Guitarist Daniel Lippel releases a new version of Steve Reich’s iconic Electric Counterpoint. In collaboration with South African born ethnomusicologist Martin Scherzinger, Lippel approached the piece through the lens of its roots in Central Africa, specifically the traditional music of the Banda-Linda tribe, from which Reich borrowed material for the canonic theme of the opening movement.

| # | Audio | Title/Composer(s) | Performer(s) | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time | 14:48 | |||

| 01 | Electric Counterpoint: I. Fast | Electric Counterpoint: I. Fast | 6:53 | |

| 02 | Electric Counterpoint: II. Slow | Electric Counterpoint: II. Slow | 3:22 | |

| 03 | Electric Counterpoint: III. Fast | Electric Counterpoint: III. Fast | 4:33 | |

I have nursed an interest in recording my own version of Steve Reich’s Electric Counterpoint for several years. There are already many fantastic recordings of the piece available, including Pat Metheny’s iconic premiere version, and I have enjoyed listening to and learning from several of them. So my interest in doing my own version went unrealized for some time, mostly because I did not feel I had a perspective to contribute that would shed new light on the piece. Reich has found much inspiration in the music of Africa throughout his career. I found myself drawn to the idea that it would be interesting to explore the connections between Reich’s counterpoint pieces and the African music that partially inspired them.

Read MoreMy initial approach was largely based on some superficial characteristics I associated with certain African musical traditions. I felt that a version of Electric Counterpoint that emphasized metric duality (specifically the simultaneous rhythmic contextualization of a passage of music in both duple and triple meter), and timbral heterogeneity might begin to capture the spirit I was hoping for. Luck would have it that amidst the planning period for the recording sessions, my path crossed with South African born ethnomusicologist and composer Martin Scherzinger. Among his areas of scholarly and artistic interest is examining examples of how Western composers have integrated African musical material into their work. Martin was working on a paper on Reich’s Electric Counterpoint just at the time we met. He supported my feeling that metric duality and diverse timbres might begin to illuminate the African roots of the material. I learned from Martin about the original source for the canonic material from the opening movement of the work. It is taken from a traditional piece associated with adolescent initiation rites for large horn ensemble by the Banda-Linda peoples in Central Africa.

Martin’s paper details more of the background of this musical tradition and the link between Reich and European ethnomusicologist Simha Arom’s work on African traditional music. I will stick to how this information impacted the actual studio process and the final recording itself. Among the characteristics of performance practice in Banda-Linda horn ensembles is an embellishment technique of the main thematic material that involves subtly altering the theme, primarily through subtraction, so that the internal motives toggle between an emphasis of duple and ternary metric organization. With Martin’s guidance and Arom’s research, we made several alternate embellished versions of the main canonic material in all the guitar parts in Reich’s first movement, using the Banda-Linda practice as a model. Then later, in the editing process, I came up with a map delineating where the strict canon would be heard in each part, versus when an embellished “module” would enter and underscore a subtle shift to a ternary or duple feel. Based on the principles the musicology illuminated on the first movement, I applied similar parameters to the repeated cells in the third movement.

We also added several other elements to the studio process in the hopes of connecting the piece to its roots. A few of the guitar parts include preparations on the strings that suggest other plucked string instruments including the African lamellaphone, and lend a more percussive timbre to the texture. For the passages involving pulsating repeated block chords in individual parts, we divided the chords into three-note oscillating patterns to produce an internal ternary rhythmic grouping juxtaposed over the prevailing meter (for example, repeated C major block chords in one part became three layered divisi parts, each repeating a three note cell, C-E-G, the next E-G-C, and the last, G-C-E). For the repeated rhythmic cycle in the second movement (which Reich notates as a 3/4, 5/8, 4/4 repeated passage), I played multiple contrasting metric orientations in different parts, with a concluding “correction” to account for the nineteenth eighth note in the passage (for instance 6/8, 6/8, 7/8, or four 2/4 bars plus a 3/8). The intended result is a more linear texture that highlights the unique contour of this rhythmic cycle without internal mixed meter interruptions of the rhythmic feel.

