rather than asking forgiveness of the female Wanderer, who turns out to have been his wife, he projects his guilt onto those around him—ultimately committing a terrible evil in the name of “justice.”

In this, his second opera, Aylward has crafted a brilliant piece of drama that ranks among the classics of absurdist theater. And like all great works, “Oblivion” continuously divulges new layers of meaning. In the space of an hour, Aylward lays out a vast moral and philosophical labyrinth for the listener to roam. Its complexities and ambiguities are unsolvable, and by the final scene, one gets the sense of being suspended in their own infinite and inescapable limbo.

Aylward’s musical world can only be described as purgatorial. The prologue commences with an electronic evocation of nothingness: a grey, whooshing soundscape like the echo of a cavern. Our four instrumental soloists, led by conductor Stratis Minakakis, gradually materialize out of this abyss. The unusual scoring for double bass, cello, viola, and electric guitar in lieu of violin generates strange, ethereal timbres. Very often, the low strings will float motionlessly on droning Wagnerian or Debussyian harmonies while guitarist Daniel Lippel pendulates tentatively between two pinging pitches.

The accompaniment always seems to linger hesitantly on the verge of something that never quite arrives. As the story unfolds, the players—much like the characters—attempt to break out of their inertia with impotent, endlessly circling gestures that only give the appearance of activity. The score’s central motive is a perpetually zigzagging figure—alternating ascending and descending intervals that expand progressively like a wedge before inevitably returning to the center. Aylward also favors a slowly accelerating trill that fails to resolve. Just as the Wanderers are unable to determine the true path to redemption, these trills simply coalesce as a chord on both notes, hanging with dissonant uncertainty like a question mark.

Contemporary opera has grown far too dialogue-heavy of late. New works tend to devolve into meandering stretches of bland recitative, with few passages of lyrical introspection. While Aylward’s libretto is no less dialogic and could even work as a straight play, he is one of the few living composers who thrives on such texts. His vocal writing is highly reminiscent of the stylized naturalism exhibited in George Benjamin’s operas. Aylward generates authentically conversational rhythms and contours while also endowing every line with inherent musicality and momentum.

More importantly, he pays keen attention to characterization, delineating each of his dramatis personae with a distinct sonic palette. Lukas Papenfusscline’s quivering vibrato perfectly suits the jittery, power-hungry King. The tenor mutters eerie apocalyptic prophecies in flurries of manic thirty-second notes resembling an addict’s delirious ranting. Baritone Cailin Marcel Manson is an ideal foil as the Hunter, his gruff admonitions growled with paternal authority.

As the female Wanderer, it’s clear to see why Nina Guo has served as a muse for Aylward, who has composed for her voice on multiple occasions. The soprano possesses a bright, flitting instrument and applies very little vibrato, lending her a tone of avian delicacy that transcends stylistic classification. She excels in softer passages of near-whispered intimacy, which she delivers as if emerging from a drowsy stupor.

With his nuanced character study of the male Wanderer, baritone Tyler Boque offers a standout performance. His strained, memory-jogging repetitions of “I…I…I…” perfectly convey the atmosphere of tip-of-the-tongue ineffability that pervades this opera. The moment he drinks the water is exquisite in its subtlety. Every “oh” and “ah” as his past comes flooding back feels genuinely spontaneous, while the quizzically rising scoops at the ends of phrases suggest he’s concealing crucial details. Beneath the gentle exterior of his delivery, Boque occasionally exposes a substratum of guile and manipulation—at one point, there’s even a brief flash of violence in his voice that portends his character’s climactic action.

Although this disc stands sufficiently on its own as an audio-only recording, the composer has posted to his website a pair of clips from a film version due for release this summer. Directed by Laine Rettmer and featuring the same cast as the recording, this intriguing cinematic take channels some of the creepier sequences from “Twin Peaks” and “The Shining.”

— Joe Cadigan, 4.05.2024

A chamber opera from John Aylward’s inimitable vision, the 7 selections here bring 4 voices, viola, cello, double bass, electric guitar and electronics that are inspired by the writings of Dante and Joseph Campbell.

“I. Prologue” opens the listen with strong attention to atmosphere, where a soft droning segues into stirring string interaction thanks to Laura Williamson’s precise viola and Iseei Herr’s absorbing cello, and “II. Scene 1” follows with wordless vocals mixed with firm storytelling that unfolds with much expressive detail.

“IV. Scene 3” and “V. Scene 4” occupy the middle spots, where the former quivers with intimacy that showcases a duo like presence between Ning Guo’s soprano and Daniel Lippel’s electric guitar, while the latter spotlights Greg Chudzik’s meticulous contrabass that helps cultivate the moody climate. “VII: Scene 6” exits the listen with forceful strings and dynamic push and pull amid the strings and the fluid, soaring vocals.

Aylward handles electronics across the listen, and it adds a very unique angle to the chamber nods that populate this fantastical tale of harmonic, haunting and rich songwriting.

— Tom Haugen, 5.06.2024