Richard Cameron-Wolfe's Passionate Geometries features eight of his chamber works written over a thirty year period, displaying the wide range of aesthetic approaches at play in his music, from his theatrical micro-operas to deeply felt settings of instrumental works that explore microtonality. Cameron-Wolfe's musical voice is rarefied and unique in its precise detail, injecting pathos and brilliance into the smallest of gestures as they come together to convey rich narratives.

| # | Audio | Title/Composer(s) | Performer(s) | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time | 71:24 | |||

| 01 | Heretic | Heretic | Marc Wolf, guitar | 15:20 |

| 02 | Time Refracted | Time Refracted | Caleb van der Swaagh, cello, Gayle Blankenburg, piano | 10:36 |

| 03 | Mirage d’esprit | Mirage d’esprit | Oren Fader, guitar, Daniel Lippel, guitar, Jay Sorce, guitar, Matthew Slotkin, guitar | 5:48 |

| 04 | O minstrel | O minstrel | Stephanie Lamprea, soprano, Daniel Lippel, guitar | 4:19 |

| 05 | Telesthesia: 13 episodes/deliberations on multi-planar syzygy | Telesthesia: 13 episodes/deliberations on multi-planar syzygy | Antwerp Cello Quartet, Shuya Tanaka, cello, Jan Sciffer, cello, Peter Devos, cello, Cèlia Brunet Vila, cello | 10:14 |

| 06 | Kyrie(Mantra)IV | Kyrie(Mantra)IV | Roberta Michel, flute, Daniel Lippel, guitar | 9:09 |

| 07 | Lonesome Dove: a True Story | Lonesome Dove: a True Story | Geoff Landman, tenor saxophone, Umber Qureshi, watcher | 7:07 |

| 08 | Passionate Geometries | Passionate Geometries | Nina Berman, soprano, Roberta Michel, flute, Daniel Lippel, guitar, Caleb van der Swaagh, cello | 8:51 |

“I want to tell you what’s going on here. You don’t want to know… Is art just a substitute for what we’ve lost?” In his micro-opera Heretic, Richard Cameron-Wolfe’s enigmatic protagonist breaks the fourth wall, and in the process gives us a window into his artistic vision. Through exploration of dramatic and narrative subtlety in his micro-operas and text settings, expressive shadings of pitch in his use of microtonality, and finely etched treatment of timbre and gesture, Cameron-Wolfe reaches for the ineffable, something embedded in what we’ve “lost” or perhaps an essence of something that we can never possess. Throughout these chamber works, written over a thirty year period, we hear him calibrating his expression towards the mystery that lives between and beyond the sounds, obscuring the transparent surface in favor of the ambiguities of creative uncertainty.

Heretic introduces the listener to a format that has become a core component of Cameron Wolfe’s work, the dramatic micro-opera for one performer. Performed with precision by guitarist Marc Wolf, also the score’s diligent editor, the piece demands an embodied dramatic performance alongside, and often concurrent with, the intricate instrumental part. Cameron-Wolfe engages with the inherent tension between live performer and audience and the balance between inward and outward impulses in art making. The guitar part is woven into the wide ranging vocal part, including wordless vocal effects, spoken dramatic text, and sung passages.

Read MoreOriginally conceived as a piece to be choreographed and performed with dancers, the pacing and organization of Time Refracted for cello and piano reflects that initial intention. Cameron-Wolfe establishes a quietly enveloping pad from the opening, in alternating gestures between oscillating figures in the piano and poignant double stops in the cello. One can imagine dancers responding to the moment to moment dialogue of ideas as well as the overall searching quality that pervades the piece.

Opening with the same quartal harmony that begins Heretic, Mirage employs an alternate tuning of instruments with a standard fretting setup, achieving a scale of 48 equal divisions of the octave through the four guitars. His use of the microtonal tuning goes beyond local expressive color, becoming a structural pillar for the unfolding rhetoric of the piece, developing ideas through microtonal variations across the ensemble. A folkloric melody characterized by an upright dotted rhythm is distorted through an “out of tune” presentation and rhythmic diminution and wobbling bent notes are punctuated by pointillistic interjections.

O Minstrel appears on its own in this collection, but is also the opening movement of a chamber cantata for soprano and ensemble. The ritualistic song sets a text by 13th century Sufi poet Fakhruddin Iraqi entreating a minstrel to grace the protagonist with the inspiring gifts of art and love. The voice and guitar lines are in equal dialogue, with Cameron-Wolfe using the instrumental line to paint the text with fleet passagework, rich block chords, and haunting tambour gestures.

Telesthesia for cello quartet was written in memory of the composer’s friend Harold Geller who passed away in 2019, and captures the phenomenon of feeling the presence of one we have lost in our ongoing life. As with Mirage, gestural accumulation is achieved by subtle displacement of rhythmic simultaneity and extended vocal and percussive techniques broaden the sonic palette. Telesthesia uses contrasting characters and an episodic structure as its organizing principles.

Cameron-Wolfe’s Kyrie (Mantra) has gone through several iterations; the version heard on this recording was transcribed by Ukrainian guitarist Sergii Gorkusha and effectively integrates components of the prepared piano version. The work is divided by three extended flute solos, the first is an evocative introduction that features extended techniques (the original seed for the piece). The guitar enters with a sound vocabulary that evokes the sound world of the keyboard preparations – polyrhythmic tapping passages, bartok pizzicati, and left hand hammer-ons. The second and third flute cadenzas are separated by a passage of bell-like harmonics in the guitar, and migrate from virtuosic bursts to sustained multiphonics.

The second micro-opera on the recording, Lonesome Dove - a true story for “tenor saxophone, watcher, and portable darkness”, dramatizes an experience Cameron-Wolfe had in graduate school listening to a dove singing in the early morning. While he first thought two birds were singing responsively he eventually realized it was simply one dove relocating and answering itself, creating a spatialized performance of its own song. Cameron-Wolfe embeds this mysterious dialectic into the piece, building implied melodic and timbral counterpoint into the saxophone part, as well as planning a mobile staging wherein the performer, a dancer, and an eight foot tall black screen move to simulate the unseen movement of the dove.

In Passionate Geometries for soprano, flute, cello, and guitar, Cameron-Wolfe re-engages with the theme that underlies Heretic, the nature of and desire for the “poetic life.” Here, he sets his own text about a poet who is struggling with a crippling writer’s block under the weight of earthly disappointment. Cameron-Wolfe divides the work by using various instrumental combinations: a cello solo opens the piece, a short ensemble passage leads into a duo between soprano and flute, which sets up an instrumental trio phrase, and so on. The two middle strings of the guitar are tuned a quarter tone low to allow for shadings of pitches within that range. Cameron-Wolfe’s ensemble writing alternates between tightly coordinated rhythmic mechanisms and looser, more fluid dialogues with the voice. This dichotomy balances the piece between rigor and expression, an apt analogy for the forces shaping the struggle of our protagonist poet.

— Dan Lippel

Tracks 1-2 & 6-8 recorded at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY, March 2019 (6), June 2021 (7), October 2021 (1), January 2023 (8), May 2023 (2)

Tracks 3 & 4 recorded at Adelphi University, June 2021 (4), September 2022 (3)

Track 5 recorded at MotorMusic, Mechelen, Belgium, June 2023

Engineer: Geert De Deken (avinspire.be/fr)

Recording producer: Richard Cameron-Wolfe

Engineer: Jeremy Tressler (except 5)

Mixing and mastering: Jeremy Tressler (dreamflower.us)

Editing co-producers: Marc Wolf (1), Gayle Blankenburg (2), Daniel Lippel (3, 4, 6, 8), Jeremy Tressler (5), Roberta Michel (6), Geoff Landman (7)

Design, layout & typography: Marc Wolf (marcjwolf.com)

Publisher: American Composers Edition, composers.com

The score for Heretic, edited by Marc Wolf, won the 2024 Revere Award from the Music Publishers Association

Cover Art: Kevin Teare

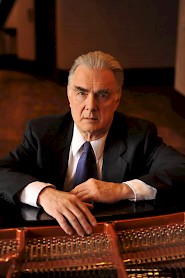

Composer-pianist Richard Cameron-Wolfe was born in Cleveland, Ohio, USA and received his music training at Oberlin College and Indiana University. His principal piano teachers were Joseph Battista and Menahem Pressler; his composition teachers included Bernard Heiden, Iannis Xenakis, Juan Orrego-Salas, and John Eaton.