My hope is that this unorthodox approach has generated a dynamic version that ebbs and flows as a live performance might and offers a fresh sonic take on the piece. Equally as important to me is that this version conveys reverence for both Reich’s original score and the traditional music culture he is referencing. It can be risky to claim to be drawing influence from an indigenous music culture not one’s own; we endeavored to do so with humility. Electric Counterpoint is a remarkable piece that touches on so many musical and cultural associations. My primary interest in creating this new version was to explore and experiment with the ways that its link with an African music tradition was integral to the spirit of the piece. As with any great piece of music, Reich’s Electric Counterpoint rewards many different interpretations, and this experience has only enhanced my appreciation and enthusiasm for the opportunity to hear the piece in familiar as well as new contexts.

I owe a great debt of gratitude to four individuals who worked closely on this project with me: Michael Caterisano who assembled the tracks with me in the initial stage of digital editing; Martin Scherzinger, whose expertise in African music and its intersection with Western composition helped to guide the production process; Memo Salazar, whose design captures the threads of geometry, community, and sonic diversity that I feel are such important aspects of this piece; and Ryan Streber of Oktaven Audio, who provided the ideal studio environment and virtuoso set of ears for the sessions, editing, mixing, and mastering of the final recording.

- Daniel Lippel, 11.2015

Recording engineer: Ryan Streber oktavenaudio.com

Digital editors: Michael Caterisano (http://www.michaelcaterisano.com/), Ryan Streber

Producers: Daniel Lippel, Ryan Streber

Musical supervision: Martin Scherzinger http://steinhardt.nyu.edu/faculty/Martin_Scherzinger

Design: Memo Salazar www.foolfactory.com

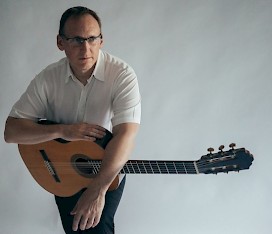

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

Guitarist Dan Lippel, called a "modern guitar polymath (Guitar Review)" and an "exciting soloist" (NY Times) is active as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist. He has been the guitarist for the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005 and new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. Recent performance highlights include recitals at Sinus Ton Festival (Germany), University of Texas at San Antonio, MOCA Cleveland, Center for New Music in San Francisco, and chamber performances at the Macau Music Festival (China), Sibelius Academy (Finland), Cologne's Acht Brücken Festival (Germany), and the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center. He has appeared as a guest with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and New York New Music Ensemble, among others, and recorded for Kairos, Bridge, Albany, Starkland, Centaur, and Fat Cat.

"Steve Reich's Electric Counterpoint for multiple electric guitars is surely one of the landmark modern works of its kind. Pat Metheny did a version in 1987 that came out as part of an album that included "Different Trains." That was a beautiful take on it but now we have another excellent one, multi-tracked by Daniel Lippel New Focus CD).

The piece as Reich conceived it was in part based on traditional Banda-Linda music of Central Africa. Lippel worked with NYU ethnomusicologist Martin Scherzinger to accentuate the African rootedness of the work. I must say the music sounds wonderfully well, perhaps the best it ever has in Daniel Lippel's hands. It is marvelously resounding and drivingly rhythmic. I am a huge Reich enthusiast and so it did not take any arm-twisting to hear this version. It is exceedingly beautiful to begin with, and even more so in this extraordinarily well articulated version. Keep in mind that this is an EP with around 15 minutes of music. A better 15 minutes I cannot imagine, unless it were to be on some other planet! All guitarists should hear this. Everyone else, too, while we are at it. Seminal." -- Grego Applegate Edwards, Gapplegate Music, 3.30.16

This second CD (New Focus fcr 165) is another aspect of crafting a legitimate new interpretation of a given piece of music. Guitarist Daniel Lippel goes back to some of the roots of Reich’s mature style, Ghanaian drumming. Reich seems to have achieved his personal artistic synthesis after his encounter and study with the master drummers of Ghana. It is here that he was finally able to synthesize the gifts received from his study of jazz (Reich was/is a jazz drummer) and his tape music experiments into the larger forms for which he is now known through these studies with West African musicians. And it is here that Lippel goes, with an assist from musicologist Martin Scherzinger, to create his (re)vision of this classic Reich composition.