Composer-pianist Richard Cameron-Wolfe was born in Cleveland, Ohio, USA and received his music training at Oberlin College and Indiana University. His principal piano teachers were Joseph Battista and Menahem Pressler; his composition teachers included Bernard Heiden, Iannis Xenakis, Juan Orrego-Salas, and John Eaton.

After brief teaching engagements at Indiana University, Radford College (Virginia), and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Cameron-Wolfe moved to New York City, where he performed and composed for several major ballet and modern dance companies, including the Joffrey Ballet and the Jose Limon Company. In 1978 he began a 24-year Professorship at Purchase College, State University of New York, teaching music theory and history, composition, and music resources for choreographers. He resigned in 2002 - while he could still walk and think - relocating to the mountains of northern New Mexico in order to dedicate his life to composing.

As a composer, one of his particular interests is micro-opera, a very short theatrical work of 5 to 15 minutes duration, developed through the collaboration of composer, writer (preferably a poet), a scenic/costume designer (preferably a visual artist), and a videographer. The work is intended to be staged in small spaces and could be broadcast on television or the web.

https://composers.com/richard-cameron-wolfeThe human voice is prominent in Passionate Geometries, a collection of composer Richard Cameron-Wolfe’s works spanning three decades for small ensembles. Two of the featured compositions are what Cameron-Wolfe describes as “micro-operas” – brief, dramatic vocal works for a minimal number of performers. But voice in its various dimensions permeates the album and the guitar is prominent as well, as the instrument figures in no less than five of Passionate Geometries’ eight compositions.

“Micro” is indeed the word to describe Heretic, Cameron-Wolfe’s “opera” for a single performer. Guitarist Marc Wolf not only plays an intricate instrumental part, but delivers the text telling us “what’s going on here” (“here” possibly referring to the performance, possibly referring to the world at large) in a mixture of unvoiced exhalation, spoken and shouted word, and singing. The guitar part is fragmentary yet technically difficult, a difficulty no doubt compounded by the guitarist’s having to fill the dramatic vocal role as well.

One of the album’s highlights is the duo O Minstrel, a setting of a text by Fakhruddin Iraqi, the 13th century Sufi poet. This is another work for guitar and voice, albeit of a more conventional sort. Here the guitarist is Daniel Lippel, joined by soprano Stephanie Lamprea. Cameron-Wolfe structured the piece as a dialogue between the two performers, with Lamprea taking the lead and Lippel nimbly responding. The timbral contrast between Lamprea’s liquidly sung lines and the spikier sounds of the nylon-string guitar lend the piece a dramatic tension.

A similar dynamic is at work on Kyrie (Mantra) IV, another standout piece. This duet for flute and guitar is played by flutist Roberta Michel with Lippel on guitar once again. Like the other compositions on Passionate Geometries this is a demanding virtuoso piece. Cameron-Wolfe has Michel bending and slurring notes suggesting the sound of a shakuhachi; overblowing; playing multiphonics and voiced notes; and further drawing on a rich vocabulary of extended techniques. Lippel responds with his own repertoire of extended playing, leveraging tapping, left-handed plucking, snap pizzicato, and harmonics that foreground the staccato precision of the nylon-string guitar’ articulation. Cameron-Wolfe originally wrote the piece for prepared piano; the essence of that instrument’s perverse percussiveness is effectively conveyed by the guitar part in particular.

Mirage d’Esprit is an intriguing microtonal work for four guitars tuned to yield an octave of 48 equal divisions. The guitars’ tunings produce strange choric effects, creating harmonies that can be disorienting at times, but not to worry: as the spoken interjection in the middle of the piece asserts, “it is real.” Telesthesia is another work for four instruments of the same type, this time cellos. The episodic work was written in memory of a friend of the composer’s; it blends movingly somber harmonies with extended instrumental techniques as well as wordless vocal gestures.

Passionate Geometries also includes the title composition, a “micro-opera” for soprano, flute, guitar, and cello; Lonesome Dove for solo tenor saxophone, dancer, and moveable screen; and Time Refracted, for cello and piano.

— Daniel Barbiero, 7.04.2024

There is abundant imagination in these eight chamber works by Richard Cameron-Wolfe but sometimes a winding path to appreciating them. In his composer’s note he makes clear that this is a legacy project spanning three decades from 1992 almost to the present. During that time, Cameron-Wolfe laid down long experience with micro-operas, a new term to me. The three examples offered here feature only a solo singer (sometimes not even a singer), which pushes the boundary of what we typically call an opera, although there is a famous precedent, Poulenc’s La voix humaine. Also unusual are two quartets creating their own sound worlds, one for four guitars, the other for four cellos. Most examples in the genre consist of arrangements.

All of this will intrigue general listeners who possess some curiosity. What makes things more difficult is that Cameron-Wolfe belongs to the experimental wing of New Music, which leads to a challenging listen unless you are willing to go wherever his ear leads, however strangely. In the case of Heretic, the first micro-opera on the program, many performers resisted what Cameron-Wolfe calls a “cursed” piece. “Heretic, commissioned and composed in 1994, [was] rejected by its commissioner and a nearly 20-year procession of other guitarists.”

One reason for rejection is that the score calls upon the guitarist to multitask as an actor, vocalist, and percussionist. The enthusiasm of Marc Wolf for these overlapping roles led him to serve as Heretic’s editor, arriving by stages at the current 2023 version. If you let Heretic roll over you passively, it is quite accessible. That’s not true if you attempt to penetrate the libretto, which is abstract and full of quixotic changes. The central character, the Heretic, plays off other personas—Someone Else, Entity that has “invaded” the Heretic—all three uttering a disconnected stream of free associations.

I appreciate the composer’s sincere efforts to explain his intentions, but confusion seems to be the point. (“Is [the Heretic] performing or rehearsing? Is he communicating with us? … Are we only imagined by the Heretic? Or are we voyeurs, watching through a one-way glass?”) I regret remaining in the dark, because Wolf gives a bravura performance, and the guitar part per se is quite appealing. We move into the terrain of multi-media with Lonesome Dove: A True Story, which has no story and defies the label of micro-opera since there is no vocalist—the scoring is for “tenor saxophonist, watcher, and portable darkness.”

In essence this is music for a dancer and unaccompanied saxophone (Geoff Landman). Deprived of visuals, we sparingly hear footsteps and strange vocals from the “watcher” or breathy gestures from the saxophone. The libretto can be quoted in full. “Squawk… squawk, squawk/ Hmm… scream… scream grrrrrrrr… grrrr, grrrrrrr / No, I am alone.” Your response will depend on an appetite for pure experimentalism, but the tenor sax part makes agreeable listening. The third micro-opera is the title work, Passionate Geometries, the only example that employs a conventional singer (soprano Nina Berman), accompanied by a small ensemble of flute, guitar, and cello.

In Cameron-Wolfe’s conception, the piece revolves around the singer’s aspiration for a poetic life as expressed through interactions, “collisions as well as embraces,” between the performers. In their way the instrumentalists are onstage characters. The libretto is adapted from an early poem by the composer, again in free-association mode. But thanks to his ingenious writing for the four participants, Passionate Geometries is a success at communicating itself expressively—my attention was held throughout.

As is evident by now, it takes a lot of words just to set down basic descriptions of some very disparate works, and I’ll be brief from now on. The guitar features prominently in five of the eight works on the program. The most intimate are two duos. O Minstrel for soprano and guitar, described as “songs from the cantata ‘Breathless.’” The text is based on Sufi poetry. Purely instrumental is Kyrie(Mantra)IV for flute and guitar, the fourth variant of a solo flute piece dating back to 1972. Both duos are atmospheric and evocative.

The underpinning of the guitar quartet Mirage d’esprit is technical. “In this work, I made the transition from using microtones as a resource of expressive nuance to fully creating a work with a microtonal pitch-set of 48-EDO (48 equal divisions of the octave).” The spare, transparent interplay of plucked microtones, which at times faintly echo Indian classical music, becomes the core experience, since no formal plan is readily detected, but there are also cries of “This is real,” “Go!”, etc., along with thumps on the guitar case. The effect lies somewhere between incomprehensibility and the entertainingly outré (not a bad way to encapsulate the entire album).

The cello features in three works, including a cello quartet with the cryptic title Telesthesia: 13 episodes/deliberations on multi-planar syzygy. The explanation involves a close friend in northern New Mexico who died in 2019, after which Cameron-Wolfe had many sighting of him in spectral form, one might say. The cello’s voice is naturally elegiac, which this work takes eloquent advantage of in tonal harmonies while creating another face through ghostly intimations that employ wordless vocalizing and extended instrumental techniques.

They are familiar parts of the composer’s toolbox, which he turns to new uses from piece to piece. I found myself being immediately involved in Telesthesia, appreciating it as a moving memorial as well as musically captivating. I hope it enters the repertoire of contemporary cello ensembles—it deserves to. The performance by the Antwerp Cello Quartet is exemplary, which holds true for all of the top-flight musicians here.

Nothing on the program is less than arresting, inventive, and original. One also has the sense that Cameron-Wolfe lives like a musician without borders as a pianist, teacher, writer, theorist, and musical ambassador to faraway places. It sounds like a heady existence, not to mention that on more than one occasion he has played Satie’s 24-hour Vexations for piano. As a legacy album, this one serves its purpose admirably.

Four stars: Disparate chamber works from a long, highly original career

— Huntley Dent, 7.24.2024

In the 21st century, chamber music is often considerably more ambitious than it was in the 18th, and is only rarely created as any sort of “background” material. Today’s composers tend to use reduced-size ensembles to make specific points that they feel are better communicated with fewer performers. Richard Cameron-Wolfe (born 1943), for example, creates some chamber works for only one performer, but expects that individual to assume multiple roles. A New Focus Recordings release of Cameron-Wolfe’s chamber music leads off with just such a piece: Heretic, which the composer labels a “micro-opera” in which he collaborates with a visual artist, videographer and writer. This type of piece lasts five to 15 minutes and is designed to be staged in a small space, which certainly echoes the “chamber” part of “chamber music.” But the effect of a piece such as Heretic is quite different from that of more-traditional chamber music. Marc Wolf performs it as narrator, vocal artist, guitar player and percussionist, and even without the visual element – inevitably absent in CD form – it is clear that this is intended as a dramatic play with music, using wordless effects as well as spoken text along with the instrumental material. The CD contains another “micro-opera” called Lonesome Dove: a True Story, featuring Geoff Landman on tenor saxophone and Umber Qureshi as the “watcher,” a role invisible in this recording but clearly integral to the bird-observing experience that Cameron-Wolfe seeks to illustrate both visually and with the usual techniques of avant-garde musical production. Virtually all the works on this (+++) recording have theatrical elements. Time Retracted for cello and piano was designed for dancers. Mirage d’esprit for guitar quartet uses microtonal tuning and requires technique that would be highly watchable in performance. O minstrel for soprano and guitar is part of a chamber cantata and is unusually attentive to the text for a work in strongly contemporary guise. Telesthesia: 13 episodes/deliberations on multi-planar syzygy for cello quartet is one of those deliberately over-titled pieces whose overstuffed name is attached to some surprisingly moving string writing – the piece is a memorial written after the death of a friend of the composer. Kyrie(Mantra)IV is another of those overdone-title works so common in the oeuvre of many modern composers, and features flute-and-guitar scoring that gives the constant impression of electronic amplification even when none is present. And Passionate Geometries for soprano, flute, guitar, and cello, using a text by Cameron-Wolfe himself, rather unconvincingly attempts to explore the mind of an angst-ridden poet with writer’s block – a cliché if there ever was one. Cameron-Wolfe’s insistent theatricality is more distinctive than any specific compositional style in these pieces, which collectively and individually blend into a kind of modernistic assemblage that is similar to the work of many other composers who may wish to be forward-looking but who effectively merely look askance at the traditions of chamber-music creation and performance without really expanding them in any meaningful way.

— Mark Estren, 8.29.2024

Richard Cameron-Wolfe is probably best known for his micro-operas – powerful pocket-size, single-movement pieces for solo, duet or small ensemble combinations that explore musical, cognitive and dramatic dissonances through the lens of the composer’s hard-hitting atonal and microtonal style.

Passionate Geometries is bookended by two of these micro-operas. The first, Heretic, revolves around a dysfunctional dialogue between solo guitar and the performer’s own voice (both elements impressively coordinated on this recording by Marc Wolf), where vocal and instrumental fragments combine to generate wildly contrasting moods and gestures – from relaxed and friendly to fractious, frenzied and chaotic. Think Elliott Carter on Quaaludes to get a general sense of the music’s impact.

The title-track, for soprano, flute, guitar and cello, offers a more muted and withdrawn take on Cameron-Wolfe’s micro-operatic aesthetic. Even when writing for ensemble, however, Cameron-Wolfe builds his material around solo statements and duet combinations. The music is often at its most effective when the soloist becomes entangled in a kind of schizophrenic soliloquy with itself (as happens in Heretic) or where subject and object are pitted against one another.

A sinister and uneasy undertow lurks beneath the surface of Time Refracted for cello and piano – its title reflected in ticking clock-like oscillations and uneasy, shifting patterns – while echoes of Wagner’s Tristan chord hover stubbornly, like a dark cloud, over the musical landscape of O minstrel for soprano and guitar.

Cameron-Wolfe’s music is perhaps less effective when the focus is on group dynamics rather than dramatic conflict. Such moments are encountered in the microtonal Mirage d’esprit and fragmentary Telesthesia, for guitar and cello quartets respectively, where sonic weirdness takes precedence over substance and content. Nevertheless, with eye-catching contributions from soprano Stephanie Lamprea in O minstrel, flautist Roberta Michel in Kyrie(Mantra)IV, saxophonist Geoff Landman in Lonesome Dove: A True Story (another Cameron-Wolfe micro-opera) and the ever-present Dan Lippel on guitar, Passionate Geometries provides a timely overview of the chamber output of this under-the-radar composer, forming an excellent companion album to An Inventory of Damaged Goods, issued on the Furious Artisans label in 2018.

— Pwyll ap Siôn, 11.07.2024

This expansive collection presents thirty years of chamber works and finds Cameron-Wolfe a jack of all trades and a master of all, from the guitar solo (Marc Wolf) “opera,” Heretic, to O Minstrel, which sets a 13th century Sufi poem and inspires an awesome performance by soprano Stephanie Lamprea. We also get a guitar quartet, a cello quartet, and other creatively arranged and composed works that show off the composer’s questing nature as he searches for the “poetic life.” Who wants to tell him to look at the end of his pen (or composing software)?

— Jeremy Shatan, 1.17.2025

Richard Cameron-Wolfe is a composer divided, or it might be better to say that he is a composer who practices transcendent divisiveness. There are composers whose works exude a calm reflectivity achieved through unity. Cameron-Wolfe shares with them a unified vision, but it is achieved through various dialogs via an often confrontational look inside the fractured body-mind relationship, the psyche in search of that which makes it unique. His new album, Passionate Geometries, foregrounds his unique approach to a searching spirit in dialectical quest.

To demonstrate, it may be best to focus in some detail on a couple of the eight works presented here. Heretic, one of the pieces which Cameron-Wolfe calls micro-operas, drives the point home, encompassing all the extremes of the search in about 15 minutes. Composed over a period of 30 years and undergoing various revisions, its stunningly virtuosic conception involves guitar, voice, and percussion, all of which falls to Marc Wolf. It’s always the composer’s prerogative to suggest that a performance is definitive, but it’s difficult to imagine a better one than this. From the opening moments of staggered tone and exhalation, Wolf purveys the opposing and comingling forces of heretic and the various entities in conflict. At one point, the heretic asks: “Is art just a substitute for what we’ve lost?” Each musical phrase comes across as a similar question, or the fragment of an answer. The torrents of guitar notes at 3:49 that it would be foolish, or at least incomplete, to label arpeggiations or runs, though they resemble both, give instrumental voice to the surrounding interrogations and observations. The proverbial fourth wall is at least transparent as the heretic nearly murmurs: “But I feel better when I do this ... even with the wrong notes, what’s the difference?” Amid the stunningly virtuosic writing, singing, and knocking that resembles Stockhausen’s protagonist knocking at Heaven’s door, there’s something so heartbreaking in the directness, the simplicity amid all the complexity as endings are sought but never really achieved, leaving only a gradually detuned note in conclusion.

Bookending this superb disc is the titular piece, another micro-opera based on a poem by the composer. Soprano Nina Berman, flutist Roberta Michel, guitarist Daniel Lippel, and cellist Caleb van der Swaagh offer up yet another excellent performance of a similarly evocative score with the first line of text reading, “The eye betrays the body.” It is as if, from jump street, the poetic instinct necessitates, or causes, fracture as even bodily elements turn against those supposedly considered colleagues. The instrumental parts betray similarly fragmented allegiances, the flutes conjuring shades of everything from Pierrot-era Schoenberg to the windy percussiveness of Takemitsu. Even these non-conventions are occasionally flouted by moments of rather traditional though perfectly reasonable convention, like the musical echoes following the word “echo.”