Electric Counterpoint (1987) was written for and first recorded by the still wonderful jazz guitarist Pat Metheny. His recording is certainly definitive but, as with all music performance, hardly the last word. Several artists have presented their versions (David Tanenbaum’s acoustic guitar version deserves more attention by the way). It is a very appealing and interesting piece cast in a classic fast-slow-fast format that presents formidable challenges for the musician but not for the listener.

It is difficult (and certainly beyond the scope of this review) to say specifically what Mr. Lippel has done differently but there is clearly a difference (further notes can be found here). I am loathe to find adjectives to describe this recording except to say that it is well worth your time to hear it. It provides a different way of hearing much as Glenn Gould has done for Bach. Just sit back and enjoy. - Allan Cronin, New Music Buff, 4.3.2016

Along with his contributions (classical and acoustic guitars, electric bass, jaw harp) to Davis's On the Nature of Thingness, Dan Lippel has a new release of his own, specifically an EP-length treatment of Steve Reich's Electric Counterpoint. Tackling the piece comes with some built-in challenges: not only does the guitarist have to contend with the precedent-setting premiere performance by Pat Metheny, he/she must find a way to imprint his/her personality upon it despite some inherent constraints. In contrast to Riley's In C and Glass's Two Pages, both of which are amenable to different choices of instrumentation (Glass's includes “a single unison line of music [that] can be played by any combination of instruments”), Reich's piece is scored for a particular instrument and comes with specific tempo markings.

Fortuitously, Lippel, an ICE member since 2005, discovered that his own burgeoning interest in traditional folkloric music from Africa coincided with his desire to produce a version of Reich's piece. As those familiar with the composer's background already know, Reich traveled to Africa as a young man to learn about African drumming and ultimately incorporated what he learned into his own rapidly developing composing style. In short, the approach that Lippel proposed for his version, one that would emphasize metric duality (specifically a musical passage simultaneously executed in both double and triple meter) and timbral diversity would be a natural fit for the piece as opposed to a contrived one grafted onto it. Aided in this endeavour by South African-born ethnomusicologist and composer Martin Scherzinger (whose work also has appeared on New Focus Recordings), Lippel proceeded to map out various ways by which the African roots of Reich's composition might be brought into even sharper relief. From Scherzinger, the guitarist learned, for example, that the canonic material in Reich's opening movement draws from a traditional piece associated with adolescent initiation rites by the Banda-Linda, a Central African people who number about 30,000 and live in a wooded savanna region.

On timbral grounds, Lippel made adjustments to the guitar's strings to bring it closer in sound to plucked string instruments such as the African lamellaphone, an instrument comprised of iron rods. The balancing act here, of course, is that one must find a way to individuate the performance of Reich's work without altering it so radically that the character of the original is lost in the process. This is something Lippel does ultimately succeed in doing: the performance may sound superficially similar to Metheny's, but were one to listen to them side-by-side differences would become subtly audible, those of timbre especially. Don't worry: those massed guitars and spidery single-line patterns are still present, the middle movement still exudes the harp-like elegance we've come to know and love, and Reich's signature pulsation, bass and otherwise, remains firmly in place. But differences arise, too, a case in point the percussive-like fluttering that emerges midway through the opening part.

Anyone with a musicological bent will find much to appreciate about the notes by Lippel and Scherzinger that accompany the release. In their in-depth texts, the two enlighten the listener with information about the rhythmic approach of Lippel's version and the work's African connections (Scherzinger notes, for instance, that “a single instrumental line in Electric Counterpoint performs the pattern made by three distinct hocketing horns in the African ensemble”). Their analyses make clear just how sophisticated Reich's composition truly is. - Ron Schepper, textura, 5.2016

"Reich’s devotees have long known and celebrated the heritage of central African music that he explored—highly transformed—in many of his early works. Guitarist Daniel Lip- pel wanted to emphasize this African heritage in his performance of Electric Counterpoint, originally composed for Pat Metheny (M/A 1990) and recently recorded again in a fine performance by Jonny Greenwood (J/F 2015). Working with my old friend Martin Scher- zinger (a composer himself, and an important scholar who counts African music among his dizzying array of interests), Lippel experiment- ed with different sorts of timbres (including occasional preparation of guitars to resemble mbiras) and, now and then, a pronounced emphasis of the work’s metrical ambiguity to effect a sonic hybridity between Reich’s West- ern sensibility and an African one.