The playing is superb throughout this well-filled disc, but exactly what sort of music is this? Where does it fit, in what way, and for whom are these vast dynamic shifts and motivic pointillisms meant? The titular poem’s “word” seems to hold the key. At the conclusion of Moses und Aron’s second act, Moses finds himself in the dire situation of attempting to resolve the unresolvable. Schoenberg’s music, a single pitch in the strings played as Moses sinks despondently to the ground, prefigures Cameron-Wolfe’s own, though the latter’s message should not be taken as a negative. As contradictory as it can be, as confrontational as its narrators might appear as they face internal and external division, the act of documenting such a vision is itself a positive. This is music of raw power and overwhelming beauty in rapid-fire juxtaposition. It rewards repetition and, like the repeatedly plumbed depths of lived experience it embodies, should be experienced in the spirit of honesty and strength from which it springs.

— Marc Medwin, 3.01.2025

Born in 1943, Ohio-born Richard Cameron-Wolfe studied at Oberlin and Indiana University, and numbers Iannis Xenakis as one of his teachers.

The first piece seems to have some Occultist basis: The very first word is an (interrupted by “Someone Else”) Tetragrammaton, which is the fourfold name of God gleaned from the four Hebrew letters Yod Heh Vav Heh (YHVH, or Yahveh). The text also mentions a known Occultist, Arthur Machen—specifically, his The Hill of Dreams, which the London Review of Books once stated was viewed as “an intoxicating and unwholesome mix of drug addiction, sensuality, and sadomasochism, with hints of paganism and witchcraft.” The protagonist states that Machen’s text “sheds some light” on his sense of unreality, all underpinned by roiling guitar arpeggios. The whole piece is steeped in secrecy: Just when we, the audience, feel we will be told the whole story, we are told that we “do not want to know.” That secrecy extends to the idea of a solo working (“Leave me alone ... This is only my atonement”). There is a lot of metaphorical patting of one’s head and rubbing of one’s stomach here. The work is heard in a performance score edited by the present performer, the incredibly talented Marc Wolf, who is listed as performing “guitar, voice, percussion & narration.” The piece began life in 1994; the version we have here is from 2023.

A duo for cello (Caleb van der Swaagh) and piano (Gayle Blankenburg) from 1990, Time Refracted, was originally written for the dance but exists in a purely chamber music format. The piece includes a “prismatic array of prime-number generated phrase lengths and rhythmic activity.” There are certainly many contrasts here, effectively caught and projected by the performers. We are invited to “imagine the dancers,” but actually the piece as it stands is captivating, with its (intended) freedom and independence of the two performers.

The soft sound of a guitar quartet is the basis for Mirage d’esprit (Spirit Message) of 2019. Oren Fader, Daniel Lippel, Jay Sorce, and Matthew Slotkin are the intrepid performers here. When called to do so, they play as if they are one super-guitar; at others, their near- collisions invoke a gamelan. The scale used is comprised of 48 equal divisions, which seems to contribute to an Orientalist implication. There is the occasional verbal interruption, but this is primarily an instrumental piece.

The song “O minstrel” comes from the cantata Breathless and dates from 2012. The pure-voiced Stephanie Lamprea is the soprano soloist, and Daniel Lippel the guitarist. The text is by the Persian Sufi poet Fakhruddin Iraqi (1210–1289, also transliterated as “Fakhr al-Din Iraqi.” The elusive, mystical text suits the insubstantial scoring (which perhaps reflects the search for a nonphysical other space). It is highly beautiful in a disjunct way. Far more traditionally beautiful is the opening of Telesthesia from 2019, for cello quartet (here, the Antwerp Cello Quartet), boasting a rather forbidding subtitle of “13 epi- sodes/deliberations on multi-planar energy.” Intended as a tribute to the artist Harold Geller, the subtitle refers to the many “sightings” of the deceased by the composer after Geller’s death. There are disturbances in the piece’s fabric of beauty, perhaps reflecting the stages of bereavement (one could also posit that the “specters” he sees are aspects of the stage of bereavement known as “denial”). The sound palette conjured by Cameron-Wolfe is, as might be by now expected, wide, but here held within an in memoriam field.

Moving to a piece for flute and piano ushes in new sonic territory: Kyrie (Mantra) IV of 2016, performed by Roberta Michel (flute) and Daniel Lippel (guitar). Michel has the most beguiling sound and huge technique (there are, again unsurprisingly, multiphonics at play here). The piece is captivating, one of several variants on a work originally written in 1972 for flute trio. The second version was for flute and prepared piano, the third (withdrawn) for flute and guitar. The piece is edited by Sergii Gorkusha and it is the final one in the cycle. Parts of the original piece for flute trio find their way into the guitar part. There are surprises here, not least when the flute and guitar threaten to move into traditional melody with traditional accompaniment, though the moment is short-lived; instead, the flute embarks on an avian cadenza.

The 1992 piece Lonesome Dove—A True Story is, like Heroic (and the piece to come, Passionate Geometies), a “micro-opera,” performed by Geoff Landman on tenor sax. There is also a “Watcher” (Umber Qureshi) whose part is by necessity here nonvisual and whom we hear in footstep and vocals. There are actually three scenes: “Looking for love,” “My Onan only,” and “I/Thou ... why now?”. The dove of the title is heard (and we do hear it here, both in sax squeaks and vocal ones too) at around 4:00 am on a sleepless night by the composer. A “second dove” responds to the first, and a duet is born—except that it turns out when light dawns that there is only one dove. It’s a beautiful story, bought to musical life in a piece that proves that squeaks and squeals can be lyrical, too. The performers here are exceptional.

The final “micro-opera,” Passionate Geometries, dates from 2019 and features soprano (Nina Berman), flute (Roberta Michel), guitar (Daniel Lippel), and cello (Caleb van de Swaagh). The libretto is taken from a poem by the composer himself, written in 1979. The protagonist wishes to live “poetically”; against her is the World, which acts as a grounding element, offering “mundane sensory limitations and earthy disappointments.” In performance, there is a mime onstage—but again, we either have to imagine or to discard. Again, there is an Occultist reference, this time to “initiates.” The instrumentalists are each as much virtuosos as the singer; the control of the cellist is most remarkable. Even more impressive is how this remains a compelling experience in the absence of visuals, particularly of the mime artist. Nadia Berman is an extraordinary artist and singer: Those moments when Cameron-Wolfe clearly wishes the voice to function as another instrument are delivered with pinpoint accuracy.

The physical booklet does not include texts; those are accessible via a QR code. The whole disc is a revelation: Richard Cameon-Wolfe’s voice needs to be heard more often. His music absolutely demands concentration, but rewards the effort in spades. This is a Want List candidate, for sure.

— Colin Clarke, 3.01.2025

There is abundant imagination in these eight chamber works by Richard Cameron-Wolfe, but sometimes a winding path to appreciating them. In his composer’s note he makes clear that this is a legacy project spanning three decades, from 1992 almost to the present. During that time Cameron-Wolfe laid down long experience with micro-operas, a new term to me. The three examples offered here feature only a solo singer (sometimes not even a singer), which pushes the boundary of what we typically call an opera, although there is a famous precedent, Poulenc’s La voix humaine. Also unusual are two quartets creating their own sound worlds, one for four guitars, the other for four cellos. Most examples in the genre consist of arrangements. All of this will intrigue general listeners who possess some curiosity. What makes things more difficult is that Cameron- Wolfe belongs to the experimental wing of New Music, which leads to a challenging listen unless you are willing to go wherever his ear leads, however strangely.

In the case of Heretic, the first micro-opera on the program, many performers resisted what Cameron-Wolfe calls a “cursed” piece. “Heretic, commissioned and composed in 1994, [was] rejected by its commissioner and a nearly 20-year procession of other guitarists.” One reason for rejection is that the score calls upon the guitarist to multitask as an actor, vocalist, and percussionist. The enthusiasm of Marc Wolf for these overlapping roles led him to serve as Heretic’s editor, arriving by stages at the current 2023 version. If you let Heretic roll over you passively, it is quite accessible. That’s not true if you attempt to penetrate the libretto, which is abstract and full of quixotic changes. The central character, the Heretic, plays off other personas— Someone Else, and an Entity that has “invaded” the Heretic—all three uttering a disconnected stream of free associations. I appreciate the composer’s sincere efforts to explain his intentions, but confusion seems to be the point. (“Is [the Heretic] performing or rehearsing? Is he communicating with us?... Are we only imagined by the Heretic? Or are we voyeurs, watching through a one-way glass?”) I regret remaining in the dark, because Wolf gives a bravura performance, and the guitar part per se is quite appealing.

We move into the terrain of multimedia with Lonesome Dove: A True Story, which has no story and defies the label of micro-opera since there is no vocalist—the scoring is for “tenor saxophonist, watcher, and portable darkness.” In essence this is music for a dancer and unaccompanied saxophone (Geoff Landman). Deprived of visuals, we sparingly hear footsteps and strange vocals from the “watcher” or breathy gestures from the saxophone. The libretto can be quoted in full. “Squawk ... squawk, squawk / Hmm ... scream ... scream grrrrrrrr ... grrrr, grrrrrrr / No, I am alone.” Your response will depend on an appetite for pure experimentalism, but the tenor sax part makes for agreeable listening.

The third micro-opera is the title work, Passionate Geometries, the only example that employs a conventional singer (soprano Nina Berman), accompanied by a small ensemble of flute, guitar, and cello. In Cameron-Wolfe’s conception, the piece revolves around the singer’s aspiration for a poetic life as expressed through interactions, “collisions as well as embraces,” between the performers. In their way the instrumentalists are onstage characters. The libretto is adapted from an early poem by the composer, again in free-association mode. But thanks to his ingenious writing for the four participants, Passionate Geometries is a success at communicating itself expressively—my attention was held throughout.

As is evident by now, it takes a lot of words just to set down basic descriptions of some very disparate works, and I’ll be brief from now on. The guitar features prominently in five of the eight works on the program. The most intimate are two duos, O Minstrel for soprano and guitar, described as “songs from the cantata ‘Breathless.’” The text is based on Sufi poetry. Purely instrumental is Kyrie (Mantra) IV for flute and guitar, the fourth variant of a solo flute piece dating back to 1972. Both duos are atmospheric and evocative.

The underpinning of the guitar quartet Mirage d’esprit is technical. “In this work, I made the transition from using microtones as a resource of expressive nuance to fully creating a work with a microtonal pitch-set of 48-EDO (48 equal divisions of the octave).” The spare, transparent interplay of plucked microtones, which at times faintly echo Indian classical music, becomes the core experience, since no formal plan is readily detected, but there are also cries of “This is real,” “Go!”, etc., along with thumps on the guitar case. The effect lies somewhere between incomprehensibility and the entertainingly outré (not a bad way to encapsulate the entire album).

The cello features in three works, including a cello quartet with the cryptic title Telesthesia: 13 episodes/deliberations on multi-planar syzygy. The explanation involves a close friend in northern New Mexico who died in 2019, after which Cameron-Wolfe had many sightings of him in spectral form, one might say. The cello’s voice is naturally elegiac, which this work takes eloquent advantage of in tonal harmonies while creating another face through ghostly intimations that employ wordless vocalizing and extended instrumental techniques. They are familiar parts of the composer’s toolbox, which he turns to new uses from piece to piece. I found myself being immediately involved in Telesthesia, appreciating it as a moving memorial as well as musically captivating. I hope it enters the repertoire of contemporary cello ensembles—it deserves to. The performance by the Antwerp Cello Quartet is exemplary, which holds true for all of the top-flight musicians here.

Nothing on the program is less than arresting, inventive, and original. One also has the sense that Cameron-Wolfe lives like a musician without borders as a pianist, teacher, writer, theorist, and musical ambassador to faraway places. It sounds like a heady existence, not to mention that on more than one occasion he has played Satie’s 24-hour Vexations for piano. As a legacy album, this one serves its purpose admirably.

— Huntley Dent, 3.01.2025

In an essay written earlier this year to accompany a 54-year retrospective concert of his works, composer/pianist/poet Richard Cameron-Wolfe asks, “Why do I continue a creative life?” Perhaps his new CD, Passionate Geometries, covering a 30-year slice of that greater span, provides, if not definitive answers, testimony to his ongoing quest to “compose what I want to hear,” to summon “geometries” hovering beyond the mundane through art. Biographical details, recollections of travels, performances, mentors and colleagues provide additional clarification.

While preparing for our conversation I came across two quotes that offer clues about your early years as an aspiring composer: “In 1968, with little previous experience, I petitioned to be accepted into the Indiana University Master’s degree program in composition.” I take it that “little previous experience” refers to composition. Had you previously earned a Bachelor’s degree in a related musical specialty?

Yes, my undergraduate degree (begun at Oberlin College and completed at IU) was in piano performance.

The second significant excerpt concerns your response to discovering the poetry of Bill Knott: “I was introduced to his writing in the late 1960s by multidisciplinary artist Franz Kamin, and Knott’s poetry quite literally awakened in me the desire to become a composer.”

Long story: In 1967 (at IU) I was preparing my senior recital and—at the urging of my pianist friend Kevin Kline—was studying acting with then graduate student Harold Guskin. And I had become involved with the off-campus multidisciplinary group FIASCO. There, upon devouring Knott’s collection The Naomi Poems, I became obsessed with his poem titled “Death” and Franz Kamin encouraged me to set it to music. I did so, for narrator, bassoon, trombone, and double bass, and it was premiered at a FIASCO Sunday afternoon gathering, with Harold as the narrator. (You will find it on my 2018 Inventory CD, narrated by Kevin.)

Where were you headed in music before that “awakening?”

My parents were self-trained musicians: my mother played mandolin, my father harmonica. My first access to a piano (at age six) was in the home of our next-door neighbors, whose immense upright served only as living room furniture. Their daughters would walk me to and from school, and on the way home I’d join them for cookies and milk. I became fascinated with the instrument—not for musical reasons, but as a resource of resonant power. After a few weeks of crashing, booming chaos, the piano was moved into our house.

From ages seven to 11 I studied piano with Ladd Prokesh in Cleveland, OH, playing pop music with him and receiving a strong foundation in technique, harmony, and improvisation.

Show tunes were notated on big file cards—melodies on a treble staff with chord names (e.g., Gm, D7)—and I was encouraged to devise my own “arrangements.” Such fun! It remained a recreation, though, as my primary interest was in science, particularly chemistry.

In 1955 we moved to the Cleveland suburb of Parma and searched for a new piano teacher. The nearby music shop welcomed me but regretfully explained that its pop music teacher had a full schedule of students and was becoming locally famous as a jazz musician. “We could place you with our classical piano teacher, however. Would you like to give it a try?” I agreed and commenced lessons with Bruce McIntyre, discovering Bach and Chopin. A powerful obsession enveloped me, and my chemistry set (much to my parents’ relief) was exiled to our attic. The piano became my anchor and raison d’être.

At age 15 I gave my first public solo recital, and also performed the Schumann Piano Concerto with McIntyre’s orchestra. Thereafter, I studied with McIntyre’s teacher, Leon Machan, who had been the Cleveland Orchestra’s pianist under Artur Rodziński. Machan prepared me for college auditions, so off to Oberlin I went in 1961 (on full scholarship). My identity as a classical pianist was confirmed. Unfortunately, my Oberlin piano professor and I were incompatible, and I dropped out, with a serious hand injury, seven weeks into my senior year. Six months later I played a dreadful audition at Indiana University, still injured, but was accepted (rescued) by one of the auditioning faculty, Joseph Battista.

You’ve dedicated all your piano works to your sister, who performs on your Passionate Geometries CD. Did you both study with the same teacher?

My dear kid sister Gayle began studying with Bruce McIntyre in 1956 after camping out under our piano for a couple years while I practiced. She came to IU as a piano major in 1967 and began an illustrious piano life there just when I was “bitten by the Muse” and began composing. Except for a two-piano performance of the Henselt Concerto we didn’t really collaborate, however, until the 1980s, when I started composing piano pieces for her.

Going back for a moment to my transition from piano to composition, in 1968 I showed the pieces I had composed for FIASCO to Indiana University Professor Bernhard Heiden, and he accepted me into the master’s program in 1969. I became a double major, performed my master’s recital while studying under Menahem Pressler in 1973, and began a doctorate in composition, studying then with microtonalist John Eaton and Iannis Xenakis during his brief IU sojourn.