The result is stunning. The raspier timbres of the prepared guitars are quite effective in the outer movements, and Lippel’s artistry works on its own to give the central movement a welcome urgency that I’ve never heard before. Some of the timbres—particularly the phased chords shortly after the beginning of III, don’t have enough bite for me. Nevertheless, Lippel’s release reminds me—in a good way—of Glenn Gould’s famous dictum that the only reason to record a composition again is to do it differently."

- Rob Haskins, American Record Guide, Rob Haskins, July/August 2016

Daniel Lippel has released an EP on the New Focus Recordings label comprising a single work by Steve Reich: Electric Counterpoint (1987), also the title of the 15-minute EP. Lippel is co-founder and director of New Focus Recordings, and has served as resident guitarist of the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) since 2005, and of the new music quartet Flexible Music since 2003. He studied at Oberlin with Steven [sic] Aron, and with Jason Vieaux at the Cleveland Institute of Music.

In my recent review of Third Coast Percussion’s Steve Reich CD, I touched on the science of psychoacoustics, or the study of how the brain responds to sound and music. Reich often manipulates listeners’ perceptions of time through his repetitive, pulsing works, and Electric Counterpoint is no exception. It’s easy to become lost in Lippel’s playing; he jams his way through the three movements with impeccable rhythm and a verve that, while delightfully engaging, doesn’t emphasize any particular pattern in the music, instead washing over the listener in relaxing bursts of musical chatter.

There are 10 distinct parts in Electric Counterpoint — eight electric guitars and two electric basses. As in Reich’s other “Counterpoint” pieces (New York, Vermont, Cello), in live performances, either an ensemble will play together or a soloist will play one of the voices while the other nine are played on tape. Lippel, in the tradition of many guitarists before him, played and dubbed all 10 parts, giving each an individual flair and style. In his liner notes (available only online), he discusses his approach to the piece and how he strove to highlight the indigenous African influence that Reich has said pervades much of his own music. This approach involved highlighting differences in timbre in each of the parts and emphasizing competing meters or rhythmic structures. It’s a slightly different take on the piece, and it’s quite nice — a bit more dynamic than previous recordings.

The quality of sound also deserves mention. Ryan Streber of Oktaven audiO, a Juilliard-trained composer and audio engineer, mastered the recording. Martin Scherzinger’s expertise in African music informed Lippel’s interpretation, and Michael Caterisano, another Juilliard-trained composer as well as multi-instrumentalist and audio engineer, assisted in the early editing stages. It’s short. It’s available to listen to for free on the New Focus Recordings website. Check it out here. — Jeremy Reynolds, Cleveland Classical 1.3.2017

Is there an icon for contemporary electric guitar music? I really think so. That icon is Electric Counterpoint. There are a lot of fantastic editions, including the first one, played by Pat Metheny. Over the years this has become a true icon. What makes Daniel Lippel's version so interesting? He uses a very special perspective. Reich has found much inspiration in the music of Africa during his career. Lippel, on the other side, was attracted by the opportunity to explore the connections between Reich's pieces and the African music that inspired them.

“My initial approach was largely based on some superficial characteristics I associated with certain African musical traditions. I felt that a version of Electric Counterpoint that emphasized metric duality (specifically the simultaneous rhythmic contextualization of a passage of music in both duple and triple meter), and timbral heterogeneity might begin to capture the spirit I was hoping for. Luck would have it that amidst the planning period for the recording sessions, my path crossed with South African born ethnomusicologist and composer Martin Scherzinger. Among his areas of scholarly and artistic interest is examining examples of how Western composers have integrated African musical material into their work. Martin was working on a paper on Reich’s Electric Counterpoint just at the time we met. He supported my feeling that metric duality and diverse timbres might begin to illuminate the African roots of the material. I learned from Martin about the original source for the canonic material from the opening movement of the work. It is taken from a traditional piece associated with adolescent initiation rites for large horn ensemble by the Banda-Linda peoples in Central Africa.”