Under Eaton’s influence you began to embrace microtonality, writing music using more than the traditional 12 divisions of the octave, and eventually composed Mirage d’esprit, in which you “made the transition from using microtones as a resource of expressive nuance to fully creating a work with a microtonal pitch-set of 48-EDO (48 equal divisions of the octave).” What appeals to you about this type of sound? Were you inspired by the prevalence of microtones in various non-Western traditions or by composers like Harry Partch? How does the Kharkiv Guitar Quartet play these intervals, as a guitar neck is normally only subdivided into whole and half tones?

As with my mentor John Eaton, being a pianist was a life experience enslaving me to 12-pitch tempered tuning. John was a jazz pianist and was frustrated that he could not produce “blue notes” the way his bassist and wind players did. I first became suspicious of the tempered scale when I realized that only the octaves were truly “in tune,” all the rest having been “de-tuned” to accommodate their role in various keys. The breakthrough for my microtonal awareness came when John commissioned me to hand-draft a fine copy of his 1971 television opera Myshkin, a score dominated by a 24-pitch quarter-tone vocabulary. I tend to “hear” music as I view a score, and during this arduous two-month project, I began to recognize quarter-tones. As a prolific composer of microtonal operas, John also developed a method for his singers—a microtonal method easy to learn, enabling them to hear and execute microtonal melodies.

Will Western concert music composers ever have an audience as able to hear and appreciate microtonal pitches, melodies, and harmonies as those who have grown up in microtonally endowed non-Western cultures? I doubt it. I collected scores and recordings of microtonal music by Alois Haba and Julian Carrillo, enjoying them for their exotic sound but without an understanding of their aesthetic rationales, while rejecting the notion that I was listening to “out-of-tune” wrong notes.

I hesitated to compose exclusively microtonally for decades, until I was invited to compose my 48-pitch (quarter and eighth tones) Mirage d’esprit for the Kharkiv Guitar Quartet. The guitarists showed me how, with a high-tech tuning gadget, they could accurately tune individual strings up or down microtonally, and I accepted the challenge. Personally, I preferred to employ microtones texturally rather than melodically, using them vertically and in varying densities. I used the same approach in my 2023 guitar sextet Arcturus, this time employing 18- and 36-pitch resources (third and sixth tones).

You’ve also written music “based on the irrational elasticity of the prime-number series.” For example, you’ve said of Time Refracted that it offers “a prismatic array of prime-number-generated phrase- lengths and rhythmic activity.”

In 1972, I met the revolutionary composer-painter-astrologer Dane Rudhyar and commenced a mentorship with him that continued until his passing in 1985. I studied his piano music with him and immediately encountered its complexity of rhythm, texture, and notation. Gone were the pages of historical duple or triple meter, and the multi-metric time-shaping was not ruled by “downbeat” weight or emphasis.

Rudhyar declared his determination to “liberate music from its continuing enslavement to 18th-century dance meters and the tyranny of clock time.” He regretted not being able to find a notation system to accommodate the improvisatory nature of his own performance and accepted that his scores appeared very complex, opposed to the sense of freedom he desired to convey.

I began to realize that, whereas time is measured in absolutes of seconds, minutes, and hours, our experience of it is quite subjective and elastic. (“Where did my weekend go? It’s Monday morning already?”)

I turned to my childhood interest in math, and my fascination with the prime number series. Its irrationality of number sequence seems closer to how we experience time passing (or at least a metaphor thereof). By the mid-1970s, it became (and continues to be) my primary means of time-shaping on the micro- (phrase by phrase) and macro- (section by section) level—subjective, subjectively experienced time.

What role do extended techniques like multiphonics and others play in your music?

Throughout the history of music, the expansion of performing techniques has been continuous, as has been the evolution of instruments to accommodate them. For example, Beethoven, the great innovator, had to premiere his extended techniques Violin Concerto as a Piano Concerto.

If a musician has an “enriched sonic vocabulary,” I’m happy to consider it. If I have a “what if” notion of a sound I’d like to hear and use, I won’t hesitate to sit down with an open-minded musician and see if we can find it and determine its practical accessibility. Then it’s up to me to decide if it is expressively useful in a larger context.

Heretic, your micro-opera for guitar, features an eponymous character who “speaks the unspeakable, thinks the unthinkable, and plays the unplayable.” Would it be farfetched to wonder if you identify with him on some level? Guitarist Marc Wolf, who performs the piece on the disc, seems to think so, as he refers to you as “a proverbial heretic.”

The work was catalyzed by my discovery and reading of Arthur Machen’s “Celtic twilight” novel The Hill of Dreams. I immediately identified with its protagonist, a character whom I personally perceived as a heretic (though others reading it might disagree). Marc read it also. And he knows me as well as just about anyone. If he views me as a heretic, I won’t argue with him.

Where did the idea to write micro-operas come from?

In the context of our 1960s-1970s FIASCO group, interdisciplinary interaction was essential, and the idea of bringing an actor, poet, visual artist, musician(s), and dancer together was too tempting for us to resist.

We needed to be “outside” because “inside” (in academia) one had an academic major, and the demands of that major made it nearly impossible to include enrollment in a course in another art form. When I ultimately abandoned my doctorate, after having two multidisciplinary thesis proposals rejected, I knew I needed to continue exploring and developing the micro-opera genre. What is it? For me, micro-opera is this: a highly concentrated collaborative dramatic theater event of short duration (c. three to 15 minutes), involving a composer, a poet (instead of a formal librettist), a visual artist (instead of a scenic designer and costume designer), one or more musician- instrumentalists (who might take on vocal or dramatic roles/responsibilities), and one or more character-performers (not necessarily including a singer—e.g., an actor, an acting dancer, a mime, or even an acting instrumentalist).

Had you done any acting before studying at IU?

I did some acting in high school, most memorably as the lead in Bettye Knapp’s coming-of-age comedy The Inner Willy (dreadful!). I also sang in the high school choir, where we often included opera scenes in our concerts. At Indiana University I served as rehearsal pianist for numerous productions and sang in the opera chorus, notably in the late-1960s annual productions of Parsifal and in an outdoor production of Carmen (the stage was set up in the football stadium end zone).

Have you ever written a full-length opera?

In the 1980s, I collaborated with then-exiled Guatemalan novelist Arturo Arias on a full-length “Mayan” opera, to be titled Los Caminos de Paxil, which Joseph Papp wanted to include in his Festival Latino. Unfortunately, Arias and I could not agree on the scale of its libretto; I needed a maximum 20- to 25-minute-readable libretto for a two-hour opera, but he provided a short-novel-length script. We couldn’t agree upon how to condense it, then Mr. Papp lost interest, and the project was abandoned. (I still hope to salvage three choruses from the score, their texts written in English, Spanish, and Quiche Mayan. And Arturo did in fact make a novel out of his libretto!)

In addition to writing theatrically oriented micro-operas, you’ve also composed for ballet and modern dance companies, including the Joffrey Ballet and the José Limón Company. And, as we’ve learned, you sometimes include dancers in your other works—for example, Time Refracted, which “was originally composed for choreography.”

When, at age 12, I began to study piano with Bruce McIntyre, my younger sister began studying ballet with McIntyre’s wife. She eventually complained about the “scratchy old records” used in class and convinced the teacher to hire me! I went on to accompany classes and rehearsals in downtown Cleveland at the Ballet Theatre School and the Cleveland Ballet Center. At IU I played for ballet and modern dance classes and rehearsals—most memorably for a c. 1971 production of Giselle starring Ivan Nagy and Natalia Makarova, directed by the legendary Anton Dolin. I also composed three works for the Modern Dance program: Labyrinth, The Dark Cycle, and The Awakening. I devised and taught a Music for Dancers course there as well.

In 1974–75 I had my first professorship, at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, teaching in the Music and Dance departments, where I performed in and composed for the ensemble Music from Almost Yesterday. I then moved to New York City at the invitation of the José Limón Dance Company and commenced a 27-year life in and around the city, playing for dance classes, composing for choreographers and teaching in the Music and Dance departments of SUNY-Purchase for 24 years.

What attracts you to the world of dance?

As a composer, I am fascinated with the performative space offered for music and am devoted to interacting with and resonating in that space.

Looking back over your formative years with FIASCO, how were the group’s proselytizing efforts received?

We had small audiences, a few Beethoven admirers, but mainly folks who had seldom if ever attended a “classical” concert. We pooled our resources to rent a performance space, publicize our event, and pay our courageous performers.

For better or for worse, academia began to catch up with these 20th- century new directions. My 1963 “20th c. Music” course at Oberlin regrettably didn’t make it past WW II, though. But colleges and universities became refuges for innovative composers, shielded from the criticisms of the “real world” classical music establishment—a two-edged sword, to be sure.

An off-campus performance constituted a major achievement, especially if we were invited and externally funded, and it helped to have established ourselves as a named collective: e.g., FIASCO, FOAM (Friends of Aleatoric Music), Collage, Nomads.

By the late 1960s, I became devoted to the important non-mainstream American composers, beginning with Charles Ives and Charles Griffes, and by 1970 I was giving “American Music” lectures and including American music on my piano concerts. In 1974, passing through Taos, NM on my way to teach and perform at an arts camp in Steamboat Springs, CO, I met American composer Noel Farrand and performed on the first of his Ten Lectures on American Music. We created a Friends of American Music organization soon thereafter and an American-music-dominated New Mexico Music Festival, which flourished from 1978 to 1982.

When I began touring abroad in the late 1980s as a pianist-composer- lecturer, my focus was primarily on American music. I often returned with a suitcase of scores and recordings from composers of my host country. I would share the scores with American musicians and eventually, here in the Southwest where I served for several years as DJ of my own “Sunday Morning Un-Classics” radio show, I shared with my listening audience the recordings I’d been gifted with during my European tours. Now and then I fielded an irate caller (one asking if she was hearing a Civil Defense warning signal!). Most recently, I participated in the international microtonal “Small is Beautiful” Composers Symposia at the Mozarteum in Salzburg and shared three “Nomads” concerts here in the USA with Austria-based composer Agustin Castilla-Avila and Spain-based composer Wladimir Rosinskij.

We “new-music” (“sound-art”?) composers are a community, and we form an informal global support system. We pool our resources, joke with our poet friends about which art form is more “non-profit,” and trust that we do somehow and significantly participate in what Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer called “The Tuning of the World.”

Have you ever thought about what the role of a contemporary composer in society might be?

I must admit that I have rarely let this topic concern me. When I feel the need to compose, I compose. From an existential perspective, even though my prime motive is to create the music I want to hear, I occasionally wonder if anyone else would want to, trusting that they just might. I don’t hope for that, but I welcome confirmation when I receive it.

In order to be free of external expectations and assumptions, I’ve never sought grant support or commissions, but happily consult with fine musicians about the practical aspects of clarity of expression and notation.

I remember the period of my life when I delved deeply into Jungian psychology, encouraged to do so by my mentor Dane Rudhyar. In our discussions, Rudhyar explained that Jung believed that artists, no matter how self-motivated, could not avoid reflecting the societal values in which they lived and created—what Jung referred to as the “collective unconscious.” Even an egomaniacal artist like Richard Wagner could not avoid representing the collective unconscious of his Germanic milieu. Conclusion: Not to worry; I must be doing the same.

Personally, I have no preference as to how my music is offered to the public—be it in a standard potpourri of era sampling, where the “modern” piece is programmed either at the beginning or right before intermission, followed by the Romantic crowd-pleaser, or on an “all new music” event.

Granted, the majority of living composers of “art” music adhere enough to historical models and vocabularies to still be considered as composers of “classical” music, thus subject to either a qualified acceptance by the mainstream “classical” audience or an outright rejection. In many cases, with the music of the avant-garde, the only true link with “classical” is the collaboration with “classically trained” musicians and a predominance of historically “classical” instruments.

Back in the late 1970s, when the neo-Romanticism backlash began to take hold, we looked for a term to describe what we were making, and for a while “sound art” (as a corollary to “visual art”) served us well, being suitably vague and un-classical. But then—leave it to the music industry—in the larger record stores, a “sound art” rack appeared, and any number of “Where should we put this album?” offerings accumulated.

I’m not interested in describing what I do in terms of what it is not, and I leave it to listeners to describe what they hear and how they respond and interpret. They have that right, after all, and they deserve to be considered as explorers, without the burden of stifling connoisseurship.

As a last thought, I suppose that it’s not the responsibility of composers to define or even understand contemporary music’s role and acceptance in society. I suppose that in a century of accumulation of available archived historical music, a century of declining consumption of music in the “live” concert setting, the growing reliance on miniature portable phone devices for art, entertainment, and just about everything else, the question of contemporary music’s role and acceptance appears to have become irrelevant. I’m okay with this scenario. I’m always heartened, however, when there are more people in the audience than on the stage.

As a poet yourself, where do you stand on the often-commented-upon relationship between music and poetry?

My first experience creatively was in writing poetry. The saved poems date from 16 or 17 years before I wrote my first music composition. I read poetry voraciously from an early age and managed to avoid the “dear diary” confessional genre in my early poems.

My first intersection of poetry and music came just a year after I began to compose and was catalyzed by the passing of my grandmother and my concurrent participation in a “concrete poetry” workshop with Mary Ellen Solt. I utilized three texts—one of my short poems, a melodramatic newspaper “in memoriam,” and a mathematical formula —all disassembled and then collaged, as a soprano solo, articulated through singing (the poem), Sprechstimme (the “in memoriam”), and low pitch intonation (the formula). The song is titled MeMarie, Marie being my grandmother.

Every subsequent music-poetry work has such a story, but I’ll proceed with merely listing the works:

(1) my own poetry: Lethe (1968, voice & piano); ERODOS (1973, for large chorus and percussion); Mute Hand Muse (2015, micro-opera); Passionate Geometries (2019, micro-opera); Heretic (1990–2023, micro-opera). My approach was to create a poetry-music dialog, rather than to “set the poem to music.”

(2) a hybrid of my poetry and something else: MeMarie (1970, micro- opera, adding the newspaper article and math formula); Through a Glass, Darkly (1986, micro-opera, adding a biblical quotation). My approach was to deliberately not to try to integrate the texts with the music or each other, with the musical material sometimes serving as a battleground for the ideas of the texts.

(3) texts from other poets: In the Dark Cycle (1969, chamber cantata; poem by Antonin Artaud); Labyrinths (1980/90, song cycle; poetry by W. S. Merwin); A Song Built from Fire (1984, micro-opera; poem by Jacint Verdaguer); A Measure of Love and Silence (2006, chamber cantata; poem by Tatiana Apraksina); A Sound-Shroud (2015, micro- opera; poem by Bill Knott); Breathless (2016, 30-minute cantata; poetry of Fakhruddin Iraqi, Sisupacala, Lao Tsu, Mechtild of Magdeburg, Quasmuna Bint Isma’il, Teresa of Avila, and Kabir.) My approach here was three-fold: first, showing the greatest respect for the work of the poets, then the determination to deliver the poetry in an inviting sonic environment, and finally to comment personally on the poetry as its images and ideas unfolded.

(4) aleatoric texts: ...as he seemed to appear to the beast in the distance... (1973, percussionist; text improvised by the performer); Colloquy in the Labyrinth (1969, 16 sounders, 4 dancers, and critic/conductor; a different text chosen by each sounder); Permutation Every 1934 (2021, aleatoric-text madrigal); Drunk Taken Pointed (2022, aleatoric-text madrigal).

These “madrigals” (for voices and instruments) are part of a projected cycle of five, entitled Flowers of Babel. I’m currently at work on the third madrigal, Ahura Mazda. In keeping with the cycle’s aleatoric orientation, I’m composing it in interchangeable modules, their order to be determined by a chance operation prior to performance.

The singers will at times function as instruments, exploring untraditional timbres, and the instrumentalists will at times endeavor to approximate vowel sounds and consonants. Some aleatoric word sequences, when spoken naturally, have a rhythm and accentuation arc identical to a song I know, and that song melody might thereby find its way into the madrigal, as an alternative to merely speaking the words.

This process, conceptually or in its sonic manifestation, could easily irritate the madrigal connoisseur or classical music lover, perhaps as being immature, irresponsible, or as “idle child’s play.” But there is the crux of it: composing as “play” rather than “work”—a “play of art” or “child’s play,” with all of its “What’s this?”, “What if I do this with it?”, “Would this fit?”, or “How far can I throw it?”. I’m reminded of the core idea of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, which leads us to the realization that, from innocence and through experience, we have the opportunity to reach a higher innocence. That’s my intent as I continue to create at this stage of my life.

What is some of the most memorable advice gleaned from your teachers that you in turn have passed on to your students?