The meeting with the ethnologist and composer Martin Scherzinger allows him to deepen Electric Counterpoint's exotic roots and to work on new rhythmic cells:

“We also added several other elements to the studio process in the hopes of connecting the piece to its roots. A few of the guitar parts include preparations on the strings that suggest other plucked string instruments including the African lamellaphone, and lend a more percussive timbre to the texture. For the passages involving pulsating repeated block chords in individual parts, we divided the chords into three-note oscillating patterns to produce an internal ternary rhythmic grouping juxtaposed over the prevailing meter (for example, repeated C major block chords in one part became three layered divisi parts, each repeating a three note cell, C-E-G, the next E-G-C, and the last, G-C-E). For the repeated rhythmic cycle in the second movement (which Reich notates as a 3/4, 5/8, 4/4 repeated passage), I played multiple contrasting metric orientations in different parts, with a concluding “correction” to account for the nineteenth eighth note in the passage (for instance 6/8, 6/8, 7/8, or four 2/4 bars plus a 3/8). The intended result is a more linear texture that highlights the unique contour of this rhythmic cycle without internal mixed meter interruptions of the rhythmic feel.”

This unorthodox approach generated a new version, with greater dynamics flowing like a live performance and offering a new sound version of the piece. At the same time this version transmits reverence both for the original version and for the traditional musical culture to which it refers. It may be risky to claim to take influence from an indigenous musical culture that is not his own, but Lippel has managed to do it with great humility. Electric Counterpoint is a remarkable piece that touches and crosses so many musical and cultural connections. As in every great piece of music, Electric Counterpoint rewards many different interpretations, and this new interpretation has brought new enthusiasm, giving us the opportunity to listen to this piece in familiar and new contexts. Daniel Lippel treats Reich's sound as one of the materials of his art. Where art is a way to organize his considerations on history, on progress and on the relationships between these things and the single individual. The result is an irresistible combination of coldness and catchiness, time and counter-time.

-- Andrea Aguzzi, Neuguitars, 10.2018

Steve Reich isn’t exactly a miniaturist – his technical language rather precludes that – but, if there’s one concise piece that sums up his music in a satisfying, relatively thorough way, it’s probably Electric Counterpoint. A fifteen-minute-long work for solo guitar and pre-recorded tape, its three movements showcase Reich’s singular way with repeated motives, harmonic development, and structural drama.

Written in 1987 for Pat Metheny, Electric Counterpoint was initially recorded by him, as well. He’s proved a tough act to follow.

But guitarist Daniel Lippel’s one to give it a shot and, by and large, he’s got some compelling ideas about the pieces. On the whole, Lippel’s performance is similar to Metheny’s, at least as far as tempos are concerned. But in his approach to sonority it varies strikingly.

The mid-movement riffs of the first “Fast” section, for instance, are, in Lippel’s hands pointedly more aggressive than Metheny’s; his reading plays subtly but noticeably with distortion effects. Similarly, a focus on reverb draws out the hazy, meditative textures of the “Slow” movement. The finale combines elements of the previous movements, particularly an edgy tone and sometimes thick sonorities.

It’s an approach that’s welcome and works, at least to a point. One of the advantages of Metheny’s interpretation is the clarity between the music’s spare, inner parts and the bass lines that anchor the proceedings. That balance provides his reading with a strong sense of direction as well as allowing one to hear the fascinating interplay of Electric Counterpoint’s many moving lines. Lippel’s interpretation is cloudier and I, for one, missed some of the interaction of the lines present in the older account.

At the same time, though, Lippel manages to draw out the music’s lyric qualities nicely: his is a performance that truly sings. It also doesn’t lack for energy or warmth. And, at the end of the day, surely there’s room for more than one interpretation of this brilliant piece on your shelf.

— Jonathan Blumhofer, The Arts Fuse, June 2019