One of my teaching responsibilities during my 24-year stint at SUNY- Purchase was to mentor music composition students—perhaps 50 or more over those years. My own training as a composer convinced me that, in a discipline like this, there can be no general syllabus, and no hierarchy of priorities. My mentors each offered something vital, however, thus forming the basis of my composition “teaching.” Here, then, as closely as I can remember:

- from Bernhard Heiden: “Sit before the manuscript paper for two hours a day, whether or not you can fill that time and space with creative work.” (He learned it while studying with Hindemith.)

- from Juan Orrego-Salas: “Young composers come up with too many ideas and have too little skill to explore and develop them. Imagine Rodin, standing before a block of stone, imagining what is within and then sculpting away what is not.”

- from Donald Erb: “Talent is not the most important factor. On Friday and Saturday nights, you’ll find the local bars full of talented people. Meanwhile, I’m home doing the work.”

- from John Eaton: “Young composers have a hard time structuring their musical ideas and often end up straight-jacketing them. It’s important to realize that form is a verb.”

- from Iannis Xenakis: “What essential branches of knowledge (maths, sciences, philosophy, psychology, etc.) have you explored? To be a whole composer, one must compose as a whole person.”

- from acting coach Harold Guskin (and apropos to music creation and performance as well): “What do you want to get with this line [or phrase, or musical idea]? Is that the best way to get it? Try it again.”

- from Dane Rudhyar: “Too many composers masquerade in an imagined creative persona, making it impossible for the music to be Truthful. The only way for your music to be truthful is to tell your own Truth.”

- from Noel Farrand: “If composing doesn’t bring you happiness or satisfaction, don’t compose. But it is an ideal form of masochism.”

- from Richard Cameron-Wolfe: “Which is more important to you: to compose (being there with that manuscript paper), or to be known as a composer (via custom sweatshirt text or tattoo)? I’m only a composer when I’m composing.”

During your years at Purchase, you were appointed the U.S. Director of the Center for Soviet/American Musical Exchange (CESAME). (By the way, does that rhyme with “Sesame” or is the “C” “hard’’? I can’t help but be reminded of Ali Baba’s “Open, Sesame!”.) You also fulfilled an administrative role at the Charles Ives Center in American Music. How did you become involved with these institutions?

In 1988, Soviet emigré pianist Efrem Briskin introduced me to the music of Leningrad composer Grigory Korchmar, and I was deeply impressed with his craft, imagination, and adventurousness. Shortly thereafter I invited Korchmar to SUNY-Purchase and the Leningrad Composers Union accepted the invitation on his behalf. Korchmar gave a wonderful lecture and performance of his music, and delivered a reciprocal invitation to me from the Union’s distinguished Chairman, Andrei Petrov. In 1989 I made the first of my many visits to Russia, where I lectured on American composers and attended a “profile” concert of my own music. Petrov proclaimed his desire to create an ongoing exchange program and together we created CESAME. [Petrov recognized the “Open Sesame” element of the acronym, as you did.] The following year I hosted the USA visit of Soviet composer Evgeny Irshai.

The Ives connection: In 1989 my composition Reconciliation was performed at the Ives Festival in Roxbury, Connecticut. There I met American composer Richard Moryl, director of the New Milford- based Charles Ives Center for American Music. We talked about CESAME, and he soon offered to host Soviet composers at his annual summer composer retreat, appointing me as associate director to facilitate the venture. In 1990 and again in 1991, we hosted the 10-day residency of five Soviet composers and a dozen Americans. Moryl was the next American composer to be invited to the USSR. Then, as you know, the Soviet Union collapsed, and CESAME ultimately had to be abandoned. But I continued to communicate with the friends and colleagues I had met there, arranging seven subsequent visits in the coming year, visits which took me to St. Petersburg, Moscow, Astrakhan, Nizhny Novgorod (formerly Gorky), and the Siberian cities of Novosibirsk, Omsk, and Krasnoyarsk. During each visit I presented scores and recordings of American music, and returned home with scores and recordings gifted to me.

Other doors began to open for me. From Azerbaijan, composer Faraj Karayev (son of Kara Karayev), whom I met in Moscow, invited me for two visits to Baku, as composer, lecturer, and pianist. A similar trip to Sofia, Bulgaria soon followed. Three times in the 1990s I participated in the Astrakhan Festival in southern Russia. Ukrainian composer Sergei Zhukov invited me to his annual Festival in Zhitomir, Ukraine in 2010, which began my ongoing relationship with Ukraine, including performances at the old Soviet Cosmonautics Museum in Zhitomir, where I performed Ukrainian and American piano music under a suspended Sputnik satellite! In Ukraine I met Kaspars Lielgalvis, director of the Latvian arts/cultural organization Totaldobze. He invited me to participate in the Riga “White Nights” Festival, and in 2012 I created a 90-minute multimedia work in an old factory with over 20 Latvian performers, titled Portal. It was the first of three such visits there. Ukraine became a vital “second home” for me, where I was able to collaborate with two modern dance companies and the new-music ensembles Sed Contra (Kyiv) and the Kharkiv Guitar Quartet. I developed a strong relationship with the Cxid Opera House (Kharkiv) and had the honor of presenting three of my micro- operas there, directed by Armen Kaloyan. On my last visit, just before COVID, Cxid Opera produced a concert entitled “Richard and Friends,” celebrating my kinship with and devotion to Ukraine and its culture.

Returning to Passionate Geometries, Telesthesia: 13 episodes/deliberations on multi-planar syzygy for cello quartet was written to memorialize a good friend and given a cryptic title that refers to a series of unusual “manifestations” after his death during which you “seemed to have seen him” in a variety of locations. Have you ever had similar experiences before or since?

Indeed I have, and the phenomenon of telesthesia (distance viewing) has manifested for me in two different ways: (1) inserting a memory (or vision) of someone or something into a real-time environment, as I often do with my dear departed friend Harold Geller; (2) “seeing” someone in their environment (at the time far from my own), as if teleported there, only to have that vision cross-fade with the environment in which I actually am.

Knowing of your involvement with Sufism, I first heard the opening flute solo of Kyrie (Mantra) IV as perhaps inspired by music for ney, the end-blown flute frequently heard in Dervish circles, but I’ve since learned that it was based on a Gregorian chant taught to you by your teacher Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan. Did you study music with him in addition to Sufism, as he belonged to the Chisti Order, long celebrated for its musicians?

I didn’t study music formally with Pir Vilayat, who was, incidentally, trained as a classical cellist, although the chanting of mantras (and Dervish dancing!) was always a part of our meetings and retreats. He directed me to the many Middle Eastern and North African flute traditions, emphasizing “the breath” and the “resonant breath” of one’s life-force, the singing voice. Yes, these musics have influenced how I compose for our “classical” flute, though not overtly.

By the way, I’ve recently learned that his father, Hazrat Inayat Khan, met and even taught Scriabin, and that his music was admired by Debussy.

His writings on music are among my “bibles” and are always in reach. Additionally, the music writings of Dane Rudhyar (including his The Rebirth of Hindu Music) have been a continuing influence on my relationship with music. I served as proofreader for his book The Magic of Tone and the Art of Music, published in 1982 by Shambhala (but regrettably in a drastically cut edition).

Hazrat Inayat Khan held an exalted view of music, believing that he who understands vibrations understands everything. Is this your belief as well?

I understand his concept, but I am not the exalted being that he was. My understanding of vibrations (shruti microtones, for example) is manifested, as honestly as I can manage, in my music. I can’t speak to how it may bring insight to other aspects of my life.

Passionate Geometries presents a retrospective of some of your work over the last 30 years or so. Has your style fluctuated over that span of time, or has it remained more or less consistent?

I don’t consider myself to have ever had a “style” for any period of time or sequence of compositions. I get an idea for a composition and then set about determining how to realize that idea. Not wishing to “repeat my successes (or failures),” I dismiss ideas that I’ve already addressed. Though I strive to let each composition get the style it deserves, listeners might perceive similarities which I had not consciously intended (or perhaps that I thought I had avoided). My dear sister Gayle Blankenburg, who has played all of my piano pieces (spanning 1982–2024) suggests that, amid a work’s complexity and unpredictability, “sooner or later, a really pretty phrase emerges”—and a highly personal one, I’m told.

Are you ever surprised by the direction a new work takes you?

Yes, but it happens thus: I’m not at my composing table, possibly not even in the midst of a composing period, and I get a flash of “what to do” next. There’s the surprise. Part of the reason is that (and many of my friends don’t believe me) when I’m not composing, I’m not a composer—and it often seems as though I’m not in control of when (or if) I’ll be one again.

From the liner notes for your Furious Artisans CD, An Inventory of Damaged Goods